Merrimack River

A hard working river making a comeback

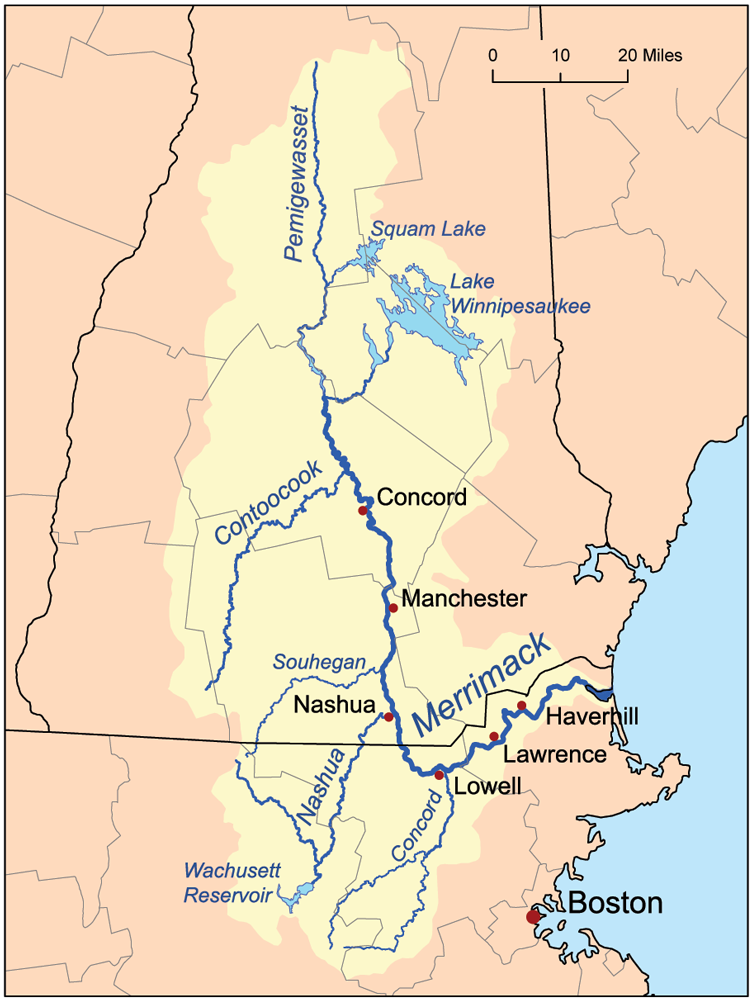

The power of a river has attracted humans for thousands of years, where successive waves of technology has allowed human communities to thrive and flourish. The Pawtucket Falls are a dramatic 32-foot-high set of falls located in Lowell, Massachusetts upstream from Newburyport, Massachusetts where the river drains into the Gulf of Maine. For thousands of years the indigenous Penacook, Agawam, Naumkeag, Nashua, Souhegan and the other tribal nation members of the Pennacook Confederacy developed technology of weirs, nets, and other structures to harvest the abundant migratory fish at the falls and throughout the over 5,000 square mile watershed as habitat.

European explorers made contact in the 16th century here and later colonists adopted what they heard as the name of the river as the Merrimack, which in Algonquin translates to a “place of strong current.” The watershed’s mainstem and tributaries include numerous falls arising from the 117-mile descent from the source in the high mountain elevations in central New Hampshire. The power of those many falls are central to the story of the Merrimack.

By the early 18th century European colonists began introducing their technology of canals, dams, and water powered mills. This well-trod history of settlement and industrialization throughout the 18th, 19th and 20th centuries created wealth and technological innovations as well as pollution, and dramatic declines in the migratory fish that had sustained humans for tens of thousands of years. The industrialization of the Merrimack was built on centuries of impacts to the indigenous nations including epidemics, forced displacement, and warfare.

Since the passage of the federal Clean Water Act in 1972 the health of the Merrimack River has improved dramatically. While New England states were early actors in establishing state water quality standards and permits in the 1940s through the creation of the New England Interstate Water Polllution Control Commission, it wasn’t until the 1972 amendments to the Federal Water Pollution Control Act were enacted that significant progress on restoration began.

Today the cities and towns in the watershed operate under federal and state permits and have required plans to meet federal requirements to dramatically reduce combined sewer overflows and stormwater pollution. Environmental advocates in the watershed deserve great credit for ensuring these changes were made, including the Nashua River Watershed Association. The NRWA began work in the early 1960s as an informal group of citizens and its brand of creative advocacy and the tireless work of Marion Stoddard and others helped to launch river advocacy organizations around the country.

The legacy of dams on the river presents significant challenges to the restoration of migratory fish species. There are likely over a thousand non-functional dams throughout the watershed as well as six mainstem and dozens of tributaries with hydroelectric dams. Many of these smaller hydroelectric dams are in disrepair and generate only small amounts of electricity. All these dams present challenges to restoring the health of the river and its tributaries.

What’s the plan?

Federal, state, local and regional governments have developed plans to guide the river’s restoration. Among the ones that American Rivers relies upon is the Merrimack River Watershed Comprehensive Plan for Diadromous Fishes. This plan is a product of a collaboration of state and federal agencies working together for decades to set restoration goals, evaluate progress, and make management decisions in coordination with the public.

This plan and others guide the work of American Rivers and local partners in identifying projects that have the highest impact for migratory fish and our communities.

What’s new?

American Rivers is partnering with the Towns of Milford and Jaffrey, NH and the Souhegan River Local River Advisory Committee and the Souhegan Watershed Association to advance the removal of dams on two tributaries of the Merrimack River.

Partners working in the watershed

Nashua River Watershed Association – The Work of 1000 documentary

Merrimack River Watershed Council

OARS 3 Rivers

Souhegan River Local Advisory Committee

Souhegan Watershed Association

Upper Merrimack River Watershed Association

Upper Merrimack River Local Advisory Committee

Lower Merrimack River Local Advisory Committee

Contoocook River Local Advisory Committee

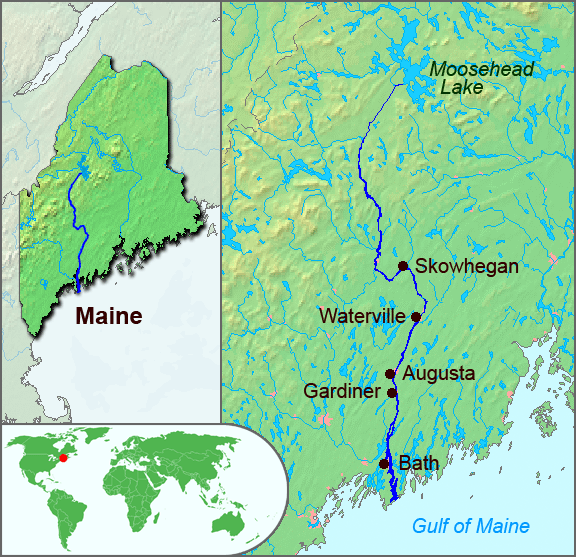

Kennebec River

The Kennebec is one of Maine’s major river systems that reaches from the Gulf of Maine high into the central heart of the state where Moosehead Lake feeds its headwaters. Its almost 6,000 square miles of watershed have sustained human communities for thousands of years. Like many other large coastal watersheds, the Kennebec River watershed supports habitats for all migratory fish species as well as a diversity of resident cold-water fish species. The natural topography and dams have created an important white-water economy on the upper reaches.

The watershed has been home to the Algonquin nations for millennia and early European settlers established forts and trading posts on the coast and near the fall-line in Augusta in the early 17th century.

Did You Know?

The last log drive on the Kennebec River was in 1977, decades after the practice has stopped on the other New England Rivers.

Merrymeeting Bay is the mouth of both the Kennebec and Androscoggin Rivers, which come together along with 4 other rivers to create the 17-mile long riverine estuary that drains to the Atlantic Ocean. The Bay is sustained by over 20,000 square miles of the state’s watersheds.

What State Does the Kennebec River Run Through?

Maine

Three Centuries of Damming the Kennebec River

Since European settlement, the Kennebec and many of its tributaries have been heavily dammed and modified to support mills, the timber industry, and industrial development including pulp and paper manufacturing. The upper reaches of the river support 9 hydropower stations, including Harris Station, the state’s largest hydropower generator. These dams and the many other small ones throughout the watershed served to support the economy of Maine for generations but also completely blocked off hundreds of miles of habitat for migratory fish, including some of the best habitat for the endangered Atlantic salmon on the Sandy River tributary.

That history began to change on July 1, 1999. It was a bright sunny day as the excavator slowly inched forward from the right bank of the river on the earthern berm built on top of the Edwards Dam. Hundreds of people watched the slow advance from both sides of the river, waiting for the signal. Given the green light the excavator operator deftly reached out and breached the timber crib structure that had blocked the river for over 160 years.

As the river poured through the initial breach the crowd cheered and in a bit of serendipity a number of short nose sturgeon leapt from the river as the flow dramatically increased. Cheers and leaps for the opening of the first dam on the river!

While a dam removal today may seem ordinary, in 1999 the demolition of Edwards Dam was a remarkable transition in how the federal government understood the balance between hydropower and free-flowing rivers. This removal was the first time that the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission authorized the removal of an active hydropower facility. Edwards Dam was a very small hydropower project that entirely blocked the Kennebec River, home to migratory fish including the endangered short-nose sturgeon and then recently listed Atlantic salmon.

Since 1999 many more dams have been removed throughout the watershed which has supported dramatic improvements in returns of migratory fish particularly in the Sebasticook River tributary. There is, however, much more work to be done as we seek to set a better balance between the dramatic ecological potential of this river and the energy and water needs of people and industry.

The removal of the Edwards Dam initiated an agreement for how upstream dams would be required to install or improve fish passage as migratory fish returns increased. This agreement signed by the dam owners and the coalition of environmental organizations – including American Rivers – set triggers for the dam owners to make improvements over time.

This agreement has proved challenging to all sides and has brought the many parties – owners, state and federal agencies, conservation organizations, and the public – to an essential standstill while federal licensing proceeds. Between 2021 and 2024 there has been on-going analysis, debate, and commentary on whether removal of four dams that are rated for a total of 45MW (a very small percentage of the state’s energy needs) just upstream of the former Edwards Dam site is a better solution than installing and operating new and modified up and downstream passage for all migratory species.

Whatever the results of this debate it will again set the Kennebec River as an example of how we think and act on behalf of rivers and the many communities – human and otherwise – that they support.

What’s new?

In the summer of 2024, the long-running conversation about how to balance uses on the Kennebec reached another milestone with a series of public hearings held by the National Marine Fisheries Service. These hearings were to receive comment on the Service’s proposed environmental impact statement that outlined plans for improvements in fish passage at four hydropower dams upstream from the former Edwards Dam site. American Rivers weighed in with the overwhelming majority of comments opposing installation of fish passage and recommending removal.

Partners Working in the Watershed

Maine Rivers

Atlantic Salmon Federation

The Nature Conservancy in Maine

Natural Resources Council of Maine

Conservation Law Foundation

Huron River

A candidate for improved protection status

The Huron River emerges in southeastern Michigan in Springfield Township near Big Lake, flowing roughly 125 miles through a variety of landscapes. From densely wooded banks to current and former mill sites and mill dam impoundments; through scenic villages such as Milford, and larger cities like Dexter, Ann Arbor, and Ypsilanti; and finally opening up through rolling farmland before it empties into Lake Erie. Two million people live within roughly ten miles of the river, but when you are on the river you wouldn’t hardly believe it.

The river is known for its fishing, recreation, and Native American village sites. It provides for a wide range of quality gamefish species such as smallmouth and largemouth bass, trout, and steelhead. The Huron River Water Trail, a part of the National Water Trails System, provides an exceptional 104-mile long water-based recreational opportunity for paddling, fishing, and hiking through a significant number of public access sites.

Building on the success of the Water Trail, many of the communities along the river have committed themselves to improving their relationships to the river. These communities are engaged in conservation and access projects that are helping to improve the health of the river and ensuring residents nearby have access to it, regardless of their socio-economic status. With a long history of projects, the Lower Huron River Watershed Council, which represents many of the communities along the lower part of the river, has been championing restoration efforts, including assessing and/or pursuing removal of outdated dams, such as the Flat Rock and Peninsular Park dams.

The Huron is currently designated as the only Country-Scenic Michigan Natural River, a state river protection program administered by the Michigan Department of Natural Resources. We believe that the Huron could benefit greatly from a national “Partnership” Wild and Scenic River designation based on our analysis and discussions with local community members.

Partnership Wild and Scenic Rivers are a unique category of designated rivers managed through long-term partnerships between the National Park Service and local, regional, and state stakeholders. This locally driven, collaborative planning and management approach to river conservation is an effective model anchored by annual federal funding put into the hands of local community members. Partnership Wild and Scenic Rivers program has a 20+ year track record of successful partnerships, with 18 designated rivers in 8 states covering more than 700 river miles. (Source NPS.)

American Rivers is excited to work with our local partners in Michigan to explore studying the Huron River for Partnership River status. This status would help support the many successful programs on the Huron River. We are especially grateful for the support of Michigan’s representatives in the U.S. Congress, including U.S. Senator Peters and U.S. Representative Dingell who have been river champions and who’s staff have expressed support for the Partnership Program and are interested in exploring opportunities to assess the Huron River.

Deep River

A rocky rural beauty with a milltown history

The Deep River, translated from the native people’s name “sapponah,” refers to the steepness of the banks and not the depth of the water. The watershed is characterized by rocky shoals, riffles and outcrops of bedrock and flows within the Carolina Slate Belt. Huge natural rock formations can be seen poking up from the riverbeds at different points along the river creating scenic natural falls.

The River has seen its share of inhabitants over the years. The history of this region is complex. Several eastern Siouan tribes, including the Eno, Occaneechi, Shakori, Sissipahaw and Sara had established communities in the watershed prior to European colonization. Artifacts, and the presence of fish weirs, or structures in the river thought to direct fish to be caught, indicate the presence of the Siouan tribes and their connection with the Deep River. Early European settlers colonized the area in the mid-1700s and used the land for agriculture, logging and mining. Native American presence had a marked decline during this time period and much of their history was lost.

The Deep was historically a ‘working river’ and is dotted throughout the watershed with former mill dams. The mills that were powered by these dams helped to form communities along the river and drive the economy and culture of the region. The manufacturing backbone of the region is still present and active but no longer depends on the dams. Many mill dams have since been altered from their original use to serve as hydroelectric power.

Today, this largely rural part of North Carolina is developing rapidly, and there is a renewed focus on the Deep River and its watershed as an asset for people and nature.

Did you know?

The Deep River was named for its steep banks in many places, and not for the depth of the river.

What states does the river cross?

North Carolina

What’s new?

American Rivers is working on a transformational project on the Deep River, along with partners across the watershed, to reconnect nearly 100 miles of the main channel of the river. The project started in 2023 and we expect it to be completed by 2030.

ABOUT THE RIVER

The Deep River winds through steep banks within a largely rural portion of North Carolina. Stretching 125 miles, the Deep River begins just north of High Point, NC, and flows south and east until it connects to the Haw River where it forms the Cape Fear River. The river is a critical thread connecting the communities within it and providing clean water supplies. It is unique and prized for the natural beauty it supports and by outdoor enthusiasts for paddling and fishing.

Climate change impacts, water pollution and aging dams are limiting the river’s ability to deliver clean water and support resilient natural populations. Investments made into reconnecting the river and prioritizing its health has the potential to not only protect and heal the Deep River but ensure this resource remains an asset to the communities in the watershed into the future.

The river and its tributaries provide drinking water to approximately a quarter of a million people. Near its head waters is the large Randleman Reservoir that was the last major reservoir built in North Carolina for drinking water. It was completed in 2004 and serves the population of the Triad. There are dozens of additional smaller reservoirs throughout the watershed that provide water supply to communities like Randelman and Franklinville and businesses that still dot the banks of the river. The agricultural production in the watershed counts on reliable flows in the river for irrigation and drinking water for livestock.

The Deep River is a quiet ecological jewel in North Carolina with a diversity of interconnected species that call it home, including rare and endangered freshwater mussels that pump millions of gallons of clean water into the river, endangered fish species that only call the Deep River home and river otters that can be found playing in the shallows and along the muddy banks.

In the Deep River, and in rivers everywhere, aquatic species are interconnected. They all work together in a complex ecosystem that affects us all. For example, freshwater mussels rely on fish to complete their life cycle and mussels are crucial as they filter the water returning clean water to the river. Many freshwater mussels rely on free-flowing water and gravel and pebbles on the riverbed to survive and reproduce. The state-endangered Brook Floater, the federally threatened Atlantic Pigtoe, Savannah lilliput and Yellow Lampmussel, and the state-threatened Triangle Floater and Creeper are all freshwater mussels that live and depend on a healthy Deep River. The federally endangered Cape Fear shiner is a fish found nowhere else on earth. It relies on clean, shallow river beds composed of gravel and cobble to be able to survive and thrive. The Deep River is also historic habitat for numerous migratory fish species like American shad, River Herring, Striped Bass, Atlantic Sturgeon and American eels – all of which are blocked from reaching the habitat in the Deep River due to downstream dams.

Recreational paddling and fishing are popular on the Deep River. There are many parks lining the river and several kayak routes that wind through undeveloped landscapes where paddlers are likely to spot blue herons and basking turtles. Anglers fish along the riverbanks or in small boats. The Deep River State Trail, which was designated in 2007, is currently under development in the upper portion of the river. The vision for the trail, when completed, is to connect the communities of the Deep River by providing paddling and hiking opportunities through a combined blueway paddle trail and a greenway along the entire length of the river.

THREATS

Along the entire Cape Fear River system, there are an estimated 1,100 barriers including locks and low-head dams. The Deep River is home to several of them, including High Falls dam, which has blocked free-flowing water for more than a century. Many of the dams existing in the Deep River no longer serve a purpose. In fact, it is estimated that 85% of dams in the U.S. are unnecessary, harmful or even dangerous. Low-head dams have been associated with hundreds of drownings as the result of the dangerous hydrologics that form at the bottom of a dam.

Dams built throughout the late 18th and 19th centuries served as grist-mill and sawmills, or were part of a lock and dam systems to transport materials. In the early and mid-20th century, eight low-head dams within the Deep River watershed were repurposed to provide some remaining value by generating hydropower. In 2018, Hurricane Florence flooded many of the dams along this river system, several of which have considerable damage and active leaks. Many no longer produce power and require costly maintenance. Aging dams have the potential for failure and are liabilities for the dam owner and for the downstream community.

The Deep River is also challenged with water quality issues and contamination. This watershed is in a rural part of the state, but it is urbanizing due to exurban sprawl driven by development along the I-85 corridor in the Triad region and the U.S. 64 corridor west of the Triangle. Increased development in the region is creating stress on the Deep River system. Pollutants like excess sediment, phosphorus and nitrogen flow into the river because of failing water infrastructure like outdated wastewater treatment plants and stormwater run-off from agricultural lands and development. People and nature are impacted by the water quality in the streams and rivers of the Deep River watershed.

Climate change exacerbates many of the threats already present in the watershed. As storms become more frequent and more severe, the dams along the Deep River become increasingly susceptible to damage.

BENEFITS OF DAM REMOVAL IN THE DEEP RIVER

The implementation of a watershed-scale restoration project in the Deep River has the opportunity to reconnect fragmented habitats, restore natural water flow and meet environmental challenges. Removal of the dams on the main stem of the Deep River could bring a return of many of the migratory species once known to inhabit the river. Looking towards a sustainable future for the Deep River watershed means putting in place a myriad of protection and conservation measures that would allow for resilience and adaptation.

American Rivers is working on a transformational project on the Deep River, along with partners across the watershed, to reconnect nearly 100 miles of the main channel of the river. The project started in 2023 and we expect it to be completed by 2030.

Natural flowing river systems transport sediment downstream, allowing for floodplain connection and exchange of nutrients. Removing dams allows the sediment collected behind them to be dispersed, and for a natural wetland riparian buffer to be restored as native plants will grow once again in the formerly impounded areas.

Healthy riparian buffers are incredibly important to water health as they filter pollutants, provide habitat, help absorb flood waters, and shade the rivers. Additionally, native plants and trees remove carbon from the atmosphere. The more native plants and green space in a river system, the more resilient a river will be to withstand climate events.

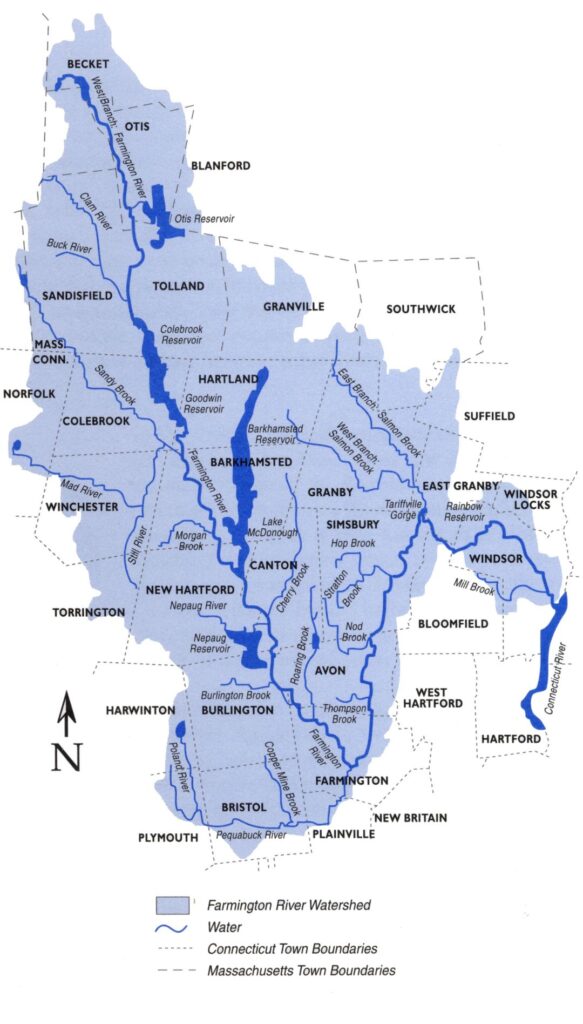

Farmington River

Sustaining Life for Millions

The Farmington River watershed covers over 600 square miles in Massachusetts and Connecticut. It holds two national Partnership Wild & Scenic River designations and is a major tributary to the Connecticut River. The watershed has been utilized and stewarded by Indigenous people for more than 12,000 years, and in the 1600s, Algonkian speaking groups such as the Tunxis and Mahican Tribes called this area home. Due to colonization and displacement, there are currently no federally recognized Tribal lands along the river, but descendants of these groups still live throughout Connecticut and surrounding areas.

The Farmington and its tributaries support cold-water resident fish species and habitat for various important migratory fish species. Anglers from around the northeast know the Farmington for its well-managed sport fishery that is sustained by the state’s hatcheries and aquatic habitat restoration and protection programs.

The river also supports a thriving paddling and tubing experience through the middle stretches of the watershed with challenging whitewater through the Satan’s Kingdom gorge.

Over the last decade significant progress has been made removing dams throughout the mainstem and tributaries which has opened up dozens of miles of habitat. Dam removals continue, including the pending removal in 2025 of the hazardous, low-head Lower Collinsville dam. One small former hydropower dam was retrofitted with state-of-the-art generation equipment as well as safe, timely, and effective up and downstream fish passage. The downstream eel passage facility at this project is unique among projects located in the United States.

Did you know?

The Farmington River is one of the largest tributary watersheds to the 410-mile long Connecticut River.

What states does the river cross?

Massachusetts and Connecticut

What’s new?

The Farmington River is listed as one of the 10 Most Endangered Rivers of 2024 due to the problems caused by the small and poorly maintained Rainbow Dam that violates environmental laws. Rainbow Dam is a hydropower facility owned by Stanley Black & Decker.

For rivers in the northeast the Farmington is unusually regulated and managed due to the presence of several drinking water reservoirs built throughout the 20th century to supply drinking water to the Hartford region. These impoundments and diversions are governed by a variety of contracts and management agreements that direct water to downstream users for recreation, fisheries management, and hydropower generation. Today over 400,000 people in an eight-town region around Hartford, the state capital, use water from the upper Farmington River reservoirs.

The spectacular resources of the Farmington River and its watershed have earned it national distinction including through two federal Wild & Scenic designations. In 1994 15 miles of the upper river were granted one of the early partnership designations, which created a collaborative working relationship between the National Park Service, local communities, businesses and conservation organizations. This first designation was followed by a second listing of 62 miles of the lower river and the Salmon Brook tributary in 2019. These designations and existing management agreements have created a strong network of collaboration among state and federal agencies, municipalities, conservation and angling groups, businesses, and the regional water utility.

In 2023 a historic deal was reached that provided for permanent protection of the thousands of acres surrounding a now unused water supply reservoir. The protection of the lands surrounding the Colebrook Lake reservoir is a significant achievement realized through thoughtful actions of the state, conservation organizations, and the regional water utility.

The Future

A vision of the future is often defined by an appreciation of the past. In the past the Farmington was a river that supported hundreds of thousands of migratory fish including salmon, shad, river herring, eels, and lamprey.

A future that brings those fish back is threatened by the first dam in the watershed.

Eight miles upstream from where the Farmington River joins the Connecticut River is the Rainbow Dam, owned by the FRPC. This small hydropower dam has been in operation since the early 20th century, but due to a quirk of law, it has no federal oversight. Federal regulation of hydropower dams requires that a river be deemed “navigable,” and over fifty years ago the Farmington–despite its significant flows and many boaters consistently using the river–was ruled “non-navigable” by the federal government.

The resulting lack of federal oversight and limited state jurisdiction has allowed this small and poorly maintained hydropower project, whose inadequate and outdated fishway often led to fish mortality before it was shut down in 2023, to effectively render more than 95% of the watershed’s habitat inaccessible to river herring, shad, eel, and sea lamprey. The dam is also responsible for creating river conditions in the upstream reservoir that have repeatedly caused toxic algae blooms that can be a health hazard to people, and can be lethal to pets and wildlife. These blooms have forced the state to seasonally close a public boat ramp and a summer camp located on the river to prohibit swimming and boating during periods of the summer. The FRPC’s operation of the dam releases large pulses of water at unpredictable times, harming aquatic life. The state has said these flows harm the river, and the section below the dam is listed as impaired for aquatic life due to flow. Because of its current operation and failure to safely pass migratory fish, the Rainbow Dam causes the Farmington River to be in violation of the federal Clean Water Act and state laws.

Partners working in the watershed

The Farmington River Watershed Association has been working to protect and restore the watershed since 1954.

The Lower Farmington River Wild & Scenic Committee is the partnership working in the nine towns of the lower watershed.

The Farmington River Coordinating Committee works for the long-term protection of the upper watershed

Sacramento River

The Sacramento River is California’s largest river, beginning its roughly 380-mile journey in the headwaters of the Sierra Nevada before flowing west into the fertile Sacramento Valley and merging with the San Joaquin River in the Sacramento-San Joaquin Delta. The river supports irrigation on 2 million acres in California’s Central Valley and provides key habitat for a diverse range of species, including the imperiled salmon populations that migrate seasonally from the Pacific Ocean. The Sacramento River also provides 35% of California’s developed water supply, helping sustain life in California for the tens of millions who call the state home.

Where is the Sacramento River Located?

Rising in the Klamath Mountains, the river flows south for roughly 380 miles before reaching the Sacramento–San Joaquin River Delta and San Francisco Bay.

Did You know?

The Sacramento River’s watershed is the largest entirely in California, covering much of the northern part of the state, and is home to about 2.8 million people.

The Sacramento River and its valley were one of the major Native American population centers of California. The river’s abundant flow and the valley’s fertile soil and mild climate provided enough resources for hundreds of groups to share the land. Most of the villages were small. Although it was once commonly believed that the original natives lived as tribes, they actually lived as bands, family groups as small as twenty to thirty people. Learn more…

Despite its critical ecological importance, the Sacramento River has been severely degraded over time, with decreasing water quality, rising water temperatures, agricultural diversions, and shrinking habitat for fish and wildlife resulting from intensive development and the comprehensive impacts of climate change. Over a century of levee construction and damming has isolated the river from its historic floodplains, increasing flood risk for downstream residents, eliminating habitat for threatened and endangered species like the precious salmon, and impeding the natural processes that help store groundwater, a perennial problem as the Central Valley has developed into a water-intensive agricultural region. Changing precipitation and weather patterns resulting from climate change are further exacerbating these issues and present a severe threat to the health of the Sacramento River, and the communities and wildlife that depend on it.

Healing the Sacramento means expanding multi-benefit restoration on a regional scale. In the headwaters, this work can take the form of meadow restoration and fire suppression efforts. Down in the Sacramento Valley, restoration includes breaching levees so flows can spread and extensive riparian habitat restoration along the river’s banks. From widespread deforestation in the headwaters to the constriction of the Sacramento River through levees and dams, there is a need for collaboration between environmental advocates, local communities, private landowners, policymakers, and more to bring these ecosystems back into balance and create a sustainable future along the length of one of California’s mighty rivers.

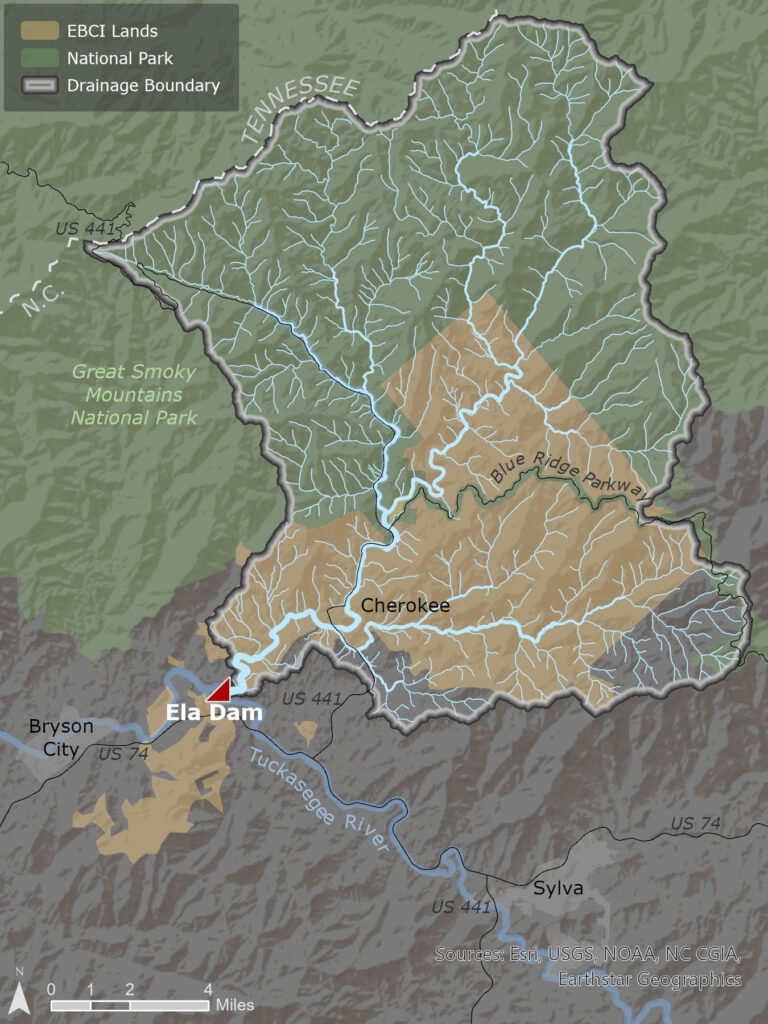

Oconaluftee River

WESTERN NORTH CAROLINA’S ONCE-THRIVING RIVER FOR THE NATIVE CHEROKEE INDIANS

The Oconaluftee River has been part of the culture of indigenous people in what is now called Western North Carolina for thousands of years. It is home to 11 sensitive and rare aquatic species, some of which are only found in a few streams and rivers in western North Carolina.

Stemming from the Great Smoky Mountains, the Oconaluftee River flows south through the Qualla Boundary – reservation land for the Eastern Band of Cherokee Indians (EBCI). The Cherokee people used to rely on the Oconaluftee as a thriving fishery and food source more than 100 years ago before the Ela dam was erected in Whittier, NC, in 1925.

Approximately 18 miles long, the Oconaluftee connects to a much larger river system, feeding into the Tuckasegee, Little Tennessee, Tennessee, Ohio, and Mississippi rivers. Its name is considered sacred by the Cherokee people and was derived from the name of a Cherokee village, Egwanulti. Oconaluftee translates to “by the river” in English.

Finding the Oconaluftee River

An hour west of Asheville, NC, the Oconaluftee River flows across the Blue Ridge Parkway and through the town of Cherokee. Ela dam sits in the town of Whittier, NC, with a population of about 5,000 people. The Oconaluftee provides plenty of opportunities to enjoy river sports such as fishing, kayaking, and tubing in the summer months.

Where is the Oconaluftee River in North Carolina?

An hour west of Asheville, NC, the Oconaluftee River flows across the Blue Ridge Parkway and through the town of Cherokee

Did You know?

The Cherokee people have lived in the Southeastern U.S. for more than 11,000 years and populated land spanning 140,000 square miles in what today encompasses part of seven southern states. As early as 1725 it is recorded that the Cherokee Nation had treaties with the British and began assimilating into European practices and religious institutions.

About the river

Migratory fish species such as Sicklefin Redhorse that once spawned in the upper Oconaluftee River and its tributaries were an important fishery and food resource for the Cherokee people prior to the construction of the Ela dam. Each year, thousands of redhorse fish reach the dam but are blocked from continuing their journey to historic spawning streams.

The construction of Ela dam resulted in a physical and cultural disconnection from a free-flowing Oconaluftee River and resulted in the accumulation of tons of sediment behind the dam. The reservoir, also known as Ela Lake, experiences a reduction in water quality due to the disruption of the natural flow of the river, resulting in increased temperatures, lower oxygenation, and other impacts to water quality indicators.

The benefit of the dam removal to the community and the general public will be fresh, clean, free-flowing water again in the Oconaluftee River.

Stolen Land and the Cherokee Nation

The Cherokee people have lived in the Southeastern U.S. for more than 11,000 years and populated land spanning 140,000 square miles in what today encompasses part of seven southern states. As early as 1725 it is recorded that the Cherokee Nation had treaties with the British and began assimilating into European practices and religious institutions.

By 1825, however, many of the existing treaties with the U.S. had ceded away most of the Cherokee Nation’s once vast lands. In 1838 efforts to displace Cherokees from their land were underway, and an estimated 16,000 people were forcibly relocated to land west of Arkansas. In what was called the “Trail of Tears,” Cherokees and members of other tribal nations were relocated to reservations, many of them dying along the way as they suffered from disease, starvation, exposure to harsh elements, and exhaustion.

During this time of forced migration, the Cherokee tribe was allowed to purchase plots of land for individual households only if they agreed to leave the tribe and become U.S. citizens. Land purchase was otherwise restricted and only allowed for white men. One notable local who befriended and became an advocate for the Cherokee people was William Holland Thomas, who purchased land in North Carolina with his own funds to be used by the Cherokees. Much of this land is now included in the Qualla Boundary. In the late 1800’s the Eastern Band of Cherokee Indians purchased the land adjacent to the Ela dam back from the U.S. government.

Today, the tribe currently occupies the 56,000-acre Qualla Boundary and operates as a sovereign nation with the government headquartered in Cherokee, NC. About 9,000 of the EBCI’s 16,000 registered members live on the Boundary which is situated in Swain and Jackson counties and parts of Cherokee and Graham counties in western North Carolina. There are approximately 400,000 people in the Cherokee Nation across the country.

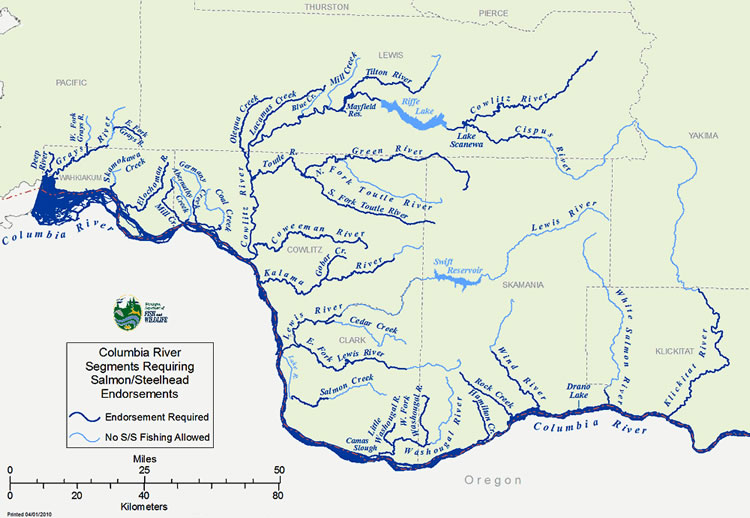

Lewis River

The Lewis River originates from Adams Glacier on 12,280 foot-tall Mt. Adams in southwest Washington state and drains a basin of roughly 1,400 square miles. The river winds its way through scenic Gifford Pinchot National Forest before joining the Columbia River at the Oregon-Washington border between St Helens, OR and La Center, WA.

The Cowlitz, Yakama, Klickitat, and Chinook people have all called the basin home since time immemorial and the river was once home to abundant Pacific salmon, central to their life and culture. The Cowlitz Indian Tribe and Confederated Bands and Tribes of Yakama Nation still steward the river today.

Local communities and visitors to the Lewis River basin enjoy hiking and mountain biking in the lush, forested headwaters, angling for native trout and kokanee in Merwin and Yale reservoirs, and wildlife viewing and camping in the beautiful Gifford Pinchot National Forest. Stretches of the Lewis River near its headwaters form class II – class V+ rapids, providing whitewater opportunities for many.

Lewis River Dams

Today, four major hydroelectric facilities prevent anadromous salmon and bull trout from returning to 170 miles of historical spawning habitat. Constructed between 1931 and 1958, the Lewis River hydroelectric project consists of Merwin Dam, Yale Dam, and Swift No. 1 and Swift No. 2 which are joined by a canal. Cowlitz County Public Utility District owns the Swift No. 2 facility, while PacifiCorp owns Merwin, Yale, and Swift No. 1 and operates all four facilities to produce a total of 580 megawatts of hydroelectricity – enough power to supply approximately 460,000 homes per year. While some salmon not used for broodstocking at the Lewis River or Merwin hatcheries are trapped at the lowermost dam and transported above the uppermost dam by truck, these facilities deny access to traditional spawning habitat for a majority of adult Lower Columbia River salmon and prevent juvenile salmon from outmigrating to the ocean.

American Rivers and 25 other stakeholders – including the Cowlitz Indian Tribe, Yakama Nation, and several state and federal governmental agencies – spent considerable time and energy negotiating a settlement agreement with the utility companies in 2004. This agreement calls for the mitigation of the dams’ impacts by providing upstream and downstream fish passage facilities at each dam. In 2008, the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission authorized 50-year licenses for each of the dams based on this agreement.

The Future

American Rivers, along with many other signatories of the 2004 Settlement Agreement, are working to see this arrangement through. Despite attempts by the utilities to renege on the agreement, the responsibility to restore the Lewis River’s salmon runs remains. The best available science concludes that providing fish passage throughout the Lewis River is a critical action in the recovery of struggling Lower Columbia River salmon and bull trout. Through our active participation in the ongoing discussions between settlement agreement parties, American Rivers stands firm in its assertion that fish passage facilities should undergo immediate construction. We will continue our work with local communities, organizations, and agencies to see this goal of full fish passage realized for the benefit of Lower Columbia River salmon.

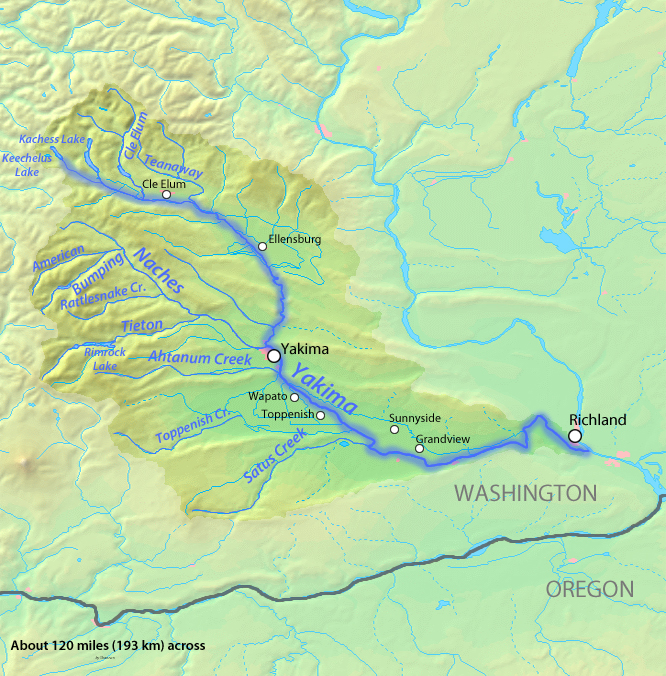

Yakima River

On The Road to Recovery

Raise a glass to the Yakima River. Odds are, you already have, since the premium hops used in most of the nation’s craft beers are one of the major crops sprouting up from the irrigated soil in the Yakima River Valley. Local vineyards are crushing it, too.

That should provide some cheer for the throngs of outdoor recreation lovers from Seattle and the Puget Sound looking to wet their whistles after a day on the playground that surrounds the Yak. From its picturesque headwaters spilling from the national forest in the Cascade Mountains, the 214-mile Yakima combines outstanding opportunities for hiking, skiing, horseback riding, mountain biking, and more with all levels of whitewater paddling and Washington’s only Blue Ribbon trout fishing.

From Keechelus Lake near Snoqualmie Pass, the state’s longest river of origin descends from rugged mountains through a scenic basalt canyon to an agricultural valley floor that culminates in the near-desert steppe at its confluence with the Columbia River. Its upper reaches host large herds of elk and deer and exotic wildlife that includes wolverines, mountain lions, and one of Washington’s newest wolf packs. Downstream, wild trout are the main attraction, but steelhead and salmon are the real story.

Salmon that had been absent from the Yakima River Basin for more than 100 years due to impassable dams are making their return in increasing numbers. Once abundant populations of sockeye salmon have been reintroduced to the Cle Elum River tributary of the Yakima—albeit with the help of a long truck ride from the Columbia—as the initial step in a basin-wide effort to recolonize historic spawning habitat. Plans call for building fish passage where it is currently lacking at Cle Elum Dam, allowing thousands of sockeye, chinook, and steelhead to once again migrate to pristine waters upstream.

Did You know?

Yakima Canyon is home to Washington’s only Blue Ribbon trout stream.

The Tieton River, a Yakima tributary, offers 14 miles of Class III+ whitewater in the late summer, when most surrounding rivers are not flowing.

The highest average flows on the Yakima River (3,542 cfs) are recorded more than halfway up the river at Union Gap.

About 75 percent of the hops in America are grown in the Yakima Valley, along with a good portion of Washington’s apples and cherries.

WHAT STATES DOES THE RIVER CROSS?

Washington

The Backstory

Once a fishery of plenty for the indigenous Yakama people, shortsighted aquatic engineering used to develop the region’s vibrant agriculture industry in the late 1800s led to a collapse of wild salmon in the Yakima and its tributaries. As the ag industry in the otherwise arid valley grew into a $4 billion economy, the lack of fish passage at a series of five irrigation reservoirs decreased salmon numbers from an estimated 800,000 per year to just a few thousand by the 1990s.

American Rivers has joined the Yakama Nation in a fight over fish and water that has gone on for decades. Now climate change is contributing to the battle as a historically reliable snowpack has begun to dwindle. Farmers growing crops in the Yakima Basin face increasing water shortages, while the river’s forested headwaters, already bearing the scars of poor land management, are threatened by new encroachments from human development.

The Future

Partnering with Trout Unlimited, The Wilderness Society, and National Wildlife Federation, American Rivers has been sitting down with stakeholders from the irrigation districts, state and federal agencies, and the Yakama Nation to map out a strategy for restoring fisheries, improving water supply reliability and protecting land for wildlife and the new recreation economy while meeting the challenges of climate change.

The resulting Yakima Basin Integrated Plan has the Cle Elum Dam staged as the first of five dams to be outfitted with fish passage for salmon, jump-starting what could become the largest sockeye salmon run in the Lower 48. Restoration also includes the state’s purchase of more than 50,000 forested acres from a private timber company in the nearby Teanaway River watershed, one of the premier fish spawning and rearing areas in the basin.

Ultimately, the plan aims to establish more than 100,000 acres of public recreation areas that better protect forests and streams, preserve more than 20,000 acres of wilderness areas, designate about 200 miles of new Wild and Scenic rivers, and protect and restore over 70,000 acres of private land currently threatened by development or poor land management.

The goal is to improve water quality and quantity from a modern landscape perspective in order to drive a healthy economy that protects farms, improves fish habitat, and invigorates the basin’s recreational economy. Through balance and innovation, the Yakima River and its tributaries can continue to be a source of beauty, sport, and sustenance for all to enjoy for generations to come.

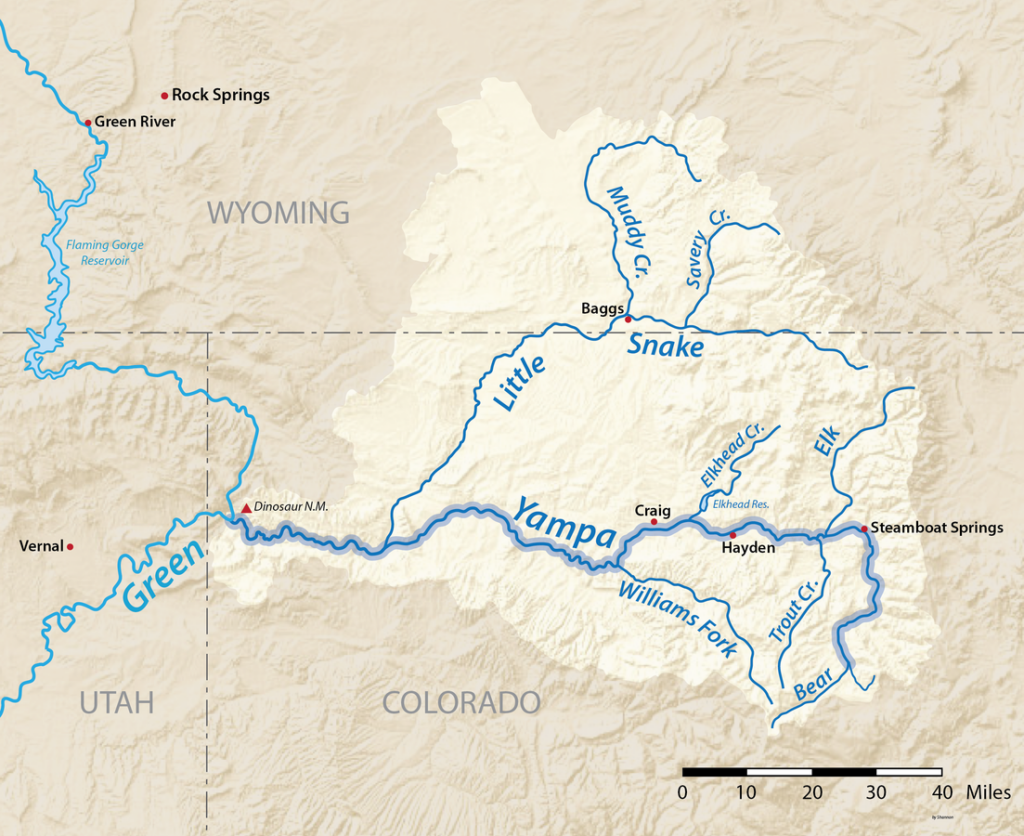

Yampa River

Gorgeous gorges, wild and free

Rising from the Flat Top Mountains in northern Colorado, the wild Yampa River is one of the West’s best floats. It’s a recreational paradise pausing only briefly for a pair of relatively small storage reservoirs high in the basin that spill with spring runoff to retain the character of a free-flowing stream.

As a result, the unregulated Yampa runs free for almost its entire 300-mile journey to Dinosaur National Monument, where it joins the Green River at Echo Park. There it boasts one of the West’s most famous scenic floats at Yampa Canyon, which was the site of one of the nation’s most famous conservation battles when it narrowly escaped being dammed at its mouth in the 1950s. Had that proposed hub of the Colorado River Storage Project succeeded, it would have flooded the Yampa some 45 miles upstream to Deerlodge Park and the Green another 67 miles to Flaming Gorge Dam, and established a dangerous precedent of dam building in a national parks and monuments.

Instead, not one, but two of the world’s greatest multi-day floats remain (Yampa Canyon and Gates of Lodore on the Green). As the river passes through a 2,500-foot cut in the Uinta Mountains, boating Yampa Canyon is more about scenery than whitewater thrills. Rounded buttes and varnished slickrock walls punctuated by towering hoodoos dating back a billion years greet the fortunate few to win launch dates in the annual permit lottery designed to minimize impact to the gorgeous gorge.

More intense whitewater can be found upstream in the Class 4-5 Cross Mountain Gorge or steep tributary creeks feeding the main stem near the resort town of Steamboat Springs, where a playful whitewater park hosts hundreds of kayakers, stand-up paddlers, and inner-tubers throughout the spring and summer. Between the waves, anglers enjoy world class trout fishing meandering through pastoral rangeland and into the rural agricultural towns of Hayden, Milner, Craig and Maybell.

Did You know?

The Yampa River is one of a few river homes to four endangered fishes – the humpback chub, bonytail, colorado pikeminnow, and razorback sucker.

The Colorado pikeminnow can reach six feet long and is one of the world’s largest minnows.

The Yampa provides about one third of Colorado’s contribution to the Colorado River.

The Yampa’s peak recorded flow was 33,200 cfs at Deerlodge Park on May 18, 1984.

WHAT STATES DOES THE RIVER CROSS?

Colorado

The Backstory

Yampa Canyon and Dinosaur National Monument provided the launch site for the river conservation movement when a proposed dam at Echo Park was defeated more than 60 years ago. Today, dam builders are looking farther upstream, including a potential pumpback project that would transfer water across the Continental Divide to quench the thirst of Colorado’s rapidly growing Front Range communities.

Right now, the Yampa provides world-class recreation, is the source of a thriving agricultural economy, serves as the life blood for endangered fish species, and drives local economies from Steamboat Springs to Vernal, Utah. A large-scale diversion would have dramatic impacts on river function all the way to Lake Powell. Not only would it be an ecological disaster for the Yampa and the Upper Colorado River basin, it would cost billions of dollars, putting a huge burden on Colorado taxpayers and water rate payers.

The Future

Beyond the Yampa’s known entities lie several hidden gems. Little Yampa Canyon, Juniper Canyon, and Cross Mountain Gorge have all been determined as suitable for Wild and Scenic River designation by the Bureau of Land Management, prompting the Colorado River Conservation District to abandon conditional water rights for reservoirs that would have flooded those areas. Though still lacking formal W&S designation, they remain free to explore and are often visited by participants in the booming recreation economy surrounding Steamboat Springs.

While water requirements for potential shale-oil development remain a threat in the face of climate change, drought-diminished flows, and warming water temperatures conducive to invasive fish species like smallmouth bass and northern pike, collaborative efforts to protect Yampa River flows continue to succeed. The Colorado Water Trust has leased water from the Upper Yampa Conservancy District to help bolster flows for anglers and tubers later in the summer. And a sincere effort is underway to permanently protect flows required for endangered fish survival in the Yampa by advancing in-stream flow appropriations in the lower reaches through Dinosaur.

Yadkin Pee Dee River

The Yadkin Pee Dee River Basin covers more than 7,200 square miles of the Carolinas connecting the mountains of northwestern North Carolina to the Lowcountry of South Carolina. From its headwaters near Blowing Rock, the Yadkin River flows east and then south across North Carolina’s densely populated midsection. It travels 203 miles — passing farmland; draining the urban landscapes of Winston-Salem, Statesville, Lexington and Salisbury; and fanning through seven man-made reservoirs before its name changes to the Pee Dee or Great Pee Dee River below Lake Tillery. The Great Pee Dee is a free-flowing river for another 230 miles to the Atlantic, leaving North Carolina near McFarlan, meandering through the South Carolina towns of Cheraw and Gresham, and the Waccamaw National Wildlife Refuge and ending its journey at Winyah Bay in South Carolina. It is the principal source of water for the central Carolina region; however, it is threatened by industrial pollution, population growth and poor management.

Since it originates in the Blue Ridge and drains portions of the Piedmont, Sandhills and Coastal Plain, the Yadkin Pee Dee River Basin contains a wide variety of habitat types, as well as many rare plants and animals. The basin’s rare species (including endangered, threatened, significantly rare or of special concern) include 38 aquatic animals. Two species are federally listed as endangered — the shortnose sturgeon, a migratory marine fish that once spawned in the river but has not been spotted in the basin since 1985; and the Carolina heelsplitter, a mussel now known from only nine populations in the world, including the lower basin’s Goose Creek. Five new species, all mollusks, have been added to the state’s endangered species list — the Carolina creekshell, brook floater, Atlantic pigtoe, yellow lampmussel and savannah lilliput.

Forests cover half of the basin, including the federal lands of the Pee Dee National Wildlife Refuge, the Blue Ridge Parkway, Uwharrie National Forest and the Waccamaw National Wildlife Refuge which lies completely within the basin. Most of the watershed’s forestland is privately owned though. Nearly one-third of the watershed is used for agriculture, including cropland (15.6 percent) and pastureland (14.1 percent). Just 13 percent of the land is developed, although this figure is rising rapidly.

The Backstory

The Yadkin Pee Dee River provides residents and visitors with a host of benefits, including scenic views, recreational and economic opportunities, clean drinking water and floodwater storage. However, the river and riverside lands that provide these values are at risk due to population growth and poorly planned development. Increasing water demand has led to more competition for the limited water resources available while outdated water reclamation facilities are causing unnecessary spikes in pollution. Riverside forests are also being cleared to make way for new development and forest products which increases polluted stormwater run-off that contaminates streams and pose challenges to drinking water treatment. High Rock Lake- south of Winston-Salem, NC- experiences dangerous and unnatural algal blooms due to the poor water management system in the upper portion of the river. Logging operations for wood pellet production have decimated wetlands critical to filtering pollutants out of stormwater and absorbing floodwaters. Additionally, numerous large and small dams clog the river disconnecting the natural flow through the system. These issues are exacerbated by the prolific growth of underregulated poultry farms that have questionable waste management strategies around water protection.

The Yadkin river has been significantly impacted by numerous dams built on it. The uppermost reservoir is W. Kerr Scott Reservoir. The southern portion of the Yadkin has been impounded by a chain of six reservoirs: High Rock, Tuckertown, Badin (Narrows), Falls, Tillery and Blewett Falls. The first four built in the first half of the 20th century to power Alcoa’s aluminum smelters and later two were built to provide power to the region. High Rock is the first and largest of the Yadkin chain lakes. Badin, the oldest, was built in 1917 just below the gorge called “the Narrows” to power an aluminum plant in Badin. Alcoa’s smelting operations have been closed in NC and Cube Hydro now operates those dams to sell power and Duke Energy is licensed to operate the other two for its electric utilities. The Pee Dee River is then free flowing through South Carolina to the ocean.

The region is also experiencing impacts from climate change. Frequent flooding has caused damage to infrastructure and loss of property. The frequency and intensity of storm events are expected to escalate as climate change causes greater hurricane activity and associated rainfall. Drought conditions have also affected natural and human communities in the basin. Combined, these changes are exacerbating existing water quality and quantity issues in critical habitats along the river, posing greater treatment challenges for the region’s utilities, and creating financial burdens for local governments, families and businesses.

Looking to the Future

The development pressures in the watershed require better water management. The upper portion of the Yadkin River is sandwiched between development occurring in Winston-Salem and the growth of Charlotte. In the lower portion coastal development is pushing into the floodplain endangering critical habitats, threatening water quality and placing infrastructure, homes and businesses in harms way. Investing in the protection and restoration of these rivers and riverside lands is a cost-effective and sustainable solution to these pressing climate and growth challenges and will ensure that they are preserved for generations to come.

Efforts that are designed to protect and restore rivers should center the voices of communities who are most impacted rivers and river-related decisions. Communities advocate for their rivers when they are connected to their rivers. Whether those connections include recreation, subsistence, advocacy, environmental education, sustainable economic development or other activities, communities should be supported in connecting to their local rivers in ways that address their needs, values and interests.

Collaboration between diverse partners including community leaders, local governments, conservation organizations and businesses is needed to build the financial support, knowledge, natural infrastructure, policies and community capacities needed to promote equitable watershed management strategies that safeguard clean water and build resilience for people and wildlife.

The growing communities of the watershed should look to use water management strategies that find the full value of water- such as an integrated water management or One Water approach. These strategies define the value of the natural landscapes and utilize water management strategies that mimic the natural processes- like green stormwater infrastructure and floodplain restoration.

The relicensing of the Cube Hydro and Duke Energy projects were completed between 2010 and 2018 and the projects will be improving their water quality and land protection investments in the coming years over the course of the license.

The poultry operations in the watershed continue to grow and more oversight is needed to ensure that ecological damage is avoided and sustainable agricultural operations are encouraged in the watershed.

White Salmon River

Wild Fish and Scenic Whitewater

Few things in life can top the intoxicating thrill of riding a whitewater raft or kayak down glacial runoff pouring from the flanks of a 12,000-foot volcano. Yet, in 2011, the White Salmon River found a way.

That was the year demolitions experts blew a gaping hole in the base of the 125-foot tall Condit Dam and reconnected the entirety of the White Salmon to the Columbia River, allowing the return of the once-abundant runs of wild salmon and steelhead that had provided physical, spiritual, and cultural nourishment to local Native American tribes. As an added bonus, the dramatic dam removal extended the whitewater thrill ride another five miles downstream, carrying paddlers all the way to the Columbia River Gorge National Scenic Area.

Not that the White Salmon is lacking for scenery in its own right. This iconic southwest Washington river flows from the snowy slopes of Mount Adams for 45 miles, more than 25 of which are federally designated as Wild and Scenic. The steep, breathtaking canyons and crystal clear water help drive a robust tourism and recreation industry around the river nationally recognized as a premier whitewater destination.

Ten outfitters run commercial trips on the river, and at least 25,000 boaters use the White Salmon each year, bringing an important economic influx to the local community. Paddlers now floating past the former dam site struggle to recognize the plug was ever there.

Did You know?

In addition to salmon and steelhead runs, the White Salmon is among the top three resident rainbow trout fisheries in the region.

The White Salmon offers Class III-IV whitewater in a natural setting that remains runnable virtually year-round.

At 12,307 feet, Mt. Adams (headwaters of the White Salmon) is the second highest peak in the Pacific Northwest after Mt. Rainier.

Condit Dam was the largest dam ever removed in the United States until the Elwha Ecosystem Restoration Project on the Olympic Peninsula removed the larger Elwha Dam and Glines Canyon Dams.

WHAT STATES DOES THE RIVER CROSS?

Washington

The Backstory

Built in 1913 to generate hydropower, Condit Dam was an important part of the history and development of the area. But the benefits came at a high cost. The towering dam disrupted natural river flows and was built with no fish passage, limiting salmon and steelhead to the lower three miles of river.

Condit ultimately created more ecological problems than it did electricity (an average of just 10 megawatts) and soon outlived its usefulness. Faced with the mounting costs of operating the aging dam, owner PacifiCorp signed an agreement in 1999 with diverse interests including American Rivers, the Yakama Indian Nation, government agencies, and other partners to remove it.

When the hole was blasted in Condit’s base in October 2011, the reservoir behind it drained in a matter of hours. Today, salmon have returned to historic upstream spawning grounds on the free-flowing river and the number of whitewater paddlers visiting the White Salmon continues to grow.

The Future

With the White Salmon once again flowing freely into the Columbia River, migrating salmon and steelhead have only the Bonneville Dam just downstream from the confluence to overcome. Bonneville does include fish ladders, although the large concentration of salmon awaiting their opportunity to swim upstream now attracts several California sea lions who prey on the fish. The dam has also blocked the upstream spawning migration of white sturgeon, although they still spawn in the Columbia River below Bonneville.

In 1986, the lower White Salmon between Gilmer Creek and Buck Creek earned Wild and Scenic designation, followed by a longer segment of the upper river between the headwaters and the boundary of the Gifford Pinchot National Forest in 2005. Further support for the Wild and Scenic campaign will help keep development threats in check and ensure the river will remain in its relatively pristine state for generations to come.