It’s Time to Amend the Wild and Scenic Rivers Act to include Tribal River Protections

Tribes should be able to manage Wild and Scenic Rivers on their lands.

A co-published blog by American Rivers and the Getches-Wilkinson Center at Colorado Law.

The Wild and Scenic Rivers Act of 1968 has been the preeminent tool to protect free-flowing rivers in the United States since it was passed more than 50 years ago. Under the Act, rivers with “outstandingly remarkable scenic, recreational, geologic, fish and wildlife, historic, cultural or other similar values,” as well as their immediate environments, are protected from dams and other potential harms. In spite of its success, the Act largely omits Tribes, failing to give Native Nations the authority to designate, manage, and co-manage Wild and Scenic rivers within their own boundaries and on ancestral lands. Correction of this omission is long overdue, both in terms of equity and the long-term benefit to rivers.

A current example of this omission was brought to our attention through conversations with Indigenous community members along the Little Colorado River (LCR) in Arizona. The LCR was threatened in recent years by a series of pumped-storage hydropower projects proposed on Navajo Nation lands by non-Indigenous developers, and against the will of the Navajo Nation, Hopi Tribe, Pueblo of Zuni, and others who find the LCR culturally important. Historically, under the Federal Power Act, proposed hydropower projects have been given a preliminary permit on tribal trust lands by the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission (FERC) against the will of the Tribe whose land the projects would be located on. Indigenous community advocates understandably wanted to know, “What can we do to permanently protect the Little Colorado River from these unwanted hydropower projects?”

Designating a river under the Wild and Scenic Rivers Act is a powerful defense against unwanted dams and diversions–it is the only designation that prevents new dams and diversions on designated rivers. The problem is that since Tribes were largely omitted from the 1968 Act, they were not given the power to designate or manage Wild and Scenic rivers, even on their own lands. That management power currently defaults to the National Park Service, even when a designated river is on tribal lands. To say that this is a disincentive for Tribes to utilize the Wild and Scenic Rivers Act to protect their rivers is an understatement.

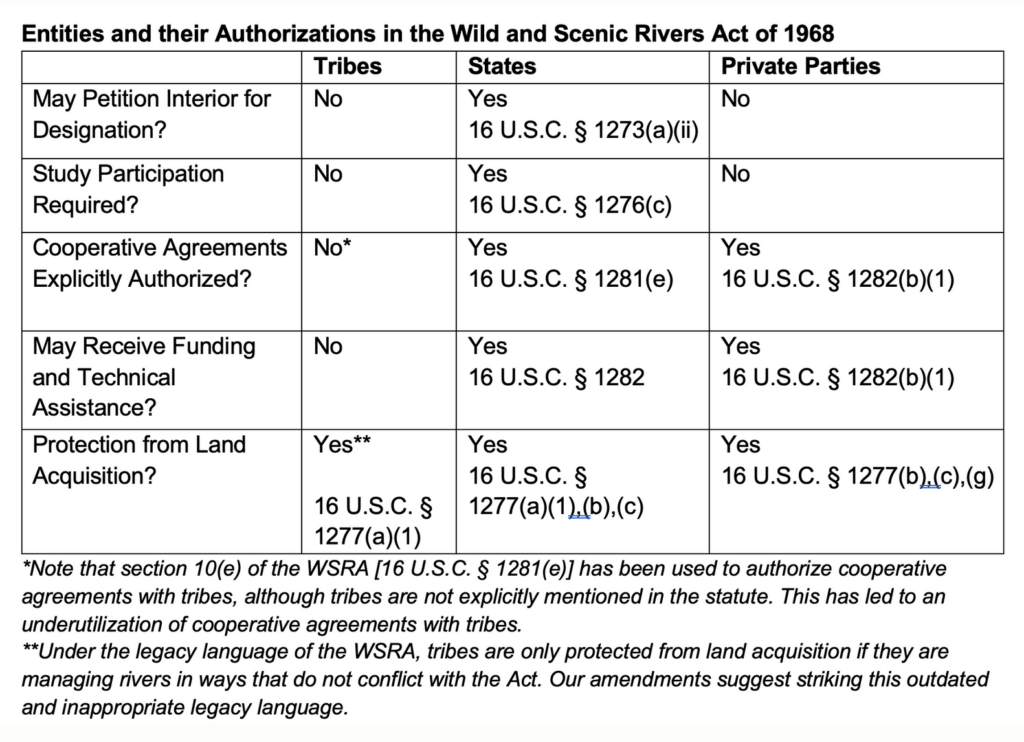

And that’s not all. As the Table below shows, Tribes don’t even have some of the powers that have been given to states and private parties under the Act, such as the ability to petition the Secretary of Interior to give Wild and Scenic protections to state-protected rivers, or the ability to receive funding and technical assistance, which both private parties and states can. Co-management/co-stewardship agreements and cooperative agreements are also not explicitly authorized for Tribes in the Act, which is a potential disincentive for federal agencies to explore such agreements with willing, interested, and knowledgeable Tribes.

As sovereign nations, Tribes should at least have the power that states and NGOs have regarding river designations. Tribes should be able to manage Wild and Scenic Rivers on their lands, ask the Secretary of Interior to include rivers protected by Tribes under the Wild and Scenic Rivers Act, be formally authorized to engage in co-stewardship agreements with federal agencies, and have the ability to receive funding and technical assistance when managing rivers on their lands.

Correcting the omission of Tribes in the Wild and Scenic Rivers Act remains long overdue. We heard from both legal scholars and tribal communities that creating a well-researched, draft proposal—which you can download here—would be the best way to begin an informed conversation. This is in no way intended to be a finished product, but meant to engage Tribes, advocates, and legal thinkers in what might be possible, and in turn help us make that a reality.

We also realize that proposing to amend a bedrock natural resources law is no small undertaking, and not without some risks. The structure of the Wild and Scenic Rivers Act makes amending the Act easier and less risky than amending other similar laws. Currently, each new river designation is added to the National Wild and Scenic Rivers System through an amendment to the original Act, which means that a new Wild and Scenic designation by a Tribe that includes these proposed amendments would be all that would be necessary to implement them. Furthermore, the Concept Paper proposes extending existing authorities to Tribes through the addition of new sections in the Wild and Scenic Rivers Act, not changes to existing protections that have been settled law for over 50 years.

In this way, and with your help, we not only propose to retain the protections that the Wild and Scenic Rivers Act has afforded outstanding free-flowing rivers across the county for the last half century, but to expand the ability for Tribes to utilize those same protections to safeguard free-flowing rivers of cultural and ecological importance into the future. Now is the time to address the omission of Tribes in the Wild and Scenic Rivers Act and other bedrock natural resources laws. Doing so would be a measure of restorative justice, while also benefiting Tribes and all life which depends on rivers.

Please download and read the Concept Paper and Draft Model Legislation, and let us know what you think. We look forward to hearing from you.

Click HERE to download a PDF of the Concept Paper and Draft Model Legislation. Please send feedback, questions, and comments to info@tribalwildandscenic.org or through our website www.tribalwildandscenic.org.

The Wild and Scenic Rivers Act Amendments Project was founded in 2021 by American Rivers, the Grand Canyon Trust, and the Getches-Wilkinson Center in response to Indigenous advocates seeking a tool to protect culturally and ecologically important rivers on Tribal lands from FERC-licensed hydropower projects. More input from Tribes, river advocates, and legal scholars is being sought for the next phase of this project.

3 responses to “It’s Time to Amend the Wild and Scenic Rivers Act to include Tribal River Protections ”

Needed action. Only official laws can save our environment.

Needed!!

Maybe rather than opening up a can of worms by amending the act it would be better to simply pass a carbon copy of the act that applies to tribal lands and puts the tribes in the management position.