On January 19, 2026, the Potomac Interceptor, a major sewer pipeline, collapsed along Clara Barton Parkway in Montgomery County, Maryland. The pipeline runs through the C&O Canal National Historical Park near the Potomac River, and the collapse caused the significant overflow of 200-300 million gallons of untreated wastewater into the Potomac River.

Crews installed emergency bypass and flow-control measures to reduce and ultimately contain the overflow while the longer-term repairs are planned alongside federal, state, and local agencies. The incident brought increasing attention to the condition of aging infrastructure that carries wastewater beneath our communities every day. It also raises scary questions about the consequences that occur when those systems fail.

The Potomac Interceptor’s collapse functions as an important symbol. It represents the risk that communities across the country face on a daily basis as they rely on wastewater systems that were built decades ago and which now exceed the amount of time they were intended to function. These systems break down, and the impacts go far beyond utilities and ratepayers. The failures can threaten water quality and harm river ecosystems. They require costly emergency responses that take resources away from long-term solutions.

The scale of the challenge is national. The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency’s Clean Watersheds Needs Survey is the federal government’s comprehensive assessment of wastewater and stormwater infrastructure needs. It notes that about $630 billion will be required over the next 20 years simply to maintain and modernize publicly owned wastewater treatment works and other clean water infrastructure across our nation. This figure shows how much investment is truly needed to repair these aging systems and meet water quality goals in order to protect rivers and downstream communities. Infrastructure failures will continue to occur without sustained funding, and with them will be real consequences for public health and the environment.

What Are State Revolving Funds?

State Revolving Funds (SRFs) are one of the best and most important tools at cities’ disposal to solve this need for better infrastructure. The Clean Water State Revolving Fund and the Drinking Water State Revolving Fund are long-standing federal–state partnerships that provide affordable financing to communities for water infrastructure projects. SRFs support investments in wastewater treatment and stormwater management. They also aid projects that protect drinking water supplies. These programs allow states to tailor investments to local needs, which can mean anything from upgrading treatment plants to improving stormwater systems to restoring natural features that support water quality.

SRFs are designed to let public dollars stretch over time because, as loans are repaid, the money goes back into the fund and can be used again to support new projects. SRFs are a proven tool that empowers states to address community water needs and support job creation and long-term economic benefits tied to infrastructure investment.

Why SRFs Work for Rivers and Communities

SRF investments help prevent failures in these systems — like what happened on the Potomac — because they enable communities to upgrade infrastructure before it reaches a breaking point. SRFs play an important role in cutting down pollution and improving water quality while supporting resilient water systems. SRFs can fund nature-based infrastructure such as wetlands and floodplains, and some recent policy proposals call for dedicating a significant share of SRF capitalization to these projects because of their flood-risk and water-quality benefits. They are an incredible tool to deliver co-benefits for people and rivers.

These approaches are especially valuable as communities face increasing pressure from extreme weather and changing hydrologic conditions. Investing in solutions that work with natural processes, SRF-funded projects can strengthen resilience while protecting drinking water sources and downstream ecosystems.

Why This Moment Matters

The Potomac Interceptor collapse offers a clear illustration of what happens when aging systems are pushed beyond their time limits. Emergency repairs and temporary fixes are costly, and they are disruptive. This clean-up is far less effective and more expensive than proactive investment. At the same time, the EPA’s national assessment shows that infrastructure needs are widespread and substantial. These realities point to a simple conclusion that continuing to defer investment will only increase risks and costs over time.

The nation’s documented clean water infrastructure needs are roughly seven times greater than current annual federal investment levels. While the State Revolving Funds (SRF) are currently authorized up $3-4 billion per year, American Rivers estimates that at least $10 billion annually is needed to adequately address wastewater and stormwater infrastructure demands.

People across the country depend on functioning wastewater systems every day, even though many rarely think about them. The failure of these wastewater systems can contaminate rivers and impact recreational waters, causing communities to face significant environmental and financial consequences. Investing in water infrastructure is therefore a choice to dedicate funds for the protection of public and river health, as well as community resilience.

A Call to Action for Congress

Investing in State Revolving Funds is one of the most direct ways Congress can help communities modernize wastewater systems and protect rivers. State Revolving Funds work, but their impact depends on strong federal leadership. It is key to reauthorize and strengthen SRFs through increased federal investment and streamlined access for small and disadvantaged communities. In addition, there must be dedicated funding to natural infrastructure and modernization of permitting and project delivery. These reforms would help ensure that SRFs are equipped to meet today’s infrastructure challenges and support solutions that protect both people and rivers.

The infrastructure needs identified by EPA and the visible consequences of water system failures like the Potomac Interceptor collapse show that this is not a problem Congress can afford to ignore. We know how to fix the problem. What is needed now is the political will to scale to match the magnitude of the challenge.

As Congress considers a water infrastructure package, American Rivers will urge Members of Congress to enact SRF reforms to fix our pipes, modernize water systems, and protect rivers.

You can join us by taking action now.

In 2023 and 2024, the Washington State Legislature acted with clear foresight, directing state agencies to evaluate options for maintaining water, energy, recreation, and transportation services in the absence of the four lower Snake River dams.

With the dams’ future long the subject of debate, investing in these studies is prudent. It means the Northwest will be informed and ready to adapt with resilient alternatives should Congress decide the dams must be removed.

That remains a possibility, one that would honor tribal treaties, help restore the once-great salmon runs of the Snake River basin, and prevent the extinction of our region’s endangered Southern Resident orcas.

The four studies are underway, and they already show viable alternatives for continuing the services the lower Snake dams currently provide. Let’s begin with transportation. It turns out that ending barge portage of wheat, fertilizer, and some wood products along the lower Snake River could have surprising benefits.

A recent analysis by the Washington State Department of Transportation (WSDOT) shows that shifting from barge to rail would reduce how far trucks have to travel from farms to rail terminals or river ports by about 18 million miles every year. That reduction would lower annual emissions by approximately 29,000 metric tons of carbon dioxide equivalent. Cleaner air and less road wear and tear are some of the other obvious benefits.

How much would this change cost? The same WSDOT analysis shows a total annual increase of $8 million to farming enterprises. Farm support to offset this amount would be justified, considering taxpayers are projected to spend $4.5 billion to $8.35 billion over the next 50 years to keep the four dams, and this eye-popping expenditure would no longer be needed.

The study by WSDOT is progressing on schedule, with a final report due to the legislature by this December.

On water supply, we know the reservoir behind Ice Harbor Dam irrigates up to 55,000 acres of farmland, and Lewiston and Clarkston use the reservoir behind Lower Granite Dam for municipal water. In their draft study last year, the Washington Department of Ecology and the Bureau of Reclamation found there will be more than enough water in a free-flowing lower Snake River to cover these needs. Ecology is expected to release the final study by early summer.

The Washington State Recreation and Conservation Office and the Department of Fish and Wildlife are expected to analyze the business opportunities for recreational activities on 140 miles of free-flowing river. The possibilities here are exciting and endless, including increased fishing and the potential to create the state’s only multi-day rafting experience. The proposed study would generate hard economic numbers on the significant recreation jobs and revenue that would result for our local and regional economy. Globally, nature-based tourism generates more than $600 billion a year, and Washington’s unique river and mountain ecosystems offer us the chance to bite into a bigger slice of this pie.

Finally, we want to address the state study into the hydropower the four lower Snake dams produce. Pacific Northwest National Laboratory (PNNL) completed phase one of this study last year. It determined that the dams produce an average of 700 megawatts each year, far less than is usually stated. Water availability, grid constraints, and ensuring critical fish passage impact the dams’ energy production, which is less than 4% of the Northwest’s total average power generation.

The PNNL report shows the lower Snake River dams are not designed to significantly increase output when it’s most needed, particularly during extreme weather events. Further, their role is overshadowed by upriver federal storage dams. It also found that because the lower Snake dams are dependent on seasonal stream flows, their future contributions will likely be reduced as the region trends toward less snowpack.

PNNL acknowledged the local grid support that the dams provide to the Tri-Cities. Other national studies show that strategically placed battery storage can provide the fastest reactive power for communities and grid support. Governor Bob Ferguson has asked that the full energy study be completed by 2027.

These state studies are not authorized to decide the fate of the dams on the lower Snake River. Their power and purpose rest in preparing all of us for such an eventuality. American Rivers is grateful they are happening, so communities are ready, and so the intertwined environment and economy all life depends upon in the Northwest can continue to thrive into the future.

This blog was first published in the Tri-City Herald, Feb. 22, 2026 https://www.tri-cityherald.com/opinion/opn-columns-blogs/article314580320.html

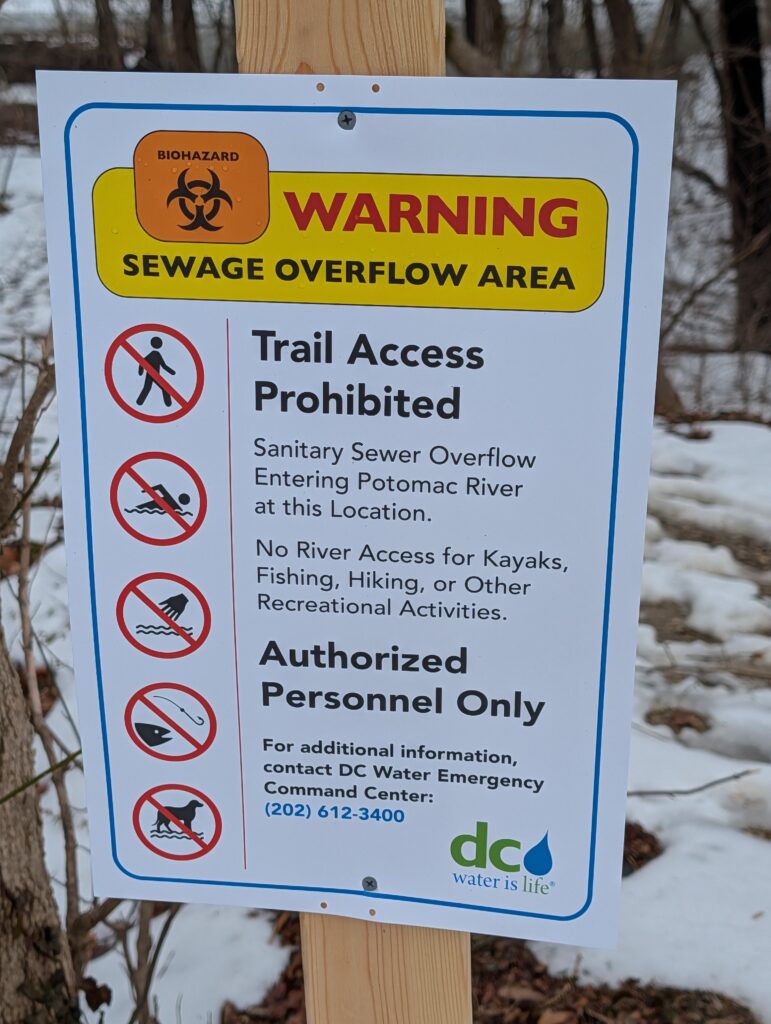

I recently visited the site of the Potomac River Sewer Spill — what is now likely one of the largest accidental sewage spills in U.S. history. Given the ice and snow still on the ground, it was a challenge to get to, but I immediately knew I was going in the right direction because the smell kept getting stronger.

I bumped into someone that lives nearby who was also walking to inspect the damage. When we finally arrived at the site, we were both a little taken aback by how much equipment was there. Several massive pumps are taking raw sewage out above the breach in the Potomac Interceptor pipe — a massive 72-inch concrete pipe — and putting it into the C&O Canal, which runs parallel to the river. From there the sewage flows down about a quarter of a mile before it is re-routed back into the undamaged portion of the interceptor pipe.

It’s funny how sewage doesn’t look like you might think — rather than a brown sludge, it’s very gray colored water. This is due to the quantity of water going down our drains, which washes everything through the pipes. However, you can tell this is definitely sewage both by smell, and the amount of toilet paper and “flushable” wipes you see getting caught up on sticks and branches in the canal. These wipes aren’t actually flushable and can wreak havoc on our rivers and water infrastructure even when there’s not an emergency. This was the driving motivation behind the introduction of the WIPPES Act in Congress last year.

Normally, the pipe transfers roughly 40 million gallons of sewage every day. When the pipe failed on January 19, massive amounts of sewage poured into the canal, which then overflowed, sending sewage into the Potomac River. Over the course of 10 days, before the site was contained, it’s estimated between 200 to 300 million gallons of sewage ended up in the river. That’s like filling every bathtub in the nation’s capital with sewage, many times over, and then letting it all run into the river.

Fortunately, according to D.C. Water, drinking water supplies were not impacted, but the spill caused health advisories and urgent warnings to avoid contact with the water in both the river and the Canal. While necessary, this is a disappointing development as the Potomac is widely used for recreation — be it kayaking, rowing, rafting or boating.

Our partners, Potomac Riverkeeper Network, have been tirelessly collecting data and finding that in the midst of the overflow, bacteria levels in that stretch of the river skyrocketed to over 4000 times the safe recreational level. It’s too early to say what the long-term impact on the Potomac will be — some sewage was frozen during the recent cold weather, and as that melts we could see bacteria levels spike again. It’s also possible that other pollutants commonly found in sewage — forever chemicals, pharmaceuticals, etc — will end up settling into river sediment, killing or poisoning the fish, birds and insects that live in those stretches of the river.

If you live in this area as I do, the C&O canal area is a popular spot to walk, bike, and access the river for fishing and boating. It’s part of the National Park System. We have been taking our kids there ever since they were toddlers. I can still picture my daughter giggling at the sight of a Blue Heron grabbing a fish there. While the sewage overflow is no longer flowing into the river (for now), the historic canal is being used as a bypass for the sewage. There is a literal river of sewage flowing open along the towpath that parallels the canal. The estimated repair time is going to be 9-10 months, disrupting the communities nearby. This doesn’t include time for the environmental remediation (removing contaminated soil, etc.) that will have to be done on the area afterwards.

The most frustrating thing about all of this is how preventable it all was. That sewer line was built in the early 60’s and it was already known to be past the end of it’s service life. That’s why D.C. Water was in the process of replacing parts of it; ironically the section that failed was due to be replaced this spring. If only we had invested in repairs a couple of years ago.

And that’s the rub — this is a problem for the entire country — we don’t invest enough in sewer infrastructure repairs. Instead we tend to react crisis by crisis, instead of being proactive. The American Society of Civil Engineer’s Bridging the Gap report states that over the next 20 years, we will have a $270 billion funding gap for sewer system repairs and a $176 billion gap for stormwater systems.

None of these sewer system collapses are inevitable — we have the technology and the know-how to understand where repairs are needed and when. Most of the problem is the lack of funding and political will. Which sadly means, unless we get our act together, there will be more of these spills in our future.

In May of 2023, the Supreme Court handed down a decision that significantly limited the scope of the Clean Water Act, undoing protections that safeguarded the nation’s waters for over 50 years. Specifically, it erased critical protections for tens of millions of acres of wetlands, threatening the clean drinking water sources for millions of Americans.

While the Biden administration amended rules to comply with the Supreme Court ruling, the Trump administration recently released a new draft rule that would go further than even the Supreme Court in limiting what waters can be protected.

The Clean Water Act’s definition of “Waters of the United States” (WOTUS) is core to defining what waters are protected and which aren’t. Unfortunately, the Trump Administration’s newly proposed WOTUS rule would roll back protections for vast areas of wetlands and river tributaries. It’s estimated that close to 80% of America’s remaining wetlands would lose Clean Water Act protections. As written, the rule would leave many waterways vulnerable to pollution, degradation, and destruction, threatening water quality and community resilience across the country.

Here are our top four concerns with the new WOTUS proposal

1. The rule requires streams and wetlands to have surface water “at least during the wet season” in order to qualify for protection. But it never defines what the wet season actually is.

What this means for rivers: Wet seasons vary dramatically from region to region, and without a clear, science-based definition, many healthy and ecologically important streams risk being excluded.

2. Narrow definitions and expanded exemptions shrink the scope of protected waters.

What this means for rivers: By redefining “tributary” to include only streams with year-round or steady “wet-season” flow, and expanding exemptions for wastewater and waste-treatment systems, the new rule would eliminate protections for many intermittent streams and man-made infrastructure that function like natural streams, opening the door to more unregulated pollution. Many rivers in the Southwest only flow for part of the year. This updated definition would put many of these rivers at risk.

3. The rule suggests any artificial or natural break in flow cuts off upstream protection.

What this means for rivers: Under the proposed rule, a culvert, pipe, stormwater channel, or short dry stretch can sever jurisdiction. This means upstream waters that feed larger rivers may no longer be protected, allowing pollution to still flow into nominally protected rivers and streams.

4. The rule significantly eliminates wetland protections by requiring “wetlands” to physically touch a protected water and maintain surface water through the wet season.

What this means for rivers: The new definition excludes many wetlands, which naturally store floodwater, filter pollutants, and safeguard communities. This puts the drinking water for millions at risk and increases the risks of flooding for many communities.

The health of our rivers depends on the small streams and wetlands that feed them. By discarding science, narrowing long‑standing definitions, and creating confusing jurisdictional tests, the Trump Administration’s proposed WOTUS rule risks undoing decades of progress toward cleaner, safer water. America’s rivers—and the communities that depend on them—deserve better.

These rollbacks will put our waterways and the life that depends on them in jeopardy. The public comment period to speak up and defend clean water protections is open until January 5. Please take action today and send a letter to the EPA urging them to keep the current definition of Waters of the United States in place!

We are once again heading into a government shutdown, which is paralyzing Washington, D.C. The last shutdown stretched a record 35 days in 2018–2019—and whether this one is brief, partial, or prolonged, the damage will be real.

A shutdown is not just a Washington problem. It directly threatens our river economy, undermining the clean water, healthy ecosystems, and infrastructure that local businesses and communities rely on. From commercial navigation and fishing to recreation and tourism, shutdown disruptions ripple downstream, hitting small businesses, workers, and families across the country.

Anticipated Impacts on the River Economy and Beyond

Environmental Protection Agency (EPA)

- Halts cleanups and inspections at Superfund sites along rivers and watersheds.

- Suspends routine inspections of drinking water systems and hazardous waste facilities, raising risks for communities and industries downstream.

- Pauses State Revolving Fund (SRF) programs for clean and drinking water, as well as brownfield grants critical to riverfront redevelopment.

- Delays Clean Water Act permits and compliance plans, stalling infrastructure projects and private-sector investments, including shutting down laboratories that test water quality samples, undermining timely detection of pollution.

National Park Service (NPS)

- Closes or cuts staffing at national parks and historic sites that anchor river-based tourism economies.

- Shuts down visitor centers, restrooms, and trash collection, leaving river recreation areas unsafe and unwelcoming.

- Delays maintenance on river trails, roads, bridges, and facilities, raising risks of damage or accidents.

- Curtails search-and-rescue and wildfire mitigation in river-adjacent lands.

U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (USFWS)

- Furloughs most non-emergency staff, stalling habitat restoration and riverbank stabilization projects.

- Halts Endangered Species Act consultations and permitting reviews, creating regulatory limbo that hurts both conservation and development planning.

- Suspends wildlife monitoring and refuge management along river corridors.

National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA)

- Suspends coastal and riverine resilience grants, marine debris removal, and estuary water quality monitoring.

- Slows or stops monitoring of harmful algal blooms- critical for drinking water safety and fisheries health.

- Reduces fisheries management and enforcement capacity, hurting river-dependent fishing communities.

- Delays research and mapping that support states and local governments in planning for flood resilience and economic development.

Congress can Keep Government Open and Deliver a Bipartisan Solution

A shutdown doesn’t just freeze time in Washington – it weakens and paralyzes our ability to protect rivers, support clean water, and grow the river economy, which employs hunters, anglers, engineers, construction workers, outfitters, guides, dam operators, and small business owners. Congress must act together to keep the government open and protect the resources and communities that depend on a fully funded and open government.

Urge Congress to protect our rivers and communities.

One year ago today, Helene devastated my southern Appalachian home and the surrounding communities. The storm touched river valleys and communities from East Tennessee to western North Carolina, upstate South Carolina to Georgia, and beyond.

We lost valued community members.

We lost access to natural spaces we relied on for recharge and connection.

The rivers we loved for fishing, paddling, and sustaining local businesses were left clogged with trash and debris.

Infrastructure like roads, bridges, and dams failed — leaving disconnection and communities at risk.

When I think back to those early days, I remember hearing the same question again and again: “Where can I help?” And the answer was simple, help your neighbors. We formed flush brigades (without running water we hauled non-potable water for flushing toilets), filled each other’s drinking water jugs, and shared hot drinks in my driveway as we organized to make sure that everyone had what they needed most.

Of course, restoring rivers is also my job. In order to be most helpful, I knew we needed to work together with local partners — who in many cases were my neighbors. With MountainTrue and Riverlink we listed the Rivers of Southern Appalachia on America’s Most Endangered Rivers® list to call for the resources we need to recover. Our advocacy centered on making rivers and communities safer — by addressing high-risk dams, removing storm debris, rebuilding stronger water infrastructure, supporting voluntary floodplain buyouts, and ensuring access to federal recovery funds.

The progress of the past year has been grounded in one clear goal: not just to repair rivers, but to make them more resilient for the future. One major win came through House Bill 1012 that created the new North Carolina Dam Safety Grant Fund with $10 million dedicated to addressing high-hazard dams damaged by Helene. Additional resources flowed to MountainTrue to support storm debris cleanup which created jobs and ensured ongoing reciprocity for our rivers. Another silver lining was when we brought the community together to celebrate at New Belgium Brewing to toast our hard work and take action for the work that’s ahead.

Recovery doesn’t end when the debris is cleared or when the funding comes through for the dam removal. True resilience means preparing for the future knowing that the next storm is on the horizon, focusing on advocacy efforts that will help long term.

America’s Most Endangered Rivers® calls on communities to spotlight the rivers at a crossroads, where decisions in the next year will shape their future for decades. Nominations are open now and it is a powerful way to keep community safety at the forefront of public attention.

As I mark this anniversary, I feel deep gratitude for the rivers that keep flowing, for the partners who stood shoulder to shoulder in recovery, and for the colleagues who continued to inspire me with their commitment and care. Helene reminded me that resilience is both a collective and personal journey. As we look ahead, I carry the resolve that we can and must build a future where rivers — and the people who depend on them — are ready not just to survive the next storm but to thrive in its aftermath.

What do you learn watching a river for fifteen years?

Do you notice little changes along with big ones? Do the animals tell a story? Does the water share its secrets?

How does public funding investment help to restore rivers?

American Rivers has been working with a group of experts along the Patapsco River in Maryland for more than a decade to answer these very questions. It has been a monumental group effort to document the river’s response to dam removal in terms of changes to biology and physical structure.

The process of monitoring the Patapsco River started back in 2009 before the Union and Simkins dams were removed (2010 and 2011) and continued through the removal of Bloede Dam in 2018. Monitoring the river was required by regulators for five years following completion of each project to track any changes to the river and its aquatic communities.

The main goals of these dam removal projects were to:

- Reconnect historic migration routes for fish species moving between saltwater and freshwater

- Provide access to upstream spawning and rearing habitat for migratory and resident aquatic species

- Eliminate a documented public safety hazard and attractive nuisance

Monitoring the river allowed us to figure out if our projects goals were met and to ensure nothing crazy happened as a result of the dam removals.

We considered questions like— what will happen to the native fish if we remove these dams? Will migratory fish be able to access spawning habitat upstream? Will the tiny critters known as benthic macroinvertebrates (essentially, water bugs) experience any changes as a result of habitat alterations?

We also considered what would happen to sediment and water flow if these dams were removed. We contemplated questions like— how fast will the sediment leave the former impoundments and move downstream? Where will the sediment go and what will be left behind? Aquatic animals live in and on the sediment, and they may look for certain sediments for spawning, so these queries impact them as well.

I am happy to share that through the extensive monitoring effort, American Rivers and our partners have determined that the objectives of this dam removal project were achieved.

American Rivers has compiled our Patapsco River Restoration Project Research into one easy to access page: https://www.americanrivers.org/patapsco-river-restoration-project-research/. This page illustrates the depth and breadth of the vast amount of knowledge that was gained from this publicly funded effort. We plan to continue updating the site as more data and articles are published.

Key Takeaways

Biological Monitoring

- Some species of migrating fish, including alewife and blueback herring, are making their way above the former Bloede Dam and spawning. MBSS even noted that nine species known previously to only be observed downstream of the Bloede Dam were observed upstream.

- Egg/larvae sampling results further verified that blueback herring actively spawned in the restored reach above Bloede Dam in 2024.

- Both alewife and blueback herring environmental DNA (eDNA— these are little bits of genetic material that living things leave behind in the water) was detected at sites upstream of Bloede Dam after the dam’s removal, but not before.

- American eel spread out once the Bloede Dam was removed and were climbing the eel ladder at Daniels Dam in droves.

- Benthic macroinvertebrates and resident fish seemed to recover fairly quickly after the completion of the project.

Physical Monitoring

- The physical (or geomorphic) changes to the river followed what was predicted by researchers based on site-specific modeling and monitoring results at other dam removal sites.

- The vast majority of sediment within the Bloede Dam impoundment evacuated within the first year post-removal.

- The sediment was observed moving downstream relatively quickly and causing no significant problems downstream. The river came to resemble a more natural system once again.

If you would like to dig a bit deeper into the findings of the monitoring efforts (but maybe don’t have time to read the full reports), check out this page.

What Happens Now

It’s important, especially in cases of such a significant investment of effort and public funds, to share these results with the broader community of researchers, practitioners, and regulators. Consequently, American Rivers and our partners have been presenting on this project at conferences and other events. We will be sharing a series of conversations on this project with our National Dam Removal Community of Practice in June. You can register here.

Our partners at MBSS are working on a collection of articles for publication exploring the response of different species to the removal of the dams. Our partners at USGS are working on their second publication highlighting the sediment response to the Bloede Dam removal. A series of other publications have already been produced and can be found here. As more publications come out, we will post them to that page.

In addition, we are now talking with Maryland DNR and the broader community surrounding Patapsco Valley State Park about potentially removing the upstream Daniels Dam. Those conversations will be ongoing this year as we work through a feasibility study and community engagement process. We offer an abundance of gratitude to our funders at the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) and the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (USFWS) for supporting this long-term monitoring project. Public investment in river restoration is critical to ensuring that healthy rivers are supported for the benefit of all.

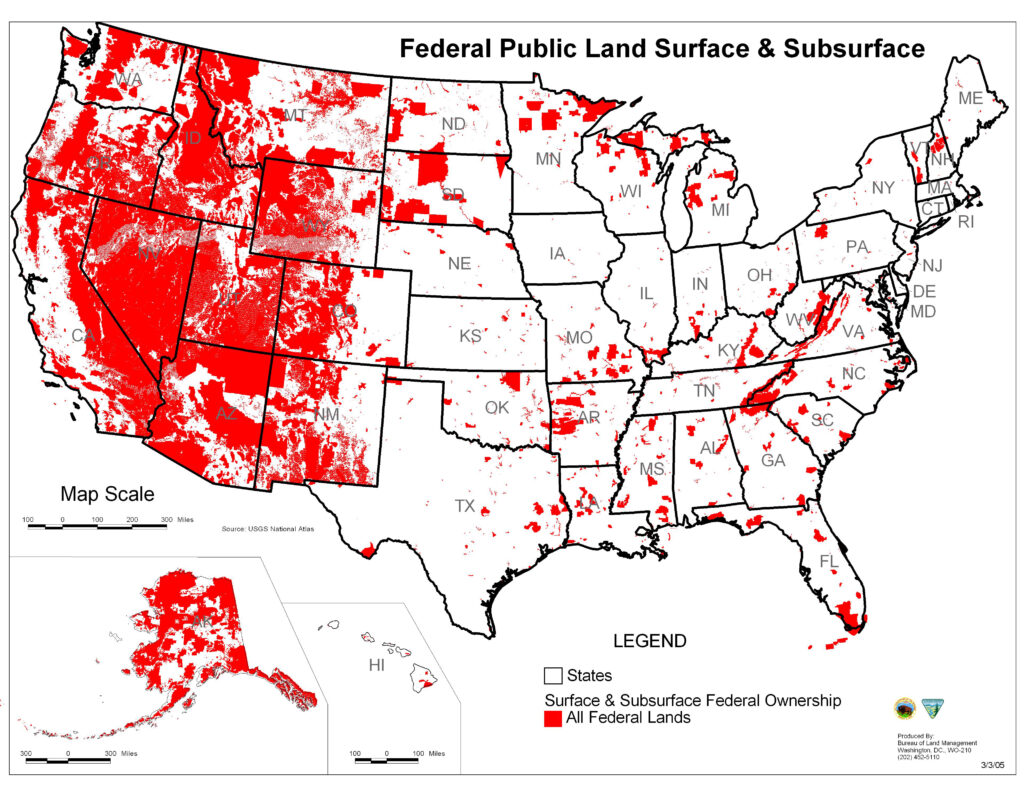

It’s hard to overstate the relationship between federally owned public lands and clean drinking water in the United States.

For some 180 million Americans, the water in our faucets began many miles away in a stream or river, flowing for miles through a public forest or grassland, where rain and melting snow were absorbed, stored, filtered, and cooled to nature’s perfection.

Public lands comprise 640 million acres, or about 28 percent of the nation’s landmass. They include national parks and preserves, national wildlife refuges and conservation areas, national monuments and wilderness areas. These lands provide a disproportionately high amount of the nation’s clean drinking water supply to downstream communities—and the connection is especially strong in the West.

A 2022 study by the U.S. Forest Service revealed national forests in the West comprised 19.2 percent of the total land area yet contributed 46.3 percent of the surface water supply. In the East, national forests comprised 2.8 percent of total land and 3.8 percent of the water supply.

Federal public lands supply clean drinking water to over 2.9M people living in Oregon

Take the city of Portland, Oregon, for example. The Forest Service owns about 94 percent of the Bull Run Watershed, which sits 25 miles east of the city and supplies 90 percent of its drinking water. In fact, recent data shows more than 2.9 million Oregonians receive their drinking water thanks to federal public lands.

Protected public lands and the intertwined watersheds they support is something all Americans deserve.

“Public lands are key to what we care about most—rivers that are filled with clean, free-flowing water to sustain people, fish, farms, and wildlife,” said Sarah Dyrdahl, Northwest regional director for American Rivers. “These lands and the rivers they support are the lifeblood of our local communities and economies.”

Historically and even now, lawmakers have proposed selling off federal public lands. It’s expected this would lead to increased clear-cutting and other extractive activities that could create pollution, reduce water quality, and ultimately increase water treatment costs. Human-caused destruction of rivers has already devastated nature and put our health at risk.

The bottom line is that what happens on the public’s land also happens to the public’s water, as discussed in our previous blog, “The Secret Double Life of America’s Public Lands.” And the public in the West and nationwide overwhelmingly supports clean water protections and conservation of our priceless public lands.

It’s essential we keep public lands in public hands, to safeguard our rivers and our nation’s water security.

2024 was a fantastic year for dam removals in the Mid-Atlantic region. Out of the 108 dams removed across the country, 39 (or 36%) came from the Mid-Atlantic region. What a powerhouse!

Did you know that American Rivers has three staff currently managing and providing technical assistance on dam removal projects in the Mid-Atlantic? Lisa Hollingsworth-Segedy is our resident dam buster, having been involved in more than 100 dam removals! Lisa works mostly in western Pennsylvania and the Ohio River Basin.

Jessie Thomas-Blate (that’s me!) works in eastern Pennsylvania, Maryland, Virginia, and recently dabbles in New Jersey. Jessie also co-leads the Virginia Stream Barrier Removal Task Force, which is a community of practice focused on increasing collaboration amongst professionals working on various aspects of dam removal and road stream crossing projects. We have a similar community of practice in Pennsylvania that Lisa and Jessie help co-lead called the Pennsylvania Aquatic Connectivity Team. In fact, many states have these collaborative groups working to advance river restoration in a more coordinated way.

Newer to our team is Corinne Griffith-Butler who is supporting projects in Pennsylvania and Maryland. Corinne will be helping a lot with outreach in Maryland and helping to knock down the queue of waiting projects in Pennsylvania.

Here is the breakdown of dam removals in Mid-Atlantic states:

- Maryland: 1

- New Jersey: 2

- Ohio: 2

- Pennsylvania: 27

- Virginia: 7

Virginia

On Rock Island Creek (a James River tributary) the six-foot high Baber Mill Dam was removed after nearly 200 years. This was an important project to support the proliferation of the endangered James spinymussel by reconnecting 45 upstream river miles of habitat. Many freshwater mussels rely on species such as American eel and sea lamprey to move around in river systems. The forestry management company Weyerhaeuser worked with Virginia Department of Wildlife Resources to help restore this river.

Just slightly farther north, the long-awaited Ashland Mill Dam (13 feet high) was removed on the South Anna River in Ashland, Virginia. Davey Mitigation, a private ecological restoration firm, completed this high priority project in pursuit of mitigation credits; credits issued by the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers and the Virginia Department of Environmental Quality that are sold to developers to offset environmental impacts of future projects in the York River watershed. This is the first time a dam removal project of this type has been implemented in Virginia using this business model, which offers a way to protect the environment at no cost to taxpayers. The dam’s removal will give access to at least seven species of fish, including American shad, that are currently blocked from accessing hundreds of miles of historical spawning and rearing habitat above the dam.

Ohio

The tallest dam removed in the Mid-Atlantic in 2024 was Timber Lake Liberty Dam (34 feet tall) on a tributary to the Olentangy River in Delaware County, Ohio.

The Warren Water Works Summit Street Dam (10 feet high) was removed as part of a large, regional effort to remove low head dams and restore water quality and habitat within the Mahoning River. Additional dam removal projects are in various stages of planning for removal upstream and downstream of the Summit Street Dam, which altogether will result in nearly 35 miles of free-flowing Mahoning River. As more of these dams and their accompanying sediments are removed, the recruitment and recovery potential of the Mahoning will improve greatly.

Pennsylvania

Wildlands Conservancy led efforts in Pennsylvania with eight dam removals in 2024. They removed six dams from the Archibald Johnston Conservation Area along the Monocacy Creek (all 4 to 8 feet tall). They also worked with the City of Easton and local agencies and partners to remove the City of Easton Lower Dam (aka Recycling Center Dam) (10 feet tall). That project was part of a larger aquatic connectivity effort to remove the first several dams along the Bushkill Creek to restore free flowing conditions to the Delaware River and Atlantic Ocean. They also partnered with PA Game Commission and PA Fish & Boat Commission to restore native brook trout habitat through the removal of a dam along SGL 129 on Dilldown Creek in Tunkhannock Township (Monroe County) (6 feet high).

New Jersey

On the eastern side of the Delaware River Basin, The Nature Conservancy removed two dams. The Paulina Lake Dam (13 feet high) removal was the final step in a four-dam removal watershed-wide restoration. The removal of all four dams on the Paulins Kill River (Columbia Remnant Dam (2018), Columbia Lake Dam (2019), County Line Dam (2021), and Paulina Dam (2024)) reconnected a total of 45 miles of mainstem and tributaries for migratory fish species including American shad, American eel, and sea lamprey. Partners (so important!) on that project included Blairstown Township, New Jersey Department of Environmental Protection, and U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. In addition, the removal of the Cedar Grove Dam (8 feet high) from the Pequest River will amplify the impact that the removal of the three most downstream dams (in progress) will have on restoring aquatic connectivity and improving water quality for the benefit of fish and wildlife in the Delaware River Basin.

Collectively, the Mid-Atlantic dam removal projects from 2024 completed by American Rivers, our partners, and others reconnected more than 470 upstream river miles for the benefit of fish, wildlife, and local communities. A significant amount of time, effort, and resources went into these projects that will have innumerable benefits. This goes to show that the dams do not need to be tall to make major differences for rivers. Each dam removal plays a role.

You play a role too. We need you to reach out to your legislators and tell them that funding for river restoration and clean water are important to you! Tell them that you want our country to invest in healthy rivers for future generations.

What dams should we remove in the Mid-Atlantic in the coming years? Are there opportunities in your neighborhood? If you think there is a willing landowner, let us know about it.

The investment in our nation’s infrastructure in recent years is paying off. In 2024, we finally saw a rebound to pre-pandemic levels of dams removed across the country, with 108 dams demolished. Seeing momentum building once again for reconnecting and restoring rivers brings hope during an otherwise challenging time.

This year we saw excellent work happening across 27 states. More than 2,528 miles of river were reconnected across the country. This is fantastic news for our local communities, who benefit from safer places to recreate without the looming threat of a dam failure.

Those numbers include 400 miles of river reconnected in the biggest collective dam removal project in the country on California’s Klamath River. The Copco 1 Dam, Copco 2 Dam, Iron Gate Dam, and John C. Boyle Dam are no more, thanks to the tireless efforts of tribes and partners on the ground.

California is not the only state with multi-dam removal efforts happening along a particular river. In Pennsylvania, two six-dam removal projects happened in 2024 — this has helped keep Pennsylvania as the leader in dam removal, with 27 dams removed last year! Other states knocking them down in 2024 included Michigan (10 removals), Minnesota (7), and Virginia (7).

Examples include:

- The Forest Preserve District of Kane County, Illinois, removed the first of a series of nine planned dam removals on the Fox River, starting with Carpentersville Dam in 2024.

- The Nature Conservancy in New Jersey removed Paulina Dam on the Paulins Kill River—the final piece of a four-dam removal puzzle to reconnect 45 miles of river for migratory fish, including American shad, American eel, and sea lamprey.

- Wildlands Conservancy continues to bust barriers on Bushkill Creek in Pennsylvania by removing the City of Easton Lower Dam in 2024.

- Green River Lock and Dam No. 5 was removed by The Nature Conservancy in Kentucky, building upon the previous removal of Dam No. 6 in 2017.

- The Warren Water Works Summit Street Dam was removed from Ohio’s Mahoning River as part of a large, regional effort to remove low head dams and restore water quality and habitat.

The list goes on. Focusing on reconnecting rivers through a series of removals maximizes the impact of a single project, providing even greater benefits for community safety and river health.

Here comes the challenge: these projects have major benefits—from fish passage to removing stagnant dead zones to making rivers safer for paddlers and swimmers and more— but they come at a financial cost. Removing 108 dams in 2024 cost tens of millions of dollars. Some dams can be removed for tens of thousands of dollars, but most cost between $250,000 to $500,000. Most individual dam owners cannot shoulder that cost on their own, hey need help from the broader community. In many cases this means removing dams that were built a century or more ago. Three of the dams removed in 2024 were built in the 1700s! These structures were never intended to last forever, but it takes all of us coming together to build a healthier future for our rivers and communities.

We need your help. We need you to reach out to your legislators and tell them that funding for river restoration and clean water are important to you! Tell them that you want our country to invest in healthy rivers for future generations. As we say, Life Depends on Rivers. We need you to lend your voice so that elected officials know that people value healthy rivers. If we do not prioritize removing dams in a controlled way, they will remove themselves and it will not be fun for anyone. If you’re wondering if there are any dams near you, check out the National Aquatic Barrier Inventory and Prioritization Tool. Then take action to support removing dams in your community!

In the meantime, if you want to learn more about some of the great projects completed in 2024, check out our annual summary!

We expect to hear a lot about energy in President Trump’s address to Congress on Tuesday night. One of President Trump’s latest executive orders “Establishing a National Energy Dominance Council,” aims to grow domestic energy production by changing “processes for permitting, production, distribution, regulation and transportation across all forms of American energy.”

The relationship between rivers and energy development may not jump right off the page. Still, fast-tracking energy projects or lifting public safeguards energy projects, like hydropower dams, will have an impact on rivers – our most important source of drinking water.

Therefore, finding a true balance between river protection and energy development will be vital to ensuring success in achieving President Trump’s other stated goal of having the cleanest water in the world.

Water Availability:

The energy sector is a water-hungry industry. Water is utilized in and sustains the economies of communities throughout the country. When rivers and watersheds are protected and managed responsibly and sustainably, everyone benefits, water availability is increased, and demand is better met. Conversely, improper, unrestricted use that doesn’t prioritize water recharge and downstream water availability will raise costs for both consumers and the energy sector. This is especially true in the era of extreme weather and more frequent droughts.

River Temperatures:

Power generation – and many industrial processes, like those used in new AI data centers – require significant water withdrawals for cooling and often source from rivers. When that water is discharged, it is often warmer and can significantly impact plants, animals, and overall river health. Warmer water can impact fish such as trout – a cornerstone of valuable recreation and tourism economies. Increased temperatures also lead to increases in toxic algae outbreaks, which can shut down municipal water supplies and be deadly to wildlife, pets, and livestock. Warmer water also has an impact on water quality, so it drives up the cost of treatment.

Water Quality:

Mining for fossil fuels and combustion processes creates pollution and can cause silt and dust and even heavy metals like mercury, arsenic and lead to leach into our rivers and drinking water sources. Countless communities across the country, and particularly in rural communities, already deal with acid runoff daily from mining done generations ago. Rushed or unbalanced decision-making could extend this polluting legacy that makes America anything but great. Put simply, rivers cannot absorb this pollution and still sustain natural function and be a resource we rely on. Dirty rivers also can’t sustain thriving communities.

Concerningly, the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers has already fast-tracked 600 projects, including pipelines, oil terminals and mining projects, potentially circumventing the Clean Water Act and opening the door to increased pollution.

Cost of living and local economies:

Monthly water bills are already taking a major bite out of Americans’ household budgets. More pollution will make water more difficult and expensive to treat, driving up bills even more.

Pollution will also harm local economies — impacting everything from real estate values to businesses dependent on fishing, hunting, hiking, boating, and tourism. The outdoor recreation economy generates $887 billion in consumer spending, 7.6 million jobs, and it generates $59.2 billion in state and local tax revenue. Many communities depend on recreation to support their prosperity, and a dirty river is not a place people want to visit.

American Rivers’ Take:

Ultimately, this is about the people of our country. Health and safety are important to us all. American Rivers Action Fund has done polling that shows Americans care deeply about their rivers and access to clean water. In fact, clean water polls much higher than voter concern about energy.

As the Trump administration establishes and implements its energy goals over the next four years, our nation can learn from the mistakes of the past. We must leverage new and emerging technologies that allow energy development in safer ways and clean and healthy rivers to coexist, and we must stay true to common sense regulatory safeguards.

Common sense starts with maintaining an appropriate permitting regime to protect water resources from industrial development that threatens clean water – especially in areas prone to extreme weather. The Clean Water Act and its associated permits, particularly through the Army Corps of Engineers, are designed to enable the growth of industrial development and the energy industry while protecting our nation’s clean water resources from pollution. If anything, public safeguards should be strengthened and considerate of models that consider extreme weather events.

Continued public investments and federal workforce staffing in technology are necessary to ensure we have the cleanest water in the world while expanding the energy sector. Technologies that reduce water needs, ensure warmer or dirty water is not discharged or otherwise injected, and reduce pollution that exacerbates atmospheric changes are important to keeping rivers healthy.

Expanding other public safeguards to mirror “kindergarten rules” would create common sense most can agree with when it comes to energy and water. Rules, like “clean up your own mess,” would go a long way towards ending legacy pollution and ensuring no community with precious natural resources is forgotten because of extraction or power generation. Communities should not be left with permanent toxic waste sites in their backyards and legal safeguards should be put in place so that those who make money off these industries must be good neighbors to those most impacted.

Rivers and clean water are one of our most important resources as a country – especially freshwater. Taking care of it as we work towards other goals, like greater energy development, will be important to protect it.

When it comes to protecting clean water in the United States, it truly takes a village. Of course, the EPA and other agencies focused on water and infrastructure play a large role, but believe it or not, so does the Department of Justice. For over 100 years—through Republican and Democratic presidencies—the Department of Justice has enforced the nation’s civil and criminal environmental laws, including the Clean Air and Clean Water Acts. In order for these Acts to have meaning, they must be enforced. These enforcement efforts have resulted in significant public health benefits to the American people through the reduction of pollution and the protection of important natural resources.

Unfortunately, the Trump administration recently began shutting down two key sections—the Law and Policy section and the Office of Environmental Justice—within the Environment and Natural Resources Division (ENRD) of the Justice Department. Both sections play important roles enforcing environmental laws and ensuring public health and limiting exposure to pollution.

The administration also began reassigning key additional attorneys. The attorneys leading ENRD, the Appellate Section, the Environmental Crimes Section, the Environmental Enforcement Section, and the Natural Resources Section were all reassigned to positions focused on immigration—specifically “sanctuary cities.” It also suspended a 75-year-old Honors Program for entry level attorneys. This program has been a constant through many administrations—hiring some of the best attorneys out of law school to staff the division.

Understaffed, it will be difficult if not impossible for the Department of Justice to keep up enforcement and to keep our communities safe and healthy.

One example of the critical role these two offices play can be seen in a recent case in North Carolina. Over a four year period, an employee at American Distillation Inc., a chemical processing company near Wilmington, was illegally dumping over 50,000 gallons of chemical pollutants directly into the Cape Fear River. This was just upriver of the popular Carolina Beach State Park. They were doing this to cut corners but were exposing local communities in the area to toxic chemicals. The Justice Department’s ENRD successfully targeted the source of pollution and took the lawbreakers to court. They obtained a guilty verdict and efforts to remedy the damage have begun.

Additionally, while the pollution was impacting the Cape Fear River through Wilmington, NC and affecting its beaches, it was also being dumped near the small town of Navassa, NC, adjacent to Wilmington, where over 60% of the community is Black and where many people actively fish and boat on the river. It is part of the Department of Justice’s job to protect communities like Navassa, which suffer from pollution exposure at a much higher rate than white communities.

Another example, Avin International and Kriti Ruby Special Maritime Enterprises two Greek shipping companies that were falsifying records to conceal their dumping of oily bilge water into American Harbors in Jacksonville, FL and Newark, NJ. The Department of Justice took them to court, secured guilty pleas, and they are now paying multi-million dollar fines.

The point is, some bad actors pollute to save money and cut corners, trying to avoid complying with laws meant to protect our health and well-being. Their actions directly impact communities, and put the burden on others to clean-up.

We can’t risk letting polluters off the hook. These offices play a critical role in protecting the health and safety of our rivers and clean water. Shutting these offices down, moving out experienced attorneys, and freezing the hiring of new ones, will only further endanger our communities.