Let Milwaukee Rise

Can one of the country’s most segregated cities come together around water?

Part of our ethos is building a multiracial, multicultural environmental movement on behalf of the water. And we’re looking to do that regionally. We’re looking to do that within our own organization and within our city

Brenda Coley, co-executive director, Milwaukee Water Commons

Brenda Coley and Kirsten Shead are on the same wavelength. Equally outspoken and mutually admiring, they regularly finish each other’s sentences. In fact, I’m not sure that I’ve ever talked with two colleagues who are so totally in-sync. And nowhere is this mind-meld more needed than in Milwaukee — one of the country’s most deeply segregated cities.

Together, Brenda and Kirsten co-lead Milwaukee Water Commons, an organization seeking to repair Milwaukee residents’ relationship with water. But perhaps more importantly, they are turning the status quo on its head and driving a city-wide conversation about what environmental conservation should look like, who should have a voice, and how decisions should be made.

Kirsten: “I think part of what makes our co-executive model unique, besides just really liking each other and working well together, is that it is collaborative at its core. It’s not you take this and I’ll take that…”

Brenda: “…or I’m in charge of this. You’re in charge of that…”

Kirsten: “…We really feel like part of what we’re doing is modeling, in a hyper-segregated city, Black and white leadership. We’re modeling what women-centric leadership looks like. And many of our programs have co-leaders. So that idea of collaboration is everywhere — that any one person or any one culture is not going to be able to solve these problems…”

Brenda: “…that if we’re going to really steward this resource for generations to come, we must build something together. That’s what’s going to be sustainable.”

See what I mean?

Water is literally everywhere you look in Milwaukee — Lake Michigan rests to the east, and the Milwaukee, Menominee, and Kinnickinnic rivers run right down the center. Yet Black Milwaukeeans have historically not been able to enjoy the benefits of these natural treasures due to policies and practices that create and maintain racial inequities.

Redlining — the racist practice of denying People of Color equal lending and housing opportunities — is to blame. Because Black families were intentionally prevented from buying high-quality houses in desirable neighborhoods, families were less able to pass down wealth through the generations. Pile on an influx of Black migrants in the 1960s and the fact that Black voices have been systemically sidelined from power and you are left with a chasm between Black neighborhoods and white neighborhoods that persists to this day. Black neighborhoods like those on the city’s north side are poorer, have fewer parks, and less access to nature. White neighborhoods are wealthier and closer to the lake.

Let's Stay In Touch!

We’re hard at work for rivers and clean water. Sign up to get the most important news affecting your water and rivers delivered right to your inbox.

This disenfranchisement carries a dangerous legacy: Around the country aging cities like Milwaukee are facing an infrastructure crisis. The American Society of Civil Engineers gave water infrastructure in the United States a C- grade. Communities of Color are ground zero due to a woeful lack of investment. That is doubly true in Milwaukee, which also faces an unseen emergency: lead piping. More than 40 percent of households in the city — over 66,000 homes — have lead water pipes. Lead poisoning causes kidney and brain damage and harms children’s nervous systems. More than 70,000 laterals in Milwaukee need to be replaced, and the vast majority of those are in Black and brown neighborhoods. “They are bringing the risk of tainted lead into people’s homes,” Brenda says.

The city has been slowly replacing its lead lateral lines, but on the current trajectory, a child born today could be 70 years old before their home’s line is updated. Thankfully, Wisconsin received $79 million through the bipartisan infrastructure bill, and a large portion of that money will go toward helping Milwaukee replace lead pipes. But the investment is just a start. In 2021, the city estimated that replacing every Milwaukee lead lateral would cost about $800 million.

Milwaukee Water Commons is working with state and local governmental agencies, and institutions to build urgency around the problem. The organization is also helping local people understand the dangers of lead in water and giving them the tools to advocate for change.

Kirsten warns against box checking, though: “We have to engage communities earlier and in a more authentic way, so that we don’t go all the way down the path of a solution that’s disconnected from the lived experience.”

Innovation at the grassroots

Honoring and centering lived experience is a key tenet of the cultural shift Milwaukee Water Commons is trying to spur. The bottom line is this: To create positive, lasting change, the people who live near, rely on, and are impacted by the health of their water must have a firm role in crafting the solutions. Historically, though, government and the environmental community haven’t made space for local people — particularly People of Color — in decision-making process.

Brenda: “[Government and] big greens know that the problem is happening — they know there’s lead in the water. But they don’t know how the problem really sits on people. Engaging the community is not just the right thing to do, it’s the necessary thing to do because really that’s where the innovation is. If we want to find out how to solve our issues and our problems, we need to be talking with people.”

Kirsten: “We need to be asking, ‘What is the lived experience of people navigating basement flooding in Milwaukee? We need to hear that at the beginning and have a community-informed vision that is much more grounded in people’s experience.”

The same people who are most impacted need access to power and to spaces where their voices can be heard. Brenda is careful to point out, though, that the process is more involved than just gathering people in a room. “We can’t just convene a meeting about something super wonky and say to community members, ‘What do you think?’ They won’t be able to respond. To me, we’re talking about informed decision-making. We’re getting paid to do this work, but we need to check in with the community and find out if this is the right way to go. Sometimes that means we need to lay out the issue and giving them the information so they can make the decision.”

So, what does community engagement look like in practice?

A safer lake for Milwaukeeans

During the pandemic, when everyone just needed a break — to get into fresh air — Milwaukeeans flocked to Lake Michigan to lounge on its sandy beaches and wade in its chilly waters. There were no lifeguards. But the lake looked smooth. It looked like fun. Black residents who had long been disconnected or made to feel unwelcome at the lakefront had never been given information about how to enjoy their lake — and its currents — safely. And the results were disastrous. Four Black men died in separate drowning incidents. Most were trying to save children.

Nationally, Black people are far more likely to drown than white people. The fact that Milwaukee’s Black community lacks access to safe recreation on Lake Michigan doesn’t help.

“I mean, Milwaukee is a city on the water,” Kirsten says. “But you can live less than a mile from Lake Michigan and have never seen it. And if you do get there, if you’re hyper policed or you’ve never experienced swimming, you’re more likely to experience a drowning.”

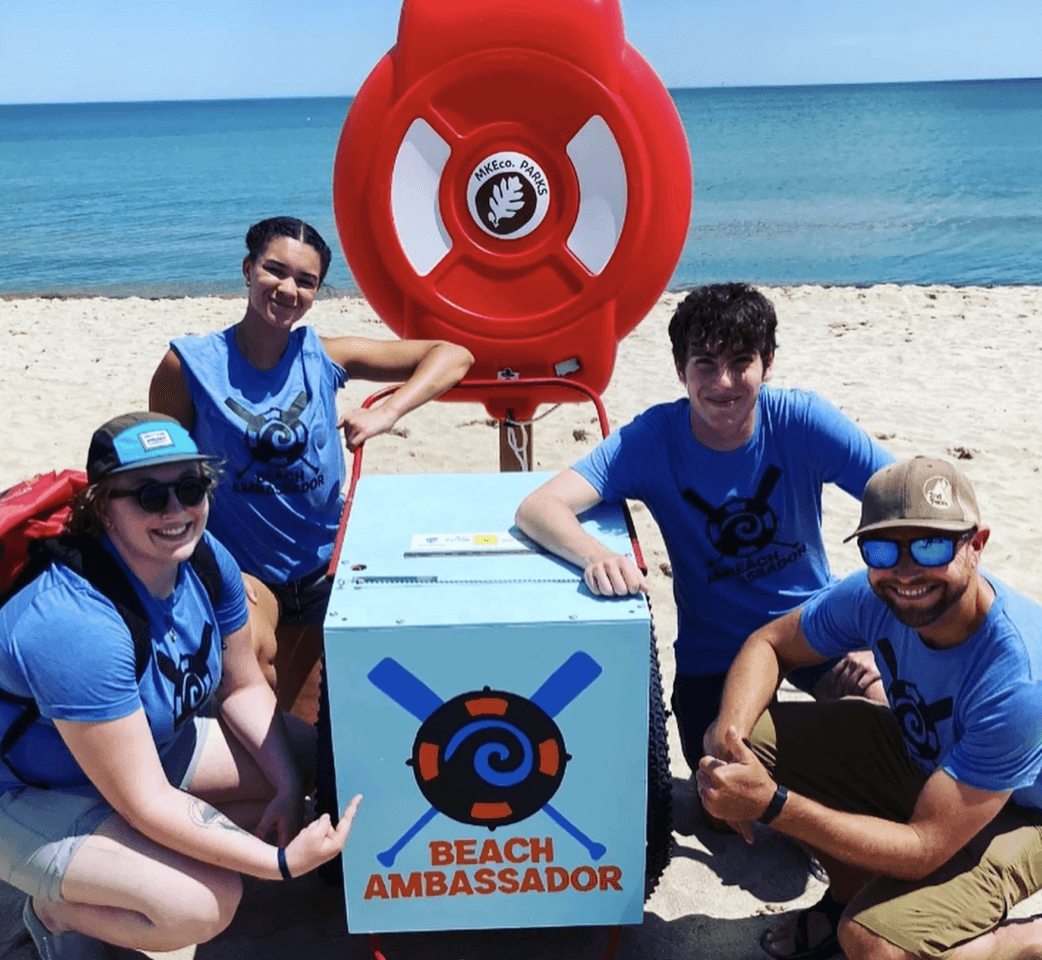

Milwaukee Water Commons recognized the problem and swung into action, forming a “beach-ambassador” program in which young People of Color interact with folks on the beach, educating them about rip tides, currents, and where it’s safe to swim and where it’s not.

“The question was,” Kirsten says, “can we get this knowledge into community hands so that people can make informed decisions? It’s not our job to keep people in or out of the water, but if we give them the information, they can make a more informed decision and can be safer.”

Not only has the program increased awareness about water safety, but also community members are leading the charge on a solution that has legs. Meanwhile, the municipal government is still deciding what to do.

“We’re changing culture around water,” Brenda says, “making sure that people understand that we all belong here. So, we shouldn’t get funny looks when we’re down at the lake. This is all our water.”

Inspiring urban water leaders

Perhaps one of Milwaukee Water Commons’ most successful programs melds education, community engagement, recreation, and celebration. During its summer Water School, the organization hosts teams of adults from other nonprofits, churches, and community-based organizations. One day every month, the teams gather in a different part of their watershed to kayak, swim, fish, and learn about water-related issues. What is their water footprint? How do watersheds work? What are the issues affecting in Milwaukee? How are decisions made around them?

“We’re working with people who don’t normally have these experiences — and connecting folks with the beauty of the river,” Brenda says. “We bring in native folks and Latino folks and Black folks into spaces that are traditionally very white. At first, it’s a little awkward for them, but after a minute or so, everyone’s transformed and happy.”

The program includes a leadership development component that has birthed some of the cities strongest water leaders. Local people who have participated in the program now sit on community advisory committees. They have testified at state discussions around drinking-water access. And many have infused water into work they were already leading.

It’s a model for how to spread information, empower local advocacy, and shift the culture of water and rivers. The community is taking notice, says Kirsten: “Our rivers are really being celebrated more and more in Milwaukee. And more people are making the connection that these spaces are our spaces.”

Solidarity is the future

Enormously effective local organizations, like Milwaukee Water Commons, are working in communities around the country. They are protecting rivers, making rural and urban waterways healthier, connecting more people to nature, and advocating for equity in how decisions are made around water and our environment.

National groups like American Rivers can play an important role in supporting and advancing their work. We can be strong allies for local groups — particularly those led by People of Color — by addressing power inequities sharing access to decision-making spaces. We can make introductions to people and foundations who can fund their work, and we can pull community-based organizations into discussions they might not otherwise be in. It’s a symbiotic relationship. Because relationships with community-led organizations are absolutely essential for national environmental nonprofits to advance programs on the ground — and to achieve meaningful national policy wins. Local groups act as a bridge to communities, helping build trust and inform the conservation work and priorities of groups like American Rivers.

“If I look at what American Rivers has done for Milwaukee Water Commons, in many ways, they put us on the national scene by introducing us to funders,” Kirsten says. “And then, of course our work spoke for itself. American Rivers recognized the quality and the scope of the work that we do, being ahead of the water sector in many ways around equity, justice, and environmental justice, and really playing a role to transform the movement as we transform our own organization.”

Looking ahead

Nearly everyone in our country lives within a mile of a river but few know what that river provides. Much of our drinking water comes directly from rivers, and clean water is essential to our health. Natural river habitats support thousands of plant and animal species. Our crops and cities alike depend on abundant river water for growth. For many of us, rivers offer recreation and a way to connect to nature. For others of us, our rivers have been sources of pain, sickness, and struggle — or we didn’t even know they were there.

American Rivers believes healthy rivers are for everyone, not just a privileged few. We will not achieve our mission until we dismantle policies that allow damaged, polluted rivers to flow through Communities of Color, while more affluent — often white — communities enjoy cleaner, healthier rivers.

The way forward must be rooted in collaboration. It must include greater partnerships between organizations like American Rivers and Milwaukee Water Commons and deeper engagement with communities that deal with river and water issues every day. Together with advocates like Brenda and Kirsten, we can champion a movement to improve the health of communities and their water. Because at the end of the day, that is our best hope to equitably provide the benefits of healthy rivers and clean water to everyone.

Learn more about Milwaukee Water Commons’ work at www.MilwaukeeWaterCommons.org.