River basins don’t get much more complicated than the Colorado – seven states, two countries, 30 Tribal nations, 11 National Parks, and a $1.4 trillion economy span its 247,000 square mile reach, not to mention the countless species of wildlife that rely on the river and its tributaries. Yet, while not perfect, the management of the Colorado River Basin is guided by “The Law of the River,” a series of agreements, treaties, and a few court cases meshed together to keep the peace. For more than 100 years, managers of the Colorado River, including the Basin states of Arizona, California, Colorado, Nevada, New Mexico, Utah, and Wyoming, along with the Federal government, have worked together to manage the river with varying degrees of success.

However, a critical set of rules for how the river is managed is set to expire at the end of this year, and with warming temperatures, unpredictable precipitation, and a growing population across the Southwest all contributing to diminished river flows, the need for new guidelines is urgent. In times of crisis, the states and federal government have been forced to forge short-term, often emergency agreements to conserve water and prevent the system from crashing overall. And for the past two years, negotiators have been working to determine new guidelines for how states and the federal government will manage water shortages and reservoir levels after 2026. A final plan for the new guidelines must be in place by October 2026, when the new “water year” starts and the implementation of the current rules expires.

Last summer, in an attempt to encourage further collaboration and progress, the Department of the Interior set a deadline of November 11, 2025, for the states to come to an agreement. Despite deliberate, concerted effort right up to the deadline, the states have not reached consensus on a path forward. This stalemate is very concerning, as the communities, economies, and ecosystems that rely on the river need certainty around how the system will be managed as we prepare for a hotter, drier future. Management decisions must be grounded in sound science, investments in on-the-ground projects must be made, and efforts to build resilience in communities and ecosystems and expand conservation across the Basin must be pursued. Further, we must ensure that Tribal voices are included in decision-making and that any decisions prioritize the health of the river itself. When we don’t consider the needs of the river, everything else that depends upon it is at risk.

So, where are we now? In a joint statement, the Basin states and the federal government committed to keep striving to reach a consensus, and we applaud their efforts and determination to keep at it. We strongly encourage the states to remain at the table in a spirit of collaboration and shared sacrifice, and the federal government to continue its leadership to hold the process together.

Time is of the essence as the river can no longer sustain all the demands expected of it while we engage in inter-basin political squabbles. Like any complex negotiation, there must be a spirit of honest give and take, with the truest of intentions to find a holistic solution for the river. The river needs flexible tools, inspired solutions, and long-term investments to help communities, agricultural interests, and Tribes prepare for the impacts of drought while ensuring comprehensive water security. And ultimately, we must remember the river when it comes to forging these agreements and reducing risk to the system overall. There is no time to waste – we must act now to sustain the Colorado River.

The Uncompahgre River flows from Colorado’s San Juan mountains through the towns of Ouray and Ridgway and then into Ridgway Reservoir, which stores water for farms and households downstream. The river is beautiful, but also troubled; runoff from old mines carries heavy metals into the river, and it is pinched into an unnaturally straight and simple channel as it passes from mountain canyon headwaters into an agricultural valley.

As the river moves through the modified channel, it carves deeper into the valley floor and less frequently spills over its bank. As a result, the local water table has dropped, and riverside trees such as cottonwoods have died, impoverishing this important habitat. Water users on the Ward Ditch at the top of the valley were also struggling with broken-down infrastructure, making it difficult to access and manage water for irrigation. This confluence of challenges created a landscape of opportunity for the Uncompahgre Multi-Benefit Project, which addresses environmental problems along the river and water users’ needs, while also improving water quality and reducing flood risks downstream.

The Project, managed by American Rivers, took an integrated approach to restoring a one-mile stretch of the river, which included replacing and stabilizing the Ward Ditch diversion, notching a historic berm to reconnect the river to its floodplain, and placing rock structures in the river that both protect against bank erosion and improve fish habitat. Meanwhile, ditch and field improvements make it easier to spread water across the land for agriculture and re-establish native vegetation.

In addition to the direct benefits this project delivers for on-site habitat and landowners, the enhanced ability of the river to spread out on its floodplain, both through the ditch diversion and natural processes, also provides downstream benefits. As the water slows and spreads across the floodplain during high flows, its destructive power to erode banks and damage infrastructure downstream is diminished. The same dynamics enable pollutants and sediment from upstream abandoned mines or potential wildfires to settle out before the river flows into the downstream reservoir.

With construction wrapping up in November 2025, the transformation of this stretch of river and its adjacent floodplain is nearly complete. Fields of flowers and fresh willow plantings are replacing invasive species and dead cottonwoods, and new pools, sandbars, and riffles are providing instream habitat, complementing other organizations’ work to remediate old mines upstream. As a bonus, when the water level is right, the reach has become an inviting run for skilled whitewater boaters.

The Uncompahgre River Project would not have been possible without the close collaboration of local landowners, the Uncompahgre Watershed Partnership, the support of the Ouray County Board of County Commissioners, and generous grants from the US Bureau of Reclamation, the Colorado Water Conservation Board, and Colorado River District. American Rivers and our partners are hopeful that this project will inspire other water users downstream to undertake similar projects to keep the momentum going and bring renewed vitality to the entire upper Uncompahgre River and surrounding agricultural lands.

I’m resisting making an analogy between these river critters and the children’s story about the three little pigs. Okay, having just written that, I guess I’m not doing so well there….

One of the many things we have learned over the decades working to make our rivers, streams, lakes, and wetlands healthy and full of life again is that some of the smallest and least conspicuous river critters can play an outsized role in this work.

Readers of this blog may recall the piece on the algae species Cymbella back in 2024 and what this microscopic diatom tells scientists about river health. The caddisfly is another one of these clean water workers who has something to tell us.

The anglers among us may already be thinking ahead and guessing that what the caddisfly has to say is something like “I know how to help you catch that brookie” as a dry fly lure on the end of their line. True enough, angler friends.

But there’s a bigger and more powerful message coming from this taxonomic Order (Tricoptera), the largest group of aquatic insects. While the caddisfly does go through a complete metamorphosis and eventually emerges as a terrestrial flying insect, its more interesting phases are the aquatic ones. The common defining attribute of the caddisfly is its ability to generate silk. These hard-headed (literally), antenna-less critters use that silk in savvy ways to build sophisticated and wildly creative homes.

While these insects are small, it’s easy to see their home-building skills if you look closely in a small stream. The many different species of caddisflies have adapted to different aquatic habitats, so you can find them from still pools to quickly rushing riffles. In those quiet pools, they will use their silk to construct homes from leaves or small sticks and twigs. One of the important jobs of the caddisfly is helping to decompose organic matter in streams. While building homes with this organic material, they also shred leaves and twigs with their strong jaws, which contributes to the cycling of freshwater nutrients. To see these leafy homes in pools, look for small collections of shredded leaves and twigs in a gossamer web of silk.

Where water is flowing faster over cobble and gravel bottoms, you will find them nestled into tubular homes made of small stones with just their tough little noggin poking out the end! They collect these stones and artfully build a snug tubular home cemented together with their silk. You can find these sturdier homes by gently turning over rocks and seeing these small structures, usually less than an inch, attached to the underside of the rock.

So there goes the three little pigs analogy – leaves, sticks, and stones – for the straw, wood, and bricks! I know, I know. Kinda like a dad joke…

But back to their clean water work. Most of the different species of caddisflies are sensitive to water quality conditions, particularly the amount of dissolved oxygen in the water. When the dissolved oxygen is low due to increased temperatures or too many nutrients in the water, they are not able to survive. This characteristic is used by aquatic scientists to monitor the health of rivers and streams in ways that are much more powerful than occasionally taking a measurement of dissolved oxygen with a meter or chemical test.

How so?

For over 30 years, scientists have been assembling groups of aquatic organisms – algae, bugs, and fish – and grouping them according to their tolerance for different conditions of pollution. Some river critters are very tolerant of low dissolved oxygen or turbidity, or other chemical conditions, some are not. The caddisfly larvae are important members of these groupings of indicator species.

By creating these groupings based on extensive monitoring and statistical analysis, a robust predictive model is created and used to understand how our work to improve and protect water quality is doing.

So if we watch which critters are living where, they can tell us if a stretch of river is getting healthier with much more certainty than a simple measurement of dissolved oxygen, turbidity, or pH.

Here’s to another clean water worker helping us all to enjoy what our rivers and streams give us all!

A version of this blog was first published in Estuary, a quarterly magazine for people who care about the Connecticut River; its history, health, and ecology—present and future. Find out how you can subscribe at estuarymagazine.com.

Visitation on Montana’s Wild and Scenic Flathead River has grown significantly in the last five years. Yet, just one river ranger remains to steward 219 river miles and 29 river recreation sites following recent federal government workforce reductions. More people coupled with fewer Forest Service staff has residents wondering how the agency and the community will protect the river’s health now and into the future.

Birthplace of the Wild and Scenic Rivers Act

The Flathead Wild and Scenic River includes the North, South, and Middle Forks that ultimately join and flow into the north end of Flathead Lake. A dam proposed on the Middle Fork of the Flathead River within the Bob Marshall Wilderness was the inspiration for the Wild and Scenic Rivers Act of 1968, which preserves free-flowing rivers and their outstanding values. The three forks of the Flathead River were designated as Wild and Scenic in 1976.

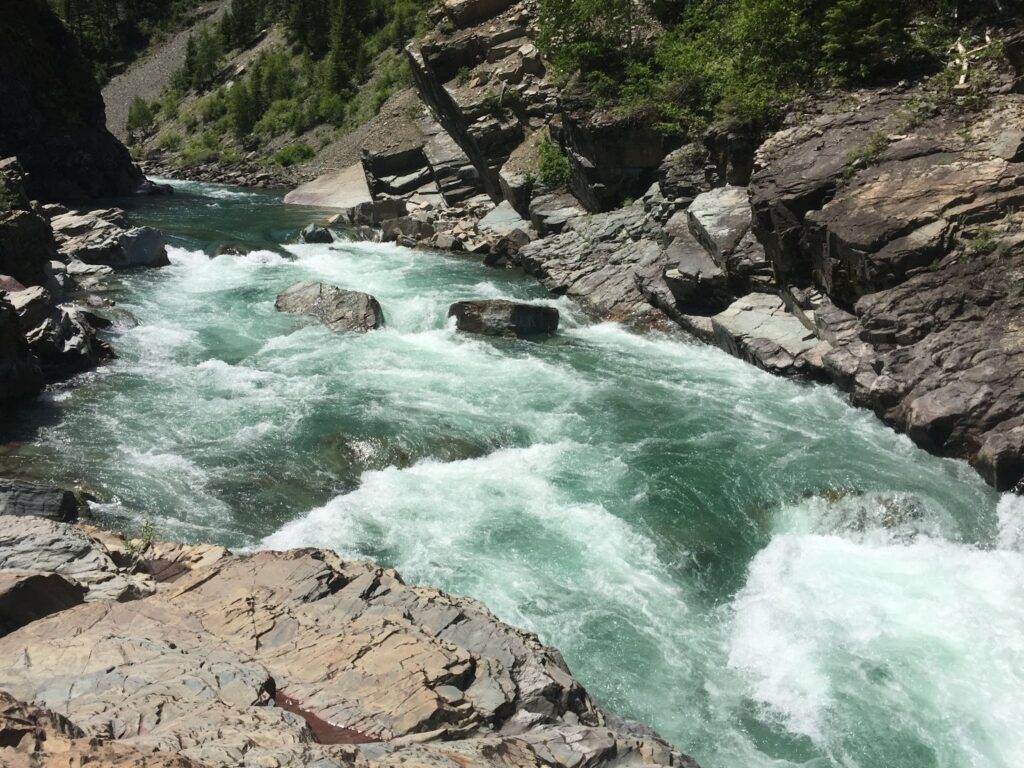

Renowned as having the cleanest, clearest water in Montana and beyond, the three forks of the Flathead River are a recreation destination featuring whitewater rapids, scenic floating, a healthy native trout fishery, and unparalleled riverside camping. The Flathead River system is the backbone for a robust tourism economy: Fifteen percent of tourism dollars coming into Flathead County are spent by visitors on outfitters and guides.

Shared Responsibility for the Future

There’s no doubt Montanans and tourists alike love the Flathead River. However, the recent federal employee reductions in force, together with increasing river use, belie a delicate tension between the benefits of loving this river and the consequences of loving it too much to the point of overuse. Loving a place too much can look different in different places: hordes of RVs parked on beaches, long waits at boat ramps, overflowing parking lots, erosion on river banks or human waste.

When impacts from river recreation reach a boiling point, we all share in the responsibility to protect river health. Regardless of staffing constraints, the Forest Service is required to act. Part of what’s needed is a transparent menu of actions–from staggering boat launch times to requiring human waste packout–that the agency can choose from to lessen recreation impacts while still providing access to the river.

Partners and outfitters can and do help as well. And they’re needed now more than ever, with more staffing reductions predicted across the federal government. Each year, Flathead Rivers Alliance mobilizes 300 volunteers contributing more than 1,700 volunteer hours, distributes 4,000+ reusable cleanup bags, and collects litter from 80 miles of river, manages volunteer river ambassadors to educate river visitors on how to Leave No Trace, conducts noxious weed pulls on 40 miles of river, and monitors water quality. This summer, river outfitters also helped to keep bathrooms and river access sites clean, work that was formerly done by the Forest Service.

While we need more public-private partnerships to extend agency capacity, it’s critical that the Forest Service take proactive actions to prevent impacts from overcrowding, pollution in the form of trash and human waste, streambank erosion, and overfishing on the river, despite staffing shortages.

How You Can Engage

You can join American Rivers and Flathead Rivers Alliance in asking the Forest Service to put the appropriate safeguards in place to ensure we love the Flathead River responsibly. Assuming the process remains on track, concerned community members will have an opportunity this winter to give the Forest Service feedback on their proposed management plan for the Flathead Wild and Scenic River. The plan should set science-based thresholds on river use, commit to monitoring river health and visitor experiences, and creatively forge partnerships to monitor and enforce needed changes to visitation timing, location, extent, and behaviors, now and in the future. Montana, and the nation, have only one Flathead River. As the new management plan for the river is crafted, we must put the health of the river first.

Follow announcements by the Flathead National Forest on the Flathead River Comprehensive River Management Planning Process, sign up to volunteer with Flathead Rivers Alliance, and contact Montana’s congressional delegation to share your concerns about impacts to the Flathead River from federal government workforce reductions.

Bob Jordan serves as President of the Flathead Rivers Alliance Board of Directors and Sheena Pate serves as Executive Director. Lisa Ronald is an associate conservation director with American Rivers in Western Montana.

The Yakima River Basin in Central Washington is experiencing one of the worst prolonged droughts in modern history. American Rivers visited our partners in the Yakima Basin Integrated Plan to witness the river and better understand the drought’s impacts on the fish, farms, and communities it supports.

Photographer David Moskowitz was able to help capture the story through the incredible images seen below.

Of all the signs that something is wrong—the curling leaves of stunted crops, the multiplying mats of river stargrass, the tense expressions of water managers—nothing tells the story of this drought like standing on the dry, hard bed of a drastically receded reservoir.

Between 1910 and 1933, the U.S. Bureau of Reclamation built five reservoirs to harness water for Washington farms and towns in the 6,000-square-mile Yakima Basin. Together, Kachess, Keechelus, Cle Elum, Bumping, and Rimrock store about one million acre-feet of water.

But not this year.

By September 2025, capacity was a mere 20%. That’s the lowest level since recordkeeping began at the reservoirs in 1971, marking a historic water shortage.

There simply wasn’t enough snowpack in the Central Cascades to fill the reservoirs in early 2025, leaving them with just 35% of the water they usually store at that time of year. Additionally, winter and spring rainfall was well below normal in the mountainous catchment in western Yakima County.

On April 8, this reality led the Washington Department of Ecology to declare that the upper Yakima, lower Yakima, and Naches watersheds had officially crossed into their third consecutive year of a severe drought.

What happens—or doesn’t happen—with stored water in the upper basin sends huge ripples downstream to the Yakima River and its tributaries.

Irrigation districts that rely on human-made diversions in the river have been struggling to supply enough water to a $4.5-billion agricultural industry. Junior water rights holders, such as Roza Irrigation District and Kittitas Reclamation District, have strategized on the best ways to ration their reduced allotments—just 40% of the full amount they are generally entitled to—throughout the hot summer months of 2025.

“We’re running the canals the lowest we ever have,” says Sage Park, policy manager for Roza. “Our growers are facing a very hard time, with bad water supplies on top of bad markets.”

Some farms have gone out of business, confirms Jim Willard, owner of Willard Farms and Solstice Vineyards near Prosser, when we stop by. But he is hanging on. Willard established his farm in 1952, which means he has weathered the drought years of at least 1977, 1993, 1994, 2001, 2005, and 2015.

How does the current year compare?

“It’s another lousy drought,” Willard shrugs. “You know what you’ve got to do, the decisions you’ve got to make to keep the farm viable into the future.”

“The fish are always in drought,” Joe Blodgett, manager of Yakama Nation Fisheries, says matter-of-factly as soon as we meet at the Wapato Dam on the lower Yakima River.

The last significant drought in 2015 hit out-migrating juvenile salmon hard. Warm, shallow river water reduced their numbers from 1 million to 200,000. The fishery is still recovering—and now, another major drought.

Joining Blodgett is his team of engineers and scientists, who are dedicated to restoring habitat, improving fish passage, and growing and releasing hatchery salmon, bull trout, and lamprey to bolster drastically declining numbers.

The Yakama Nation’s connection to native fish species in the basin traces back thousands of years. The salmon trade was the first economy of the basin, and that link remains critical to the tribe’s identity and cultural and economic survival today.

A little downstream, a small fishing scaffold protrudes into the river—a reminder of a bygone era long before the dam, and a symbol of the harvestable and sustainable future the Yakama Nation’s 10,000 members envision returning to.

One day. After the drought breaks.

Until then, the fisheries team is preparing with an ambitious plan to update the ailing Wapato Dam, built in 1917, and construct modern fish passage to improve survival rates.

“Each species has a story to tell,” Blodgett says, smiling, as we part ways for today.

Even in drought, the Yakama Nation and the irrigation districts, conservation organizations, and government agencies that make up the Yakima Basin Integrated Plan collaborate to increase flows of cool river water that fish need to survive.

Maybe it’s truer to say especially in drought.

That collaboration is unique in the West. It extends to a multitude of projects, many costing tens of millions of dollars, to modernize aging infrastructure, protect and restore fisheries and river habitat, improve water supply reliability, and store more ground and surface water.

“This is a terrible drought,” says Brandon Parsons, American Rivers director of river restoration. “But we’d be in a lot worse shape if we hadn’t made years of prior investments in the river. We have to continue to work together and implement projects if we’re going to lessen the impacts of more droughts like this.”

People in the basin know more frequent and severe droughts are on the horizon. They’re racing to ready the region and keep it habitable in a rapidly changing world. Families, fish and wildlife, business and agriculture—all life depends on the Yakima River’s ability to provide clean, cool, reliable water into the future.

American Rivers recognizes the power of getting out and being on the rivers we are called to protect. Just as we need those rivers for our survival, the rivers need us, too.

When the federal government recently withdrew from a historic partnership known as the Resilient Columbia Basin Agreement, we knew it was time to take to the river once again to chart our path forward. We helped the Nez Perce Tribe lead a team of 17 Tribal representatives and multiple state legislators, congressional staff, and non-profit partners on a five-day Snake River trip through Hells Canyon, on the border of Oregon and Idaho. During this impactful trip, the group discussed current challenges and the historical context that brought us to this point, and brainstormed solutions for our region’s future.

Convening in Idaho: Day 1

After everyone arrived in Lewiston, we met up with EcoFlight to get an aerial view of the river and the surrounding landscape. We flew over the confluence of the Snake and Clearwater Rivers, through golden dryland wheat fields as far as the eye can see, and over Lower Granite Dam, where we spotted a lone wood products barge waiting at the lock for passage downriver.

Our group then joined the festivities at Hells Gate State Park, where groups were preparing food, art, and music for a “Free the Snake” flotilla the following day.

Not long after arrival, we all went to bed to get ready for our early flight to meet our river guides in Halfway, Oregon, for our descent through the deepest gorge in North America.

On the river: Day 2

After a safety talk the next morning, our giddy group began our four-day, three-night journey downstream. With the launch dock still in sight, we landed a rainbow trout on the first cast – clearly a good omen for the trip to come.

Our first lunch stop offered a warm welcome to Nimiipuu country from our gracious Nez Perce hosts, where we were grounded in creation stories and the importance of salmon, who represent the “first treaty” of a sacred promise between the animals and the Creator to care for the Nimiipuu people.

We took turns sharing who we were, where we came from, and our intentions for this experience.

After an easy day on the water in bright blue paddle rafts and sporty inflatable kayaks, we spotted a round black bear on the hillside, right above our camp. While our guides prepared dinner, a lively game of UNO sent laughter into the canyon, and the first of several sturgeon fishing efforts got underway.

After a bit of fun, it was time to get to work. We had an in-depth conversation about the Columbia River Basin, which included the health of the fish that depend on it and the results of our conservation efforts. We used clothing props and home-laminated maps to aid the conversation, which continued through dinner and dessert, until the darkened canyon told us it was time to go to sleep.

On the river: Day 3

Day 3 started with early morning conversations about regional energy needs over camp coffee. To advocate responsibly for breaching the four hydroelectric dams on the lower Snake River, we need to co-create clean energy alternatives that consider impacts to Tribes.

Lunch was dedicated to learning about first foods and seasonal rounds. Tribal members generously shared their histories and ties to place, how important their traditional foods are to their culture and well-being, and how each Tribe and place are unique.

After paddling through Wild Sheep and Lower Granite rapids, most of our crew beat the heat by jumping in the water to float the remaining distance to our second camp. Our group had found the river magic!

Although this camp is technically called Oregon Hole, I will forever remember it as Sturgeon Hole. Since we were skunked the previous night, I wasn’t holding my breath that we would land a fish. A little later, while I was setting up my tent at the edge of the campground, I heard hoots and hollers and immediately knew what was happening – we got one!

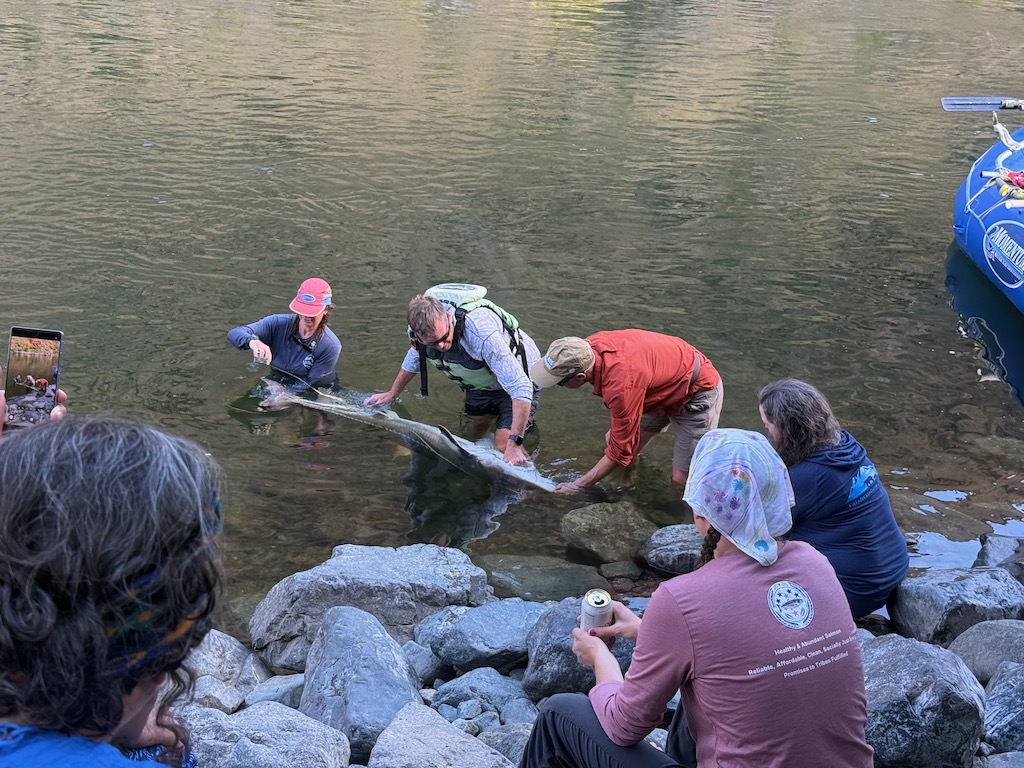

My good friend, Rein Attemann, had reeled in a six-foot sturgeon! The fish was in the water, upside down, while a Nez Perce biologist evaluated her and explained her physiology to the captive group.

Like sharks, sturgeons are mostly made of cartilage, and flipping them upside down induces a trance-like state called “tonic immobility”. In this state, the fish becomes calm, allowing them to be handled gently before being released.

After dinner, we heard the second sturgeon line ping and several of us raced down to the water. I was keen for this experience and had bought a fishing license in Halfway. It took me a few tries to develop a rhythm, and reeling in this fish was no easy task, but as she got closer to the boat, I could see she was beautiful, mysterious, and massive – like a living dinosaur.

At 7.5 feet in length, she was likely at least 50 years old, making her bigger and older than me. She was probably alive before some (or all) of the four lower Snake River dams were constructed. She had a Floy tag, which meant she had been caught before. We wrote down the numbers to report to Idaho Fish and Game, turned her right side up, and released her to power downriver.

On the river: Days 4 and 5

Our last full day and a half on the river was filled with deeper conversations about how to develop a truly just energy transition in the Northwest, in partnership with Tribal Nations, and how to face opponents and stakeholders who resist the restoration of the Snake River and greater Columbia Basin.

Our time was also punctuated by play and laughter – it’s important to have fun and take care of each other along the way.

Being on the river brings out the most intense and authentic version of who people are. It allows relationships and conversations to progress at warp speed relative to what is possible in the normal course of our work. I returned home confident and knowing that this group can do hard things. We will keep up the momentum, keep supporting each other, and continue to have the hard conversations – preferably on the river!

Construction and revegetation at Ackerson Meadow are complete, and now it’s time to let nature do the work it does best! This marks a huge milestone in the movement towards headwaters restoration in California’s Sierra Nevada, with the Ackerson restoration standing as the largest full-fill meadow restoration in the Sierra Nevada and the largest wetland restoration in Yosemite National Park’s 135 years. When meadow restoration began as a practice in the Sierra roughly 45 years ago, a project of this size was a pipe dream for restoration practitioners, with significant hurdles to funding, permitting, and cross-agency collaboration standing in the way. But now, 150,000 cubic yards of soil and 434,000 wetland container plants later, water is flowing across the entirety of this fully restored meadow. Now the project’s partners, Yosemite National Park, Stanislaus National Forest, Yosemite Conservancy, American Rivers, and anyone who values clean water, healthy rivers, and thriving wildlife can celebrate.

The work at Ackerson is a gift that will keep on giving to generations of recreators, wildlife enthusiasts, and downstream water users. The benefits of restoring mountain meadows are both significant and wide-ranging, and a restored meadow has a sort of multiplier effect on the surrounding landscape and watershed. A healthy, fully restored Ackerson is projected to store 70.8 million gallons of groundwater each year, or enough water to satisfy the daily use of almost 250,000 households, while filtering out pollutants before flows enter the South Fork Tuolumne River. Of course, California is known as a global biodiversity hotspot, and Ackerson Meadow is home to nearly 60 species of birds and provides refuge for threatened and endangered species such as the Little Willow Flycatcher, Great Grey Owl, and northwestern pond turtle.

But Ackerson is also a gift for scientists and agencies who want to see this sort of work fine-tuned and expanded. We will monitor the site over the coming years, and the findings will feed into this ‘meadow movement’ organized by the Sierra Meadows Partnership, as we quantify the benefits of restoration: hydrological changes, soil carbon sequestration, and habitat recovery for endangered species.

Outside of the direct benefits to rivers, ecosystems, and the scientific community, Ackerson is both a milestone and a launching pad, setting the table for expanded public-private partnerships with the federal land management agencies and nonprofit conservation organizations. Through our years of project management, we demonstrated how a nonprofit like American Rivers can bring technical expertise, fundraising capacity, and the flexibility to achieve conservation outcomes in short order. These partnerships and this project have shown not only the power of collaboration across different sectors, but also how a common vision can be approached from different angles, leveraging our collective expertise to the benefit of the communities we live in, the wildlife we cherish, and the rivers that are the lifeblood of California.

August 29th, 2025, marks 20 years since Hurricane Katrina hit the Gulf Coast. While Katrina was a category 3 hurricane when making land fall, the flooding and destruction after the storm far outweighed the initial impact.

In these 20 years, we have learned a lot about the challenges with levees and the importance of healthy, connected floodplains. Our Senior Director of Floodplain Restoration, Eileen Shader, reflects on these lessons and how state and federal governments can act to prevent that scale of destruction from happening again.

What can you do to help?

Take action: Tell states they must step up to make sure they are investing in floodplain management and floodplain reconnection and flood safety, and that that they have the rules and regulations in place to help guide local government and local decisions about where we develop and how we develop in floodplains to keep people and property safe.

The view downstream from here

A few short weeks ago, public lands and the rivers that flow through them were spared from a disastrous sell-off provision in a massive tax and spending bill. Victory was snatched from the jaws of defeat because of the nationwide bipartisan public outcry against the proposal from supporters like you.

But what happens now? Will there be more backroom deals and bills in the future that attempt to sell them off? Will there be attempts to enable misuse of public lands — effectively bulldozing America’s backyard and playground of regular people like you and me? You bet. Such proposals are like weeds — you can count on them sprouting up again and again. This is because influential special interests, from multinational mining conglomerates to big polluters, are always looking for schemes to get rich quick. The only remedy is to remain on guard, ready to defend against these bad ideas whenever they re-emerge. Or is it?

Defending existing protections is an essential part of protecting America’s rivers. Policies like the “Roadless Rule” protect critical conservation areas from new roads and timber clear-cutting. The pollution standards in the Clean Water Act keep harmful cancer-causing chemicals out of your drinking water. But these common-sense policies are under attack — whether it be by outright repeal, rescission, or by failure by agencies to do their job. And while a country must defend these protections, it shouldn’t stop us from seeking new ones. As the saying goes, “the best defense is a good offense.”

Communities across the country, and across the political spectrum, are proactively taking steps to protect their rivers and the values they provide as sources of drinking water, and as cherished places to hunt, fish, float, swim, and a multitude of other uses.

The many braids of a protected river

There is no one-size-fits-all solution for how to protect a river. Effective protection mechanisms vary across the country. The diversity of mechanisms to protect rivers is emblematic of American ingenuity — where there is a will to protect a river, we always find a way.

Here are a few examples to showcase the diversity of proactive river protection approaches happening right now across the country at the federal, state, and local levels.

Federal

With so many threats occurring at the federal level to public lands and the agencies entrusted to manage them, one could be forgiven for assuming that positive proactive action to protect rivers would be put on hold. Not so. For example, Republican Congressman Vern Buchanan from Florida recently sponsored and passed the Little Manatee Wild and Scenic River Act to provide comprehensive and permanent legal protection for Florida’s cherished Little Manatee River. Florida Republican Congressman, Rep. W. Gregory Steube, and U.S. Senator Rick Scott each introduced another Wild and Scenic River bill to protect the Myakka River in Sarasota County, while Rep. Ryan Zinke just introduced a Wild and Scenic Bill to protect nearly 100 miles of the Gallatin and Madison rivers in Montana. And thanks to bipartisan action in Georgia, the Ocmulgee River could soon receive permanent protection as America’s newest national park and the first co-managed by a tribal nation in the region.

Many other examples exist, from coast to coast, but we often don’t hear much about them, because the good news of “offense” for rivers is all too often drowned out by noise from battles to defend existing protections. But the lesson is clear: ongoing bipartisan grassroots efforts to protect rivers remind us that protecting rivers is not a red or blue issue; it is a red, white, and blue issue.

State

States and municipalities across the country have passed their own zoning ordinances to create buffers that conserve land along rivers. Known as riparian areas, the trees and vegetation along the banks are the proverbial lungs of a river, allowing it to breathe and filter nutrients to maintain the healthy water quality we need to drink, fish, and swim safely. The State of New Jersey is just one example of a state taking action to protect rivers through riparian buffers.

The state passed legislation that created rules for establishing and maintaining riparian buffers statewide. As a result, the state of New Jersey has one of the highest rates of protected rivers in the country. Other states from Pennsylvania, to Minnesota, to the state of Washington have all proactively established their own systems for establishing and maintaining riparian buffers.

Another recent inspiring example of new protections for rivers at the state level comes from Alabama. In response to a groundswell of local public support, a coalition of local grassroots organizations successfully petitioned the Alabama Environmental Management Commission to update and strengthen clean water standards across the state. The Commission voted 6-1 in favor of the petition. The change will result in limiting the maximum allowed amounts of 12 toxic and cancer-causing pollutants, including cyanide, hexachloroethane, and 4-trichlorobenzene, in rivers across the state. The change will undoubtedly save lives and improve public well-being.

Local

Recognizing the importance of clean, reliable, safe drinking water to the city’s future, Raleigh, North Carolina, developed its own comprehensive watershed protection plan to protect rivers that supply drinking water to that community.

The protection plan involves land acquisition and conservation easements to protect private lands in the watershed. To date, the program has protected over 10,000 acres of land and 177 miles of streams. The protection program is self-sufficient, funded by a watershed protection fee of 11¢ per 100 cubic feet of water used. For the average residential customer, this equates to a charge of about 60¢ per month on their water bill — a fee far lower than would be required to fund the extra water treatment costs if the protections were not in place. Not only does Raleigh’s watershed protection program provide water security and create spaces for parks and recreation, it also saves its customers money and avoids the need for new taxes.

Local utilities and municipalities spanning red and blue states across the country from Texas to Arkansas to Ohio and New York and many others are implementing similar programs to protect rivers supplying drinking water to that community.

Any way you look at it, river protection pays off with a great return on investment for all of us.

Taking initiative

No matter where you live, your voice matters in keeping rivers healthy. It is essential to prevent backsliding from the protections we as a country worked so hard to achieve. We don’t want to see a return to the days when rivers like the Cuyahoga literally catch fire due to the level of pollution. Rivers are essential to life, liberty, and pursuit of happiness to all Americans. People from all different backgrounds and affiliations understand this and are mobilizing to protect rivers across the country.

As the examples above show, this is because the people understand that taking action to protect rivers and the public lands they flow through is indeed a red, white, and blue issue — not a red or blue issue. So regardless of your political affiliation, regardless of where you live, and regardless of your background, please don’t let your eagle’s eye for defense keep you from going on offense to protect what matters to you.

The One Big Beautiful Bill Act (OBBBA), also known as H.R. 1, is now law. Signed by President Trump on July 4 after months of intense negotiations, its path was anything but smooth. The legislation advanced through a fast-track process known as reconciliation, which allows members of Congress to bypass the typical 60-vote threshold in the Senate and pass bills with a simple majority in both chambers.

After passing the House, the bill moved to the Senate. Earlier this month, after substantial changes to the bill, the Senate passed H.R. 1 by a 51–50 vote, with Vice President J.D. Vance casting the tie-breaking vote. Three Republicans joined all Democrats and Independents in opposing the bill. Just 48 hours later, the House narrowly approved the Senate-amended bill by a vote of 218–214. All Democrats opposed the measure, joined by Republicans Thomas Massie of Kentucky and Brian Fitzpatrick of Pennsylvania.

The following analysis observes three ways in which the OBBBA presents modest opportunities and potential challenges for Western water infrastructure.

Revitalizing Western Water Infrastructure

Section 50501 authorizes and appropriates $1 billion to enhance conveyance facilities and improve surface water storage under the Bureau of Reclamation, which primarily operates in the West. Notably, this funding waives any reimbursement requirements or cost-sharing to states and tribes—offering a direct investment in Western water systems. Projects may include retrofitting dams like Shasta Dam for improved salmon migration, upgrading Colorado River facilities for greater efficiency, and addressing groundwater challenges.

While this funding provides a boost, it also raises concerns. Prioritizing the modernization of aging infrastructure without equal emphasis on long-term watershed health and public welfare could pose risks. And while $1 billion sounds substantial, it must stretch across 13 states with extensive and expensive needs—posing clear limitations.

Expanding Hydropower and Grid Reliability

Sections 70512 and 70513 preserve tax credits for hydropower operators to upgrade facilities, improve dam safety, and modernize equipment—all of which help bolster grid reliability and reduce service disruptions. More efficient systems and expanded storage capacity can lower energy costs while supporting river restoration efforts.

In 2024, the Department of Energy awarded up to $430 million in incentive payments to 293 hydroelectric projects across 33 states, aiming to improve both performance and environmental standards. While outdated dams that are no longer in use need to come down, others continue to provide needed energy. Many of these hydropower facilities are over 80 years old and in critical need of modernization.

However, these tax credits are not permanent. They expire at the end of 2036, creating urgency to complete upgrades within a limited window. Strengthening agency guidance will be essential to ensure these improvements deliver lasting ecological and operational benefits.

Boosting Conservation Tools for Farmers

Section 10601 strengthens the USDA’s voluntary conservation partnerships by expanding long-term funding for key programs like EQIP, CSP, RCPP, and ACEP. These initiatives support farmers and ranchers in adopting practices that enhance soil health, water quality, and wildlife habitat—often benefiting rivers and streams as well. By adding resources to the Farm Bill’s permanent funding baseline, the OBBBA ensures more stable, long-term support for sustainable land and water management.

The bill also allocates $150 million to the Small Watershed Program (PL-566) to support flood control, watershed rehabilitation, and retrofitting or removal of outdated dams. These investments improve community resilience, reduce downstream flood risk, and restore river connectivity. Beginning in FY 2026, the bill also provides $1 million annually for the Grassroots Source Water Protection Program, which supports locally driven efforts to safeguard drinking water sources through upstream conservation.

These measures expand the conservation toolkit significantly. However, existing programs—though effective—are often oversubscribed and challenging to access, especially for small-scale farmers. Streamlining application processes and increasing technical support will be key to ensuring access.

What Happens Now

Looking ahead, American Rivers will work closely with federal agencies—including the Departments of the Interior, Agriculture, and Energy—to recommend projects that upgrade infrastructure, protect rivers, and enhance aquatic and riparian habitats. These efforts will improve how water is captured, stored, and delivered across communities.

Meanwhile, Capitol Hill is already discussing the possibility of another reconciliation bill. We’ll continue monitoring legislative developments and will keep our partners informed of opportunities to engage and advocate for smart, sustainable water policy.

President Trump signed the One Big Beautiful Bill Act (OBBBA) into law on July 4th, 2025. The legislation passed both chambers of Congress after narrow, party-line votes and reflects major Republican priorities in tax policy, energy development, immigration enforcement, and regulatory rollback. Senate Majority Leader Thune delivered the bill to the White House just in time for the President’s Independence Day deadline, with Vice President J.D. Vance casting the tie-breaking vote in the Senate.

Recapping the top 5 Final Provisions

- Environment and Public Works

- Section 80151: “Project Sponsor Opt-In Fees for Environmental Reviews”

- Creates an opt-in fee program at the Council on Environmental Quality for expedited environmental reviews under the National Environmental Policy Act.

- Section 80151: “Project Sponsor Opt-In Fees for Environmental Reviews”

- Commerce, Justice, and Science

- Section _0008. “Rescission of certain amounts for the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration”

- Rescinds unobligated balances of the Inflation Reduction Act’s 40001 (coastal communities and climate resilience), 40002 (marine sanctuaries), 40003 (permitting, planning, and public engagement), and 40004 (research and forecasting weather).

- Section _0008. “Rescission of certain amounts for the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration”

- Energy and Natural Resources

- Section 50501: Reclamation Infrastructure Improvements- Subtitle E “Water”

- Authorizes $1 billion from the U.S. Treasury (FY2025–FY2034) for the Secretary of the Interior to enhance existing conveyance and surface water storage facilities managed by the Bureau of Reclamation.

- Funds are not subject to reimbursement or cost-sharing, offering direct investment in western water infrastructure.

- Section 50501: Reclamation Infrastructure Improvements- Subtitle E “Water”

- Agriculture

- Sec.10601. “Conservation”

- Increase baseline mandatory funding for four working lands programs (ACEP, CSP, EQIP, and RCPP)

- Provides $150M for the Small Watershed Program, commonly referred to as PL-566.

- Provides $1 million for the Grassroots Source Water Protection Program starting in fiscal year 2026.

- Rescinds unobligated balances of IRA funds within the four working lands programs.

- Sec.10601. “Conservation”

- Finance

- Sec. 70512. “Phase-out and restrictions on clean electricity production credit.” & Sec. 70513. “Phase-out and restrictions on clean electricity investment credit.”

- Wind and solar tax credits are phased out completely by 2027.

- 100% of the clean energy production tax credit (45Y) and clean energy investment tax credit (48E) are available only for hydropower, geothermal, and nuclear facilities if they start construction in or prior to 2033, then step down to 75% in 2034, 50% in 2035, and 0% in 2036.

- Sec. 70512. “Phase-out and restrictions on clean electricity production credit.” & Sec. 70513. “Phase-out and restrictions on clean electricity investment credit.”

Analysis

The bill’s water infrastructure provisions, including $1 billion in direct funding for Bureau of Reclamation facilities, could benefit western water delivery systems. However, without environmental safeguards or restoration priorities, these investments may have limited or even negative downstream impacts on river health.

The OBBBA sharply prioritizes tax breaks, fossil fuels, manufacturing, land privatization, and border enforcement while rolling back IRA-era investments in climate resilience and clean energy. While indeed some Farm Bill conservation programs see modest funding boosts and tax credits for hydropower are extended through 2036, these are outweighed and overshadowed by sweeping rescissions and divestments.

Regrettably, the legislation leaves rivers and river-dependent communities behind, exposing them to greater risks from pollution, flooding, drought, and other extreme weather disasters. It falls far short of addressing today’s urgent water security and infrastructure needs. Although the public lands sell-off pieces were ultimately removed, the attempt itself – combined with deep cuts to IRA-backed programs – sends a clear message: river restoration and climate resilience may not be receiving the level of attention and investment needed at this time.

The bill’s winners are defense industries, big banks, traditional energy producers, real estate developers, and high-income taxpayers. Its losers include Medicaid beneficiaries, clean energy industries, nonprofit and environmental sectors.

Next Steps

With the bill now enacted, the federal agencies will begin implementation immediately. Legal and environmental challenges are likely, especially around rescissions and Medicaid work requirements. The bill’s wide-ranging impacts are expected to shape national policy debates through the 2026 midterms and beyond.

Helpful Resources

The legislative text of the final bill is roughly 900 pages and was modified throughout the legislative process. For more detailed information, utilize these resources in addition to the summary of relevant public health provisions below.

- Full Text — H.R. 1

- Congressional Budget Office — Information Concerning the Budgetary Effects of H.R. 1, as Passed by the Senate on July 1, 2025

- Council of Economic Advisors – Legislation for Historic Prosperity

- Evergreen Action – Memo on H.R 1

World Nature Conservation Day is July 28. It is more important than ever to speak up and make your voice heard for our nation’s rivers. We know there is a lot going on in the world that can make it overwhelming to figure out what you can do to help. That’s why we’ve put together 5 simple things you can do this World Nature Conservation Day to make an impact in your community and nationwide:

1. Take Action: Sign our Clean Water Petition

Investing in clean water security generates a tremendous return on investment for the country. Clean water is not a luxury. It is vital to our future economic growth and essential to the heritage of our communities. Please ask your member of Congress to support this common sense blueprint for keeping America’s rivers safe and our water clean.

2. use our official handbook to organize a river clean up

If this is the first time you are hosting a river cleanup, download this one-stop-shop handbook on how to organize a successful event. It has everything you need — from tips on how to select a cleanup site to engaging your volunteers to securing attention from local media. Organize a river clean up in your community today!

3. Advocate for rivers through our action center

Be a voice for rivers: Last year, our community sent 30,000+ messages to decision-makers calling on them to take action for healthier rivers and cleaner water. Check out our Action Center and take action today!

4. Learn about the top 10 ways to conserve water at home

There are a few simple things you can do at home — Fix leaks, turn off the faucet while brushing your teeth — to ease the burden on your local water supply and save money in the process. These water-saving measures can have a big impact on water demand in your local community.

5. Share your favorite river!

Leave a comment here and share your favorite river and why you love it. If someone else has mentioned your river or a river you love, share your story with them. We are all connected by our waterways, let’s prove it!

One small action each day adds up to make a big impact over time. Share this list with your family and friends and revisit these actions when you can. Healthy rivers are for everyone, not just a privileged few. We are in this together, and it will take all of us in this movement to protect rivers and preserve clean water.