Understanding the Menominee Tribal Perspective on the Back 40 Mine

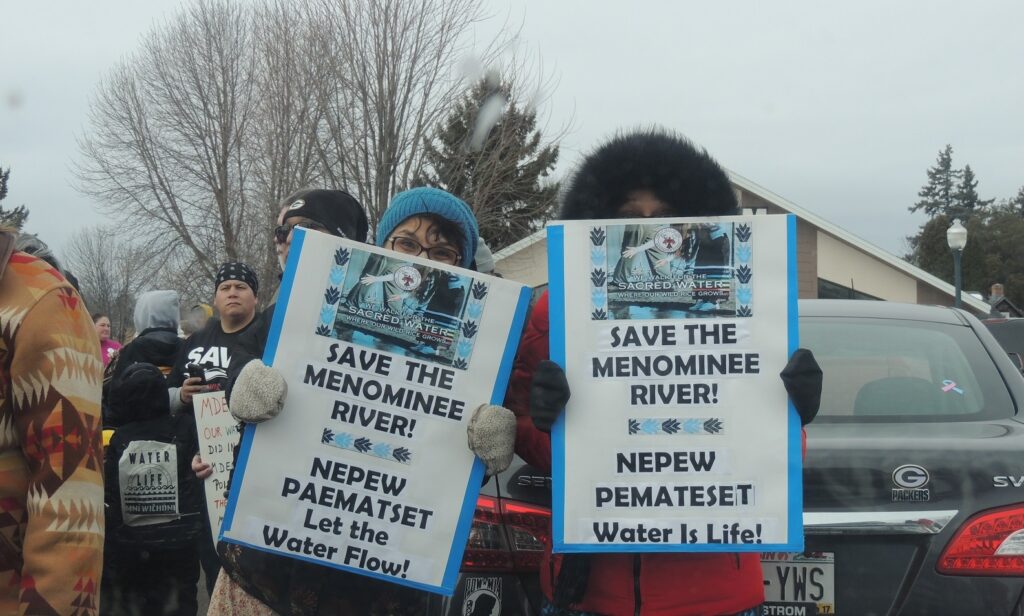

In our blog series about the Menominee river and opposition to the Back Forty mine, advocates for the Menominee Tribe are speaking up to protect their sacred land.

This guest blog by Anahkwet/Guy Reiter is a part of our America’s Most Endangered Rivers® series on the Menominee River in Wisconsin and Michigan.

First, I would like to acknowledge my ancestors, who endured so much so that we could have what we have today. I’m forever in your debt. Waewaenon Ketaenon (I say thank you)!

Posoh, Anahkwet newiswan, Wapaesyah netotaem. My name is Guy Reiter, and I just introduced myself in my Menominee language. My elders taught me to always introduce myself and my clans before I speak to a new audience.

It’s hard for me to write down what I want to say because I value the spoken word over the written word. So I’m going to write as if I’m sitting with you speaking.

My Tribe, the Menominee Indian Tribe, is the longest living inhabitant of this land that is called Wisconsin. Like most Tribes in America, we’re one of the most studied peoples on the planet. Our beginning as a Tribe begins a mere 60 miles northeast of our current reservation at the mouth of the Menominee River. The city of Marinette, Wisconsin, now lies on that sacred site. Our oral history states that this is the place where our creation began thousands of years ago.

In order to know my Tribe, you have to start with the creation of my Tribe. This creation story can be looked up on the internet or in a book (just take care to remember that the people writing the story were using translators, and a number of things can get lost in translation). The Menominee Creation Story was told to me by one of our elders on the reservation when I started to organize against the Back Forty Mine. We, Menominees, were given the responsibility to look after that river and land by the creator thousands of years ago, and that supersedes any treaty or law. (This article isn’t designed to inform of our whole history, it’s just giving you a very small piece.)

The Menominee River is a part of me; its essence is within my soul. There isn’t a Menominee Indian around who wouldn’t feel connected and unified standing next to the river while gazing upon its sacred banks and water.

If a mine were to pollute the Menominee River, worse than what it already is, it would devastate my fellow Menominees and I. Putting a mine on this location is just the same as if they were to drill for oil in the Garden of Eden. Imagine what people would say when asking them to describe how it feels to see this mine polluting their sacred area.

Not only that, but to ask people to go to meetings and draft up comments in order to try and let people understand how this project affects them on a much deeper level.

Ask people to try and hold back tears when decision makers who don’t have the same connection to that sacred area tell about how they’re going to protect it better than ever before, how the technology has changed so much in the last few years, and that the mine will have a minimal impact upon the environment. When these decision makers explain how they’re going to issue a permit, and that permit will protect the river, land, plants, insects, animals, and my antiquity, my sacred area.

Will that permit bring comfort to my ancestors who have dwelt in that ground for time immemorial? Will that permit comfort the animals that will be displaced from their homes? Or the plants and insects? I don’t think so.

Who’s going to tell the whole of creation that calls this place home not to worry about the pollution? That the few jobs this mine will produce will be good for the communities living there? That somehow, this project will pull their respected communities out of their current economic crisis? They may not be able to enjoy the land, or drink the water, but at least they’ll have jobs…?

I was asked at a speaking event to introduce myself, and I said I was from the “Tribe of Barely Making It, but We’re Making It.” I would challenge any other group of people in America to endure what we First Nations endured, and be able to still hold on to their language and culture. We, First Nations people, are a part of this land, and our languages and cultures were born and bred here. We have always been here and we always will be. Our communities are abundant in strength and have determination to not give up; our old people taught us that. We will continue to resist colonialism for our next seven generations, so relatives in the future will understand that our languages and cultures will keep them grounded, determined and strong. We, First Nations, already underwent drastic climate changes and survived.

To whomever is reading this, as your eyes fall upon my last sentences, I want you, for a moment, to close your eyes and take a deep breath. Do you feel that? Do you feel the connection? Do you understand how sacred creation is? It’s made up from the same stuff as you and I are made of. We need to start to rebuild our relationship with our mother earth again. Let’s stand together and speak up for the voices who cannot speak for themselves, like the plants, animals, birds and insects. Let’s remember that we are a part of this land and not separate from it.

Let’s join our collective voices together and tell our leaders that we are no longer going to stay silent while our precious mother earth gets abused. Let’s tell them that we are going to reclaim our humanity and once again establish our connection with creation.

I’ll stand with all colors and creeds who value our mother earth and that have the courage to shoulder the responsibility that it’s going to take. I want to say waewaenon for taking the time out of your life to read this.

Anahkwet, also known as Guy Reiter, is a MENOMINEE NATION organizer and advocate.

2 responses to “Understanding the Menominee Tribal Perspective on the Back 40 Mine”

With a quickness supporting the movement and reject the proposed Back Forty Mine.

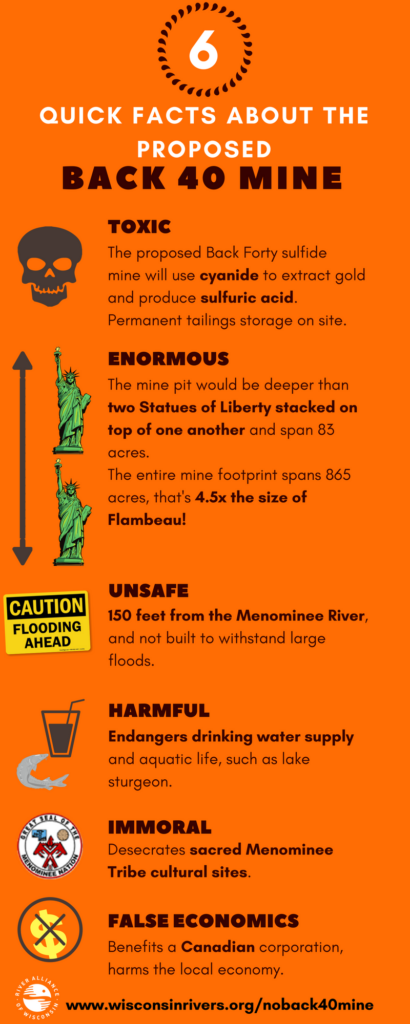

I, Lori Paitl, am personally asking the Michigan Department of Environmental Quality to reject the pending wetlands permit and prevent the establishment of the proposed Back Forty Mine, 150 feet from the banks of the Menominee River in Stephenson, Michigan.