Restoring floodplains — the low-lying lands next to rivers — is one of the most effective ways to reduce flood risk to communities, strengthen ecosystems, and improve water resources.

Across the country, communities, Tribes, and land and resource managers are working to restore rivers and reconnect floodplains. As weather events grow more intense and unpredictable, these projects are becoming more essential. Floodplains are a powerful and natural form of infrastructure. When floodplains are healthy and connected, they can absorb and slow floodwaters, recharge and store groundwater, reduce wildfire impacts, improve rangeland health, and increase biodiversity. Healthy floodplains can protect communities while also strengthening ecosystems.

Despite the proven benefits, floodplain restoration projects are often delayed or stopped entirely because of outdated policies from the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA). Why? Because…

Outdated policies treat restoration like development.

Under current FEMA policy — even when projects pose no risk to people or property — river and floodplain restoration is regulated the same as new development. In other words, projects designed to reduce flood risk can get caught up in FEMA’s no-rise standard and Conditional Letter of Map Revision (CLOMR) process. The no-rise standard is meant to prevent floodplain development from increasing flood elevations and putting people or property at risk.

The thing is, restoration projects — such as reconnecting floodplains to rivers, planting riparian vegetation, or stabilizing streambanks — can lower long-term flood risk. The lack of distinction between restoration and development creates unnecessary roadblocks, slows urgently needed resilience work, and discourages restoration efforts that could help communities adapt to worsening floods.

So what can be done? Enter:

Floodplain Enhancement and Recovery Act

The Floodplain Enhancement and Recovery Act would modernize FEMA’s approach to ecosystem restoration.

If passed, the Floodplain Enhancement and Recovery Act would give states and local communities more flexibility under FEMA’s “No- Rise” rule to execute projects needed to restore these natural floodplains. Passing this act would reduce regulatory burdens and give states, Tribes, and local communities the tools they need to restore floodplains, protect lives and property, and build safer, more resilient landscapes.

The Floodplains Enhancement and Recovery Act would ensure that floodplain restoration is treated like what it is — an investment in safety and resilience — not a risk.

So don’t wait, follow the link below to tell Congress to support the Floodplains Enhancement and Recovery Act now!

In December of 2025, a hodge-podge, high-power mix of water users, water managers and policy makers, non-profits, scientists, and journalists convened in Las Vegas for the 80th annual Colorado River Water Users Association Conference (CRWUA) in Las Vegas. The conference, and the open and closed-door meetings it hosts, was themed “forging a path forward”. Insofar as forging is an act of hammering and compression, the theme was almost too on the nose with states having missed a November 11 deadline for agreement on future management of the Colorado River, and is now facing a new deadline looming on the horizon of 2026. It was a fitting culmination of a complicated year on one of the world’s hardest-working rivers, where drought and demand have stretched already thin supplies to the brink. The economies and cultures of nearly 40 million people hang in the balance of the ongoing negotiations, as does the health and future of the river itself.

2025 on the Colorado River…

This past year was chock-full of high-profile meetings between the principals of the seven Colorado River basin states working to negotiate a path forward for management of the Colorado River. American Rivers participated in collective action and influence on the next generation of rules, called “Interim Guidelines.” Critically, we worked with partners to provide a science-informed Cooperative Conservation Alternative that prioritized the health and long-term viability of the river alongside community, economic, and cultural needs. While it’s been rebranded in the federal government’s latest document as the “Maximum Operational Flexibility Alternative” (we’ll get into this more below), the Alternative remains one of five under consideration.

Originally faced with a November 11, 2025, deadline for agreement, the upper and lower basin states failed to come together with a shared vision for the future of the Colorado River. We worked with partners to both pressure and support the principles working to find an agreement.

We leveraged the power of storytelling to encourage those determining the future of the Colorado River to prioritize the river itself. Our newest film collaboration with Fin & Fur Films, The American Southwest, aired in more than 70 theatres during a 40-day theatre run in the West, and inspired thousands to take action on behalf of the river. We hosted and spoke on panels to help audiences understand the significance of a very wonky process and know how to direct their energy to action.

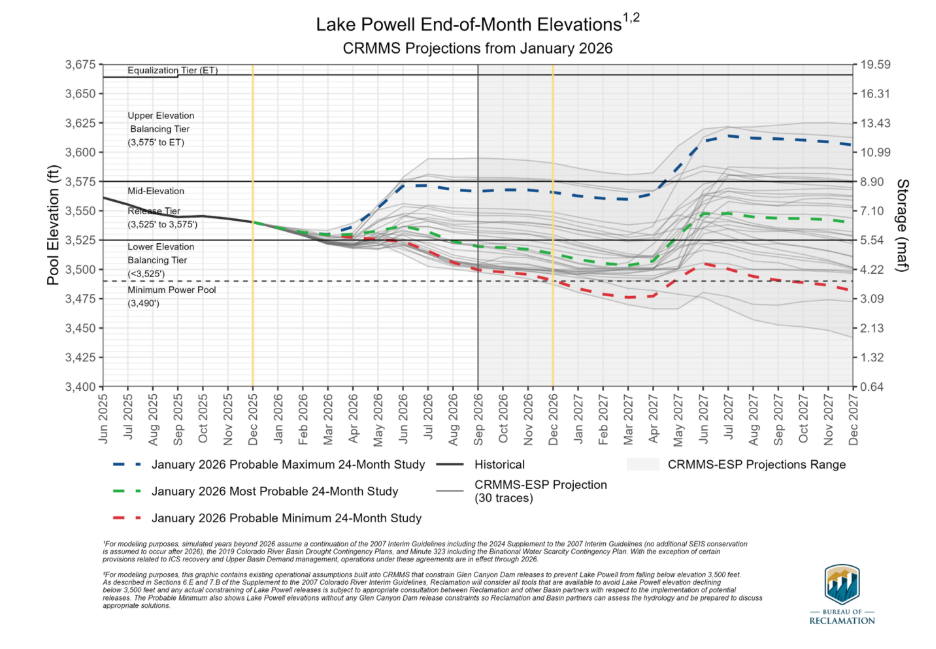

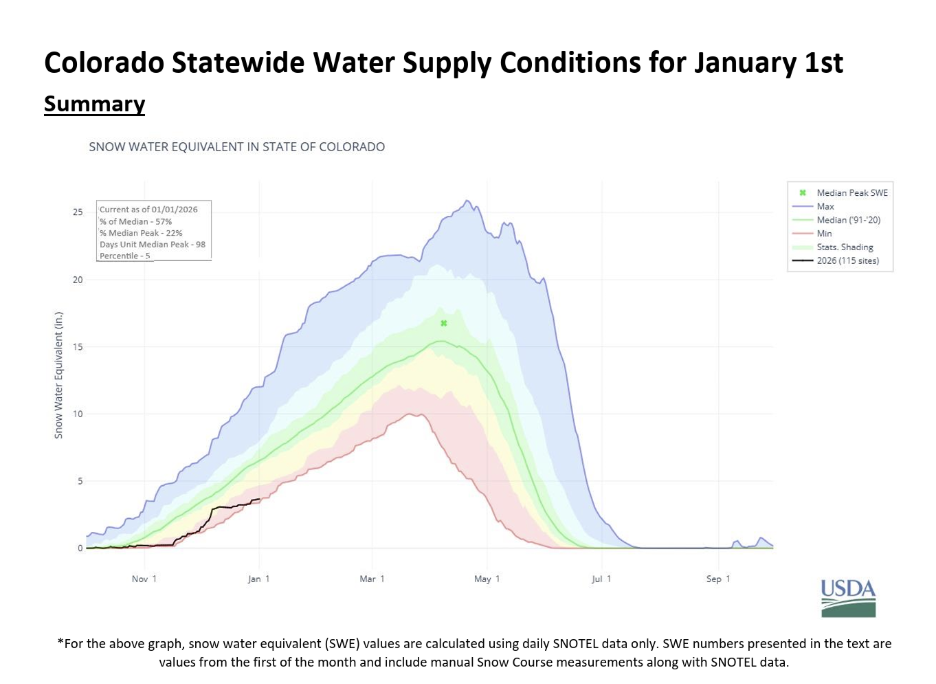

Meanwhile, the BOR 24-month projections released in October of 2025 suggested – and for many who have been tracking climate models for years confirmed – a worrying trajectory for water availability in the basin, with some models predicting Lake Powell dropping below the minimum level for hydropower as early as fall 2026.

The 24-month study, paired with the sobering, recently released NRCS report for Colorado Statewide Water Supply Conditions, underscore the imminence of future water management strategies that plan for profound shortages, and look to integrate flexible tools, policies, and programs that can respond to a severely diminished water supply and work proactively to minimize harm to communities, economies, and the critically, to the river itself.

What’s next?

Well, it’s a little hard to say. The states face a new deadline of February 14th to come to an agreement about the future management of the Colorado River. Unfortunately, following a recent meeting of governors and their representatives in Washington DC, agreement does not look likely. In mid-January, the Trump Administration issued a framework for five alternatives, which overwhelmingly propose cuts to the Lower Basin States, nearly all of which are likely to lead to litigation.

The long-anticipated draft environmental impact statement (DEIS) was issued on January 9, providing a preview of the menu of options for future management of the overstressed river. The DEIS outlines five potential frameworks for managing the river, and tests them against various climate forecasts. Some experts claim the models don’t go far enough to represent the likely extent and impact of prolonged drought in the Basin.

- No Action Alternative: assumes that after this year, reservoir operations would revert to pre-2007 conditions. Current drought-response adaptations would cease, and annual decisions would rely on outdated and broad authorities rather than strategies aimed at mitigating the risks the Basin faces now and going forward.

- Basic Coordination Alternative (Federal Authorities Alternative): The Draft EIS expressly recognizes that this alternative would not successfully sustain the basin for the term anticipated (20 years) but may work if needed for a short-term. Under most hydrologies, it may not sufficiently reduce the risk of reservoir drawdown in prolonged drought, potentially perpetuating low reservoir storage impacts on ecosystems and water supplies.

- Enhanced Coordination Alternative (Federal Authorities Hybrid Alternative): Intended to strike a balance between federal coordination and stakeholder-driven strategies that factor in Tribal water, it yields improved reservoir health (stability and predictability) under a broader range of hydrological conditions than the No Action and Basic Coordination Alternatives. The success of this alternative depends heavily on the size and extent of stakeholder participation and involvement.

- Maximum Operational Flexibility Alternative (Cooperative Conservation Alternative): Prioritizes system resilience and conservation, potentially achieving greater storage stability and flexibility if implemented effectively. It may require new agreements among stakeholders, voluntary contributions to conservation reserves, and broader water management tools. This alternative is likely the most protective of critical infrastructure and long-term ecosystem health because it integrates conservation reserves, proactive storage buffers, and measures that could support more stable instream flows and habitat conditions, benefiting native species and riparian environments. It’s important to note that in order to achieve the stability and reliability the Basin demands, this alternative assumes the largest cuts (of the proposed alternatives) to water user supplies and deliveries.

- Supply Driven Alternative: This alternative is designed to respond dynamically to actual water supply conditions, potentially triggering deeper conservation actions in dry conditions and moderating releases when supply is higher. This alternative has the potential to better align water use with hydrologic realities, reducing stress on storage and ecosystems during drought. However, the plan relies on operations that directly implicate competing interpretations of the Colorado River Compact and other elements of the Law of the River, which the Basin States have not yet been able to overcome. Like the others, this alternative depends heavily on broad agreements among states and stakeholders before implementation.

It’s important to recognize that all alternatives face a number of uncertainties, and no alternative fully eliminates the risk of low storage under extreme drought scenarios. This means monitoring, adaptive triggers, and stakeholder cooperation remain critical across all scenarios.

If the states don’t come together by the new Valentine’s Day (ironic, we know) deadline, it’s hard to know what will happen; however, a Federal alternative will likely result in litigation from the states. And, while there may be a time and place for litigation, the consequences of Colorado River management being tied up in court for the foreseeable future is bad news for a river facing dwindling supplies, a very grim snowpack, and increasing demand. It limits the flexibility and collaboration required for thoughtful, proactive response, and the kinds of solutions that the circumstances and the river demand.

Our own Sinjin Eberle said it best in his recent quote in this LA Times article:

“Ultimately, we would hope that all of the states and the federal government combined recognize that without the river being healthy and sustainable, industry is going to suffer, agriculture is going to suffer, communities are going to suffer. Hopefully the states can respond to that in a way that is comprehensive and allows for sustainability.”

Sinjin Eberle

More than two decades ago, Where Rivers Are Born helped establish the scientific case for protecting the small streams and wetlands that form the backbone of our river systems. This newly updated edition—developed by the University of Georgia’s River Basin Center in collaboration with leading freshwater scientists and American Rivers—reflects more than twenty years of additional peer-reviewed research on how headwaters function and why they matter.

The conclusion is even clearer today: rivers don’t begin where we boat, fish, or swim. They begin quietly—often invisibly—in small streams, wetlands, and seasonal channels that lace together our landscapes. These headwaters make up the vast majority of our stream networks and are essential to clean water, flood protection, biodiversity, and reliable water supplies downstream.

Drawing on hundreds of studies published since the original report, Where Rivers Are Born documents how small streams and wetlands slow floodwaters, recharge groundwater, trap sediment, and naturally cleanse pollution before it reaches downstream rivers, lakes, and drinking water sources.

The report shows that intermittent and ephemeral streams—many of which flow only seasonally—are especially effective at processing excess nutrients that otherwise fuel harmful algal blooms. It also explains that wetlands often labeled “isolated” are typically connected through groundwater and subsurface flows, playing a critical role in maintaining water quality and streamflow. Collectively, these headwaters support extraordinary biodiversity, store carbon, and sustain the ecological and economic benefits people depend on from downstream rivers.

That science stands in direct conflict with the EPA’s proposed Waters of the United States (WOTUS) rule. As we’ve written before, the rule relies on narrow legal interpretations that ignore how water actually moves across landscapes, excluding non-perennial streams and most wetlands from Clean Water Act protections. Where Rivers Are Born makes clear why this approach is so risky: removing protections from the very waters that filter pollution, moderate floods, and sustain river flows undermines the integrity of downstream waters the Clean Water Act is meant to protect.

Simply put, you cannot protect rivers by abandoning their sources—and any WOTUS rule that does so abandons both the science and the purpose of the Clean Water Act.

After more than 10 years of planning, the deconstruction of a human-made causeway that blocks an entire section of the lower Yakima River in Central Washington is underway.

American Rivers has long advocated for the causeway’s removal at Bateman Island. Freeing the river here will allow salmon and steelhead to migrate unimpeded for the first time in decades, maximizing significant habitat restoration investments in one of Washington’s largest watersheds and marking an important step towards healing the Yakima River Delta.

Salmon are essential to the culture and sustenance of the Confederated Tribes and Bands of the Yakama Nation, who are working tirelessly to replenish fisheries on the river, a major tributary of the Northwest’s great Columbia River.

We’re excited to see this major project begin and grateful for the collaboration between all our partners in the Yakima Basin Integrated Plan.

Learn more about the expected benefits to the river ecosystem below.

This story was originally published by the Washington State Department of Fish and Wildlife on January 5, 2026

Many years ago, people built a dead end where two rivers met — and blocked an ancient pathway for migrating salmon and steelhead.

Bateman Island is a beautiful place resting in the delta where the Yakima River flows into the Columbia River near Richland. While the exact history is unclear, around 1939 or 1940, a causeway (or raised path) was built in the river to reach the island, probably for agricultural use. Over time, the causeway and other modern infrastructure along the river have contributed to the development of a shallow pond of warm, stagnant water — perfect habitat for invasive fish to thrive and prey on young juvenile salmon and steelhead.

Blocking an entire section of the Yakima River, the causeway also fosters an overgrowth of vegetation that limits where salmon can swim. It also makes it difficult for juvenile salmon to migrate downstream to the ocean during spring and early summer, while also limiting passage for adult salmon returning to spawn in summer and fall.

Impacts to salmon

Today, while some populations of salmon and steelhead are on the rise in other parts of Washington — thanks to years of recovery work — the causeway has contributed to depressed populations in the Yakima River Basin.

In addition, the Yakima Basin has experienced drought for three years in a row, exacerbating impacts to salmon in this ecologically significant river delta. When salmon spend excessive time in warm, shallow water depleted of dissolved oxygen, it can be fatal. Swampy, stagnant water blocked by the causeway harbors a warm ecosystem of mosquitoes, algal blooms, overgrowth of a plant known as water stargrass, non-native predatory fish, bacteria, parasites, and degrades water quality. In summer 2024, high water temperatures in the Yakima River delta killed at least 75 sockeye salmon.

Warm water can also act as a thermal barrier, blocking fish passage and causing adult fish to stray or wait in cooler waters in the mainstem Columbia, decreasing their chances of successfully spawning.

Partners take action

This month, the Walla Walla District of the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers (USACE), Yakama Nation Fisheries, the Washington Department of Fish and Wildlife (WDFW), and the Mid-Columbia Fisheries Enhancement Group are working together to begin removal of the Bateman Island causeway. This work will improve fish passage, spawning habitat, water quality, and water movement. The collaborative effort began years ago with planning and public engagement. A feasibility study and environmental assessment were finalized in October 2024.

Project partners also led the removal of an upriver marina in August 2025, which eliminated an artificial habitat that was supporting a growing population of predatory, non-native fish. This resolved another problem for salmon in the river delta. The project included compensation to the marina owners through a fair market appraisal process and for the decommissioning of the facility.

On Nov. 7, the USACE, in partnership with WDFW, the Yakama Nation, the Washington State Department of Ecology, and the Mid-Columbia Fisheries Enhancement Group, awarded a $1.2 million contract to Pipkin Incorporated for the causeway removal. Excavation of the causeway is slated to begin as early as Jan. 5. The USACE has developed and will implement a water quality monitoring plan during and post-construction

“Mid-Columbia Fisheries Enhancement Group has been proud to work alongside regional partners for nearly 15 years — including early collaborators at the Yakima Basin Fish and Wildlife Recovery Board, Yakama Nation, and the Benton Conservation District — to elevate water quality and fish passage priorities in the lower Yakima River,” said Margaret Neuman, Executive Director of Mid-Columbia Fisheries Enhancement Group. “Restoring the Yakima River Delta is critical for the recovery of salmon, steelhead, and lamprey throughout the Yakima Basin. We are grateful to see the long-planned removal of the Bateman Island causeway move forward, restoring natural river processes, improving water quality, and supporting healthy fish migration throughout the system.”

Cultural significance of Bateman Island

Bateman Island and the Yakima and Columbia rivers are culturally important to the Yakama Nation and the Confederated Tribes of the Umatilla Indian Reservation. The broader community is also invested in this project, which was developed with extensive public input.

“This is a long-term collaborative effort, working together to get the process completed, working to get the permitting required, and working to also educate everybody, especially the local people near the island who are going to see changes in their area,” said Joe Blodgett, Yakama Klickitat Fisheries Project Manager and spokesperson for the Integrated Plan.

“The causeway and its resulting problems in the Yakima River are a high priority for Yakama Nation Fisheries’ staff,” Blodgett said. “The removal of the causeway is going to be a huge benefit for our first foods with the salmon returns and also to people living nearby who rely on clean, flowing water.”

Blodgett feels that “the removal of the causeway is a big win for many.”

“It is incredibly rewarding to see the years of collaboration come to fruition — the Yakama Nation taking the lead on fisheries, the Army Corps contracting out the excavation work, and WDFW co-managers supporting the coordination with Mid-Columbia Fisheries,” he said. It’s a great team with a lot of persistence to move through the long process to get here.”

The history of salmon in this area

Historically, the Yakima River was home to the second-largest salmon run in the Columbia River basin, behind only the Snake River. More than 800,000 salmon return to spawn and die here every year, enriching the river and the surrounding landscape.

Mike Livingston, WDFW’s south-central Washington regional director, states, “The Bateman Island causeway creates a bottleneck for salmon in the Yakima River delta and compromises our restoration work upriver, such as the major fish passage facility being built at Cle Elum Dam. The success of the causeway removal project will magnify benefits to the whole Yakima River system for salmon.”

Several salmon stocks have recently been reintroduced or supplemented into the Yakima River through collaboration between Yakama Nation and many other state and federal agencies. These include sockeye, coho, fall, spring, and summer Chinook, steelhead, and Pacific lamprey.

The causeway removal will benefit these species, as well as birds, other species nearby that live on land, and other aquatic species native to the area. Additionally, the project will improve water quality and enhance recreational fishing opportunities.

A more friendly future for fish

Restoring fish passage at Bateman Island will open the Yakima River delta to a better home and future for salmon and steelhead.

Project partners are optimistic about the health of the Yakima River delta as they look forward to continuing collaborations to nurture strong salmon runs and new recreation opportunities for locals and visitors to the area.

“As commander of the Walla Walla District, I am proud to be part of this effort to return the Yakima River delta to its natural state,” said Lt. Col. Kathryn Werback of USACE. “The island causeway blocks the river’s course, which has significantly impacted critical habitat for culturally significant fish for a long time. Removing it will begin reversing that harm through a restoration effort made possible by our strong partnerships with WDFW, the Yakama Nation, and Mid-Columbia Fisheries.”

Other partners

Additional stakeholders and tribal nations supporting the causeway removal include the Washington departments of Ecology and Natural Resources, the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, NOAA Fisheries Service, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, the cities of Richland and Kennewick, the Confederated Tribes of the Umatilla Reservation, Resources Legacy Fund, Roza and Kennewick Irrigation Districts, and outdoor enthusiasts. Trout Unlimited served a key role in the removal of the Columbia Park Marina, and the Benton Conservation District and the Yakima Basin Fish and Wildlife Recovery Board were early, critical partners in project identification and development.

The causeway removal is part of the Yakima Basin Integrated Plan, a coalition of local, state, and federal agencies, the Confederated Tribes and Bands of the Yakama Nation, and non-governmental environmental organizations that are collaborating on projects to benefit farms, fish, and communities in the Yakima River Basin.

The Integrated Plan, the USACE, the Department of Ecology, and the Washington Salmon Recovery Funding Board provided state and federal funding for the causeway removal. Yakama Nation also secured a grant from NOAA that funds fish passage improvements in the Yakima River delta.

See the causeway removal project in real time from the City of Richland’s time lapse footage.

Across the country and across the political spectrum, communities are demonstrating their desire for, and commitment to, clean water and healthy rivers. One example of this is how voters showed up to support rivers on election day. On November 6, voters overwhelmingly approved multiple ballot measures, buoyed by the American Rivers Action Fund, that support rivers, infrastructure, and parks.

In Texas, citizens passed Proposition 4 with 71% of the vote, authorizing a billion-dollar-a-year fund for water security and stream and floodplain restoration efforts across the state for the next 20 years. This is the largest state-based water ballot initiative in the history of the United States. Partners, including the National Wildlife Federation Action Fund and Texans for Opportunity, were vital to the effort, amplifying the issues with the Texas State Legislature, and to Governor Abbot and communities across the Lone Star State.

“Across the country, when water is on the ballot, water wins. Texans of all political stripes turned out to show they understand the need to fund water projects to sustain communities and wildlife,” says Karla Raettig, Executive Director of the National Wildlife Federation Action Fund.

In Idaho, Boise voters approved a 2-year, $11 million property tax levy that will supply critical funding for clean water, parks and urban trails, and wildfire prevention measures. Boise voters approved the measure with 81% of the vote, illustrating how integral improvements to Boise River habitat, walkable parks, and wildfire protection measures are to the quality of life across the city. The coalition effort was led by Conservation Voters of Idaho, which coordinated a substantial get-out-the-vote campaign, knocking on more than 10,000 doors across the city.

“Boise is great because of our open space, and the City has received a mandate that we must continue to expand and protect these special places and resources. We’re proud that Boise continues to show up big and united in shared values like protecting our river and open space,” says Alexis Pickering, Executive Director of Conservation Voters of Idaho.

Much of the water that we rely on comes from rivers, which also provide crucial habitat for fish and wildlife. Our economies, farms, and cities depend on river water for growth, and rivers offer unparalleled opportunities for reconnection with nature and with one another.

These wins at the ballot box build on other water funding measures that have passed with broad, bipartisan support, such as Propositions DD and JJ in Colorado, which have raised over $130 million for water conservation and river health projects across the state since 2020.

“Water security is a unifying issue across the political spectrum. No matter where you live or who you vote for, we all need clean water coming out of our kitchen taps, and we all want to be able to take our kids to the local creek to play,” says Heather Taylor-Miesle, Executive Director of the American Rivers Action Fund. “These wins will make life better in Texas and Idaho, and they provide a blueprint for actions other cities and states can take to protect their water wealth.”

When a major natural disaster strikes, local and state officials often turn to the federal government for assistance in preparing for extreme weather events and rely on it afterwards to help with the clean-up and recovery efforts.

Since 1979, the branch of the federal government responsible for this has been the Federal Emergency Management Agency, also known as FEMA. Originally formed under an executive order by President Jimmy Carter, FEMA is tasked with helping Americans before, during, and after a disaster.

Before an event

Before a disaster, FEMA helps communities and individuals prepare for an anticipated disaster with regular training, engagement, and education, so state and local officials are prepared to handle the event, evacuate people, and keep the community as safe as possible under difficult conditions.

This includes actions like knowing the flood risk in your neighborhood and, if your property sits in a FEMA flood zone, having flood insurance through the National Flood Insurance Program (NFIP), which is administered by FEMA. The agency also works with local and state planners to consider floodplain management to help reduce the risk of flooding to adjacent communities.

FEMA provides grants and other programs to help make communities more resilient to natural disasters, as well as offer training and educational tools to local and state emergency managers so everyone is prepared with the latest technology and best practices to respond to extreme weather events.

During the disaster

During a disaster, if the damage is significant enough to qualify for federal assistance, a governor or a tribal leader can apply for a Presidential disaster declaration. Once the sitting president approves a disaster declaration, FEMA coordinates with local and state leaders on providing the necessary assistance to support the recovery efforts.

In some instances, this may require FEMA to utilize the broader efforts of the federal government to support disaster response assistance, like requesting the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers to help with infrastructure assessments. In other cases, state authorities may have the appropriate help on the ground, but they need additional FEMA funds to ensure the work gets done, like overtime pay for local emergency responders and debris cleanup.

Clean-up and recovery

After a disaster, FEMA is still available to provide public and private assistance to recover and rebuild. FEMA will often work with local leaders on developing a recovery framework so communities can get the physical help and financial support as fast as possible to return to business as normal. This could be in the form of temporary housing while structures are rebuilt, or making sure communities are reconstructed with techniques that are designed to mitigate future disasters. FEMA also processes flood-insurance claims from homeowners with policies through the National Flood Insurance Program, or NFIP.

The role of FEMA has evolved since it was first established in 1979. It continues to change as more responsibility has been placed on it, due to an increasing number of natural disasters that have caused significant economic damage in communities across the United States. There is a current push for states to take more accountability for disaster response, with FEMA playing a smaller role and pushing states to play a bigger role in paying for the disaster preparation, response, and recovery. At the moment, state capability to step up and lead in disaster management varies widely, so it is essential that FEMA remains well funded and rebuilds its staff to help all communities prepare for, respond to, and recover from floods and other disasters.

It feels like every year, meteorologists are reporting more and more “100-year floods.” This term is often misunderstood and misrepresented from a scientific perspective.

Meteorologists, floodplain managers, and the media often use the term “100-year flood” as shorthand for an event that has a 1 percent chance of occurring in any given year. It does not mean that the event will occur once every 100 years. Let me explain.

This type of statistical analysis is done by hydrologists — scientists who study the occurrence, distribution, and movement of water. They can predict how frequently a major precipitation event is likely to occur in a specific area.

Hydrologists need at least 10 years of data to perform a frequency analysis in locations to predict how often a major precipitation event can cause significant flooding. The more historical data available over a longer period, the more accurate the prediction.

Let’s look at a hypothetical river — the Pretend River — for which a hydrologist gathers historical rainfall patterns and stream data and finds that there is a 1 percent chance of a flood cresting 20 feet above its normal level each year at river mile 4.5. A flood of that size, at that location on the Pretend River, is determined to be the “100-year flood” for that river. Our hydrologist also determines that a flood cresting at 23 feet has a 0.5 percent chance of occurring each year, so that size flood is determined to be a “200-year flood,” while a flood cresting at 25 feet has a 0.2 percent chance of occurring each year and is determined to be a “500-year flood,” and so on.

Just because a 100-year flood occurs doesn’t mean it won’t happen again for another 100 years. The risk of these different-sized events reoccurring remains the same every year, statistically.

The reason why more “100-year floods” seem to be occurring is that many areas are seeing larger floods more frequently. Let’s say our hydrologist redoes her flood study ten years later and she now finds that there’s actually a 1 percent chance of a flood cresting at 25 feet every year. What was once a “500-year flood” is now a “100-year flood.”

Why is this shift happening? One of the main reasons is global warming, which causes major precipitation events to occur more frequently because global warming causes the atmosphere to hold more moisture, which translates into more extreme rainstorms repeatedly producing record-breaking events. This is increasing the likelihood that a 100-year flood event can happen two years in a row.

Take Houston, Texas, where the city experienced 500-year floods three years in a row. The first was produced on the Memorial Day holiday in 2015 and 2016, then again by Hurricane Harvey in 2017.

Researchers from Princeton University published a paper in 2019 that determined 100-year floods could become annual occurrences in New England by the late 21st century due to increased storm surge, coastal sea level rise, and more frequent tropical storms.

So the question before us is not will a 100-year storms occur, the question is how can we mitigate the impacts to people, property, and our communities? Learn how protecting and restoring floodplains can help communities adapt to increasing flood risk.

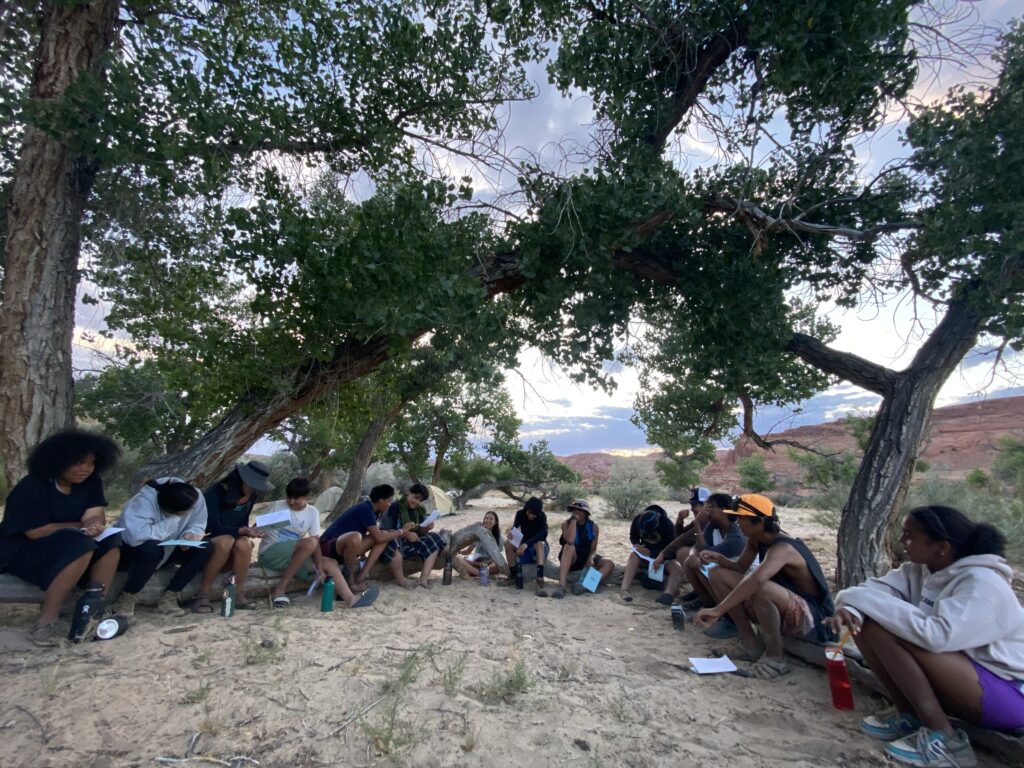

The canyon was a sanctuary of morning shade as we spread out across the natural sandstone benches. The rocks around us mirror the color of our own skin—an intergenerational group of youth and elders nestled in for reverence. The silence before our prayer began was accompanied only by the steady trickle of the creek, a melody to the distant waterfall. The gourds rattled to a familiar beat, and our voices followed the tempo. Eyes closed, smelling the scent of burning tobacco. The harmony of voices, singing in unison, the appreciation for water, for the river.

Months passed after that morning, and I sat in a forest of ponderosa on the rim of that same sacred canyon. I sit pondering how the stream-carved chasm sounds today. It’s absent our singing voices, although our blessings remain in the spirit of that place. Drifting away from the daydream, I’m filled with contentment knowing that the medicine created, shared, and received lives on with the Native youth who sang with me that day.

I live, work, and play across the Colorado Plateau, committing most of my time to engaging with Native youth in outdoor spaces. I build community with Native youth on traditional farms across the Navajo Nation, in deep canyons and forests, and on all the mesas in between. Indigenous youth are our future—a proclamation that became abundantly clear this year as I facilitated culturally relevant outdoor education programs with various nonprofits in the Four Corners region. This level of community engagement in relation to the land represents movement toward the protection of biocultural diversity. Through generations of caretaking, the land of Indigenous peoples has maintained immeasurable biodiversity. The degree of protection and caretaking is evolving in challenge and intensity due to the unfortunate reality that Native communities are disproportionately affected by the severe impacts of climate change. The consequences of climate catastrophe will be left in the hands of Indigenous youth. So how do we inspire them to play a part in the story they are woven into?

It begins with reminding youth that they hold an intrinsic connection to the land. One of the many lasting tactics of colonialism is the forced disconnection of Native peoples from the land. Decades of violent removal, boarding school, and dispossession of land and water have left generations of youth to feel they don’t belong to the land the way their ancestors did. This lack of belonging is exacerbated by the gatekeeping of outdoor spaces by white communities. Socially discouraged accessibility to the outdoors is a barrier to maintaining cultural connection to place.

Growing up in the storied land of the Northern Arizona desert, I began shaping my personal relationship to land at a very young age. My time in red sand and between canyon walls was enriched by the teachings of my family, of my Diné community, that we are a part of this land. While I was never involved in an outdoor youth program, my proclivity for facilitating such programs stems from my belief that Indigenous youth should have limitless opportunity to design an intentional relationship to land and water based on their cultural and personal values.

This year, I had the privilege of helping to facilitate the annual RIISE (Regional Intertribal Intergenerational Stewardship Expedition) trip through the Grand Canyon Trust. Indigenous youth and elders gathered to share prayer, tradition, and abundant laughter along the Colorado River. On this trip, we honored the fact that spirit, knowledge, and tradition live in a physical space, brought to life by the stories told and prayers sung. To pass on teachings, Native youth must have access to these places. I’ve shared space and time with over a hundred Indigenous youth this year, and a resounding theme among all of them is a deep desire to know their culture by personally experiencing the land their relatives knew so intimately.

The relationship they desire has been taken away from them by the settler-colonial state we live in, which exploits racial identities to gain economic capital. National Parks are an example of this racial exploitation: land dispossessed from Native peoples has been turned into a commercialized and profitable space. Outdoor recreation is a predominantly white space, a privilege to those who can afford and feel safe in such environments. Outdoor recreation spaces are curated for the white experience, therefore becoming inherently exclusive. Native youth rarely see people of their own cultural background or race represented in the outdoor industry, thus perpetuating the false narrative that they don’t belong.

Providing a safe learning space for Black and Brown youth outdoors is a revolutionary act that uplifts both the individual and the community. Time on the land, in community, ignites a sense of belonging; an opportunity to heal the youths’ relationship with land. I observe this phenomenon when facilitating Native Teen Guide in Training trips through the Canyonlands Field Institute on the San Juan River each summer.

We walk alongside sandstone walls that tell of migration in the river corridor from millennia ago. The tradition continues as the youth paddle down the river. This river trip is the first and potentially only time many of these youth will have access to experiential learning and cross-cultural exchange in an outdoor recreation space. The riotous laughter of the youth ricochets across the water as we spend days passing by boats of people who don’t look like us. Some youth notice; others are blissfully oblivious to the racial disparity on display on their ancestral river. Despite these observations, we find our belonging in the stories of our people that etch themselves into the rocks, plants, and animals. Our night air is filled with a steady drum as we round dance, our hands interlaced, feet shuffling in red sand, an offering to the stars.

Outdoor programs geared toward Native youth have an impact that shouldn’t be limited to a singular experience. The magnitude of a culturally-relevant trip is, in essence, a reclamation of a relationship to land and water. How do we ensure the continuous growth of this relationship? We continue to provide Native youth with the opportunity to learn and build relationships with the land and water—to know the river and land as beings with a spirit, as relatives. We help them cultivate an inclination to care for such relatives. By instilling the traditional belief that our lineage is rooted in the land and the water, we can help create a generation of protectors. People protect what they know; they protect who they care about.

Encouraging the changemakers of the future does not eliminate the feeling of helplessness regarding the water and climate crisis in the Southwest and around the world. On a sunbaked afternoon, bellies full and lungs worked from hours of games at Redwall cavern—in Marble Canyon on the RIISE trip this past summer—the Native youth settled in for a floating talk. They sank into their seats on the rafts, all tied together for the moment, allowing the serenity of the walls to add a dramatic effect for our discussion of water in the West.

Complex topics like water law, legislation, and litigation—and related and problematic jargon, too—hindered a complete understanding of Western water among the youth. A discussion like this can have a similar effect on adults. Worried that we were losing their attention, my mind raced with ideas on how we, as facilitators of the discussion, might connect this topic to their lives, personally. Thinking on my feet, I reminded them of culture: of the days we had already spent giving offerings and blessings to the land and water, learning and strengthening our bond to the sacred. This is specialized knowledge, I told them truthfully.

“There are people in windowless rooms making decisions about a river they may have never floated on, bathed in, or prayed to. Despite this, you cannot forget the generations of wisdom passed through this place, through you, that instructs accountability as land and water protectors.” This dynamic connection to ancestral homelands is what sets Native youth apart; it is their superpower against a world committed to poisoning the earth.

Indigenous youth play a critical role in the unfolding story of our planet. They, too, hold wisdom. The significance of intergenerational knowledge exchange becomes especially evident when in the presence of Native youth. One teaching I received from their enlightened youthfulness is the seamless transition between prayer and play. After an hour-long ceremony at each stop in the Grand Canyon, play promptly ensued. It is a teaching applicable to anyone living in this time, an honoring of the dualities omnipresent in the Indigenous experience. The youth raised my belief that there is room for reverence and laughter in sacred spaces. Our presence throughout the Canyon was marked by steadfast joy: joy for the chance to be in community, to reinhabit the spaces of our ancestors. In this way, joy was our act of resistance.

It’s midday at Whitmore Panel in Grand Canyon (If you know this place, you know scorching heat). We gathered around three young Zuni wisdom holders. We stood, backs of legs burning, listening to the youth sing us into the place in a good way. Taking in the stories on the wall, one of the Zuni youth recognized a symbol. The same symbol he paints on his traditional pottery. Thousands of years between him and his ancestors disappeared at that moment, a lineage connection so profound it forced all of us to recognize the depth of our presence. The presence of Native youth on sacred land is essential for the continuation of culture and the envisioning of the future.

Resistance to the exclusionary character of outdoor recreation is reconnecting Native youth to their right to access their ancestral homelands. Inclusivity begins with acknowledging the barriers to access and understanding how these barriers are a result of systemic oppression. Following this acknowledgment comes owning the part we each play in upholding these systems. Ultimately, this privilege can be leveraged to support Native youth outdoor programs. These programs are gaining traction as we collectively work toward Indigenizing the future. This future honors Indigenous lifeways and values like reciprocity, care, and relationship building. You can be a part of the movement by supporting organizations like these:

- Rising Leaders—Grand Canyon Trust

- Native Teen Guide In Training—Canyonland Field Institute

- Paddle Tribal Waters—Rios to Rivers

- River Newe

- Pandion Institute

- Pollen Circles

You can amplify your support by advocating, donating, and building relationships with your local Native youth programs and community.

Guest contributor Chyenne (she/they) is a Diné adzaani from the small desert town of Page, AZ. The sandstone mesas, canyons, and sagebrush-painted plateaus became her teachers, instilling her creative capacities. Today, Chyenne works and writes as a dedicated land and water protector, applying her lessons from her homeland alongside a MA in Indigenous Studies and BA in Social Justice and Environmental Studies from Prescott College in her work with various non-profits in the Four Corners region.

On the evening of November 19, a packed conference room in the Denver West Marriott erupted in cheers when the Colorado Water Conservation Board approved one of the largest ever dedications of water for the environment in Colorado’s history. This new deal, if completed, will ensure that water currently running through the aging Shoshone Hydropower Plant on the Colorado River, deep in the heart of Glenwood Canyon, will keep flowing through the canyon when the plant eventually goes off-line. It’s not a sure thing yet – water court wrangling over the details and financial hurdles remain. But the Board’s action was a crucial step forward.

Currently, when the plant is running full steam, 1,400 cubic feet/ second (think 1,400 basketballs full of water passing by every second) is diverted out of the river into a tunnel and then into massive pipes visible against the canyon walls, where the power of falling water spins turbines to generate electricity. The water is then returned back to the river. Under the new deal, when the plant stops operating (it is over 100 years old and vulnerable to rockfall), the water would instead stay in the river, vastly improving conditions for fish and the bugs they eat in the 2.4-mile reach between the diversion and the powerplant’s return flows. The dedication of the plant’s water rights to that stretch of river would bring benefits that ripple hundreds of miles up and downstream because of the crucial role these water rights play in controlling the river’s flow through Western Colorado.

In Colorado, as in most of the West, older water rights take priority over newer ones when there’s not enough water to satisfy everyone’s claims. On the Colorado River, the Shoshone Hydropower rights limit the amount of water that can be taken out of the river upstream by junior rights that divert water from the river’s headwaters through tunnels under the Continental Divide to cities and farms on the eastern side of the Rocky Mountains. The new deal to enable the Shoshone rights to be used for environmental flows would preserve those limitations on transmountain diversions in perpetuity.

Upstream from the power plant, near the ranching town of Kremmling, Colorado, the river carries less than half the water it would without the existing transmountain diversions. This stresses fish populations and the iconic cottonwood groves that line the river. The Shoshone rights downstream prevent these diversions from being even larger. Because the power plant returns all the water it uses to the river without consuming it, the water continues to provide benefits downstream from the plant to rafters, farms, cities and four species of endangered fish that exist only in the Colorado River Basin. Securing these flows for the future is particularly important as climate change continues to reduce the river’s flow, which has already declined by roughly 20% over the past two decades.

The people cheering in the hearing room represented cities, towns, counties and irrigation districts from up and down the Colorado River. Their entities had pledged ratepayer and taxpayer dollars to help secure the rights in the complex transaction spearheaded by the Colorado River Water Conservation District. Environmental organizations, including American Rivers, Audubon, Trout Unlimited and Western Resource Advocates, were also parties to the hearing and supportive of the deal, but were vastly outnumbered.

The Coloradans cheering in that room were there because their constituents’ livelihoods, clean drinking water and quality of life depend on a living Colorado River. American Rivers is proud to stand with them and will continue advocating for the completion of this historic water transaction.

When the city of Stockton, California, closed the Van Buskirk Municipal Golf Course in 2019, local leaders were presented with a prime opportunity. The community of South Stockton, an underserved neighborhood, needed more green space and outdoor recreational opportunities. It also faced the looming threat of catastrophic flooding due to climate change and the aging flood infrastructure along the San Joaquin River. Now, with 192 green acres available, the city could potentially solve both problems if it worked toward a creative, nature-based solution.

A historic floodplain

When the Yachicumne Yokuts and Miwok Tribes were the primary stewards of this portion of California’s Central Valley, the area had been freshwater wetlands that were naturally designed to flood. When settlers arrived in the mid-1800s, the wetlands were rapidly replaced with agricultural fields, and the river was hemmed in by levees built to protect farms and crops from flooding. Over time, Stockton grew into an urban and diverse community of more than 320,000 people.

Although they remain the main tool to contain floodwaters, levees in the Central Valley are aging and in need of repairs. If the network of levees remains in its current state, it poses a great flood risk because the levees stand to fail as extreme precipitation threatens the region.

This is an equity issue. The primarily working-class communities of color living near the levees lack the financial resources, like flood insurance, to recover from the hazards of living in a historic floodplain.

As climate change increases extreme precipitation events and flooding, 1-in-5 San Joaquin River Delta residents will experience flooding each year, costing the city more than $28 billion in damages and impacting more than 17,000 homes by 2050, according to a study by the state of California. Finding a solution to address this risk is critical.

Solution: Build a park and return floodplains to their natural state

The historic wetlands native to the Central Valley were nature’s solution to flooding as the flat lands naturally disbursed excess water whenever the San Joaquin River was inundated.

Levees that set the river in place didn’t allow it to breathe and flood like it naturally would. American Rivers is working with the city of Stockton, the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, and community partners to address the aging levees and subsequent flood risk. Through the Van Buskirk Park Revitalization project, the city is working to provide recreational areas, while the Army Corps is leading the effort to enhance the levee system along the San Joaquin River.

These projects have the unique opportunity to reconnect the river to historic wetlands and reduce flood risk, while providing more access to green recreational spaces, and potentially restore the area to a biodiverse habitat for wildlife.

The difficult part is the planning. The city has been working since 2021 to plan the park revitalization efforts while coordinating with the Army Corps, community partners, and project partners to plan the levee project at Van Buskirk Park. Meanwhile, the Army Corps is also working to create room for low-impact recreation into the potential setback levee area, as required by the city, as well as the Van Buskirk family, when the land was given to the city.

What to do with the levees?

A big question is whether the Army Corps will repair and enhance the full levee where it currently stands or move a portion of the levee at Van Buskirk Park back from the river to create mitigation space that can give the river room to flood.

Setting back levees produces an environment for fish, birds, and endangered species, while reducing flood risk to the community.

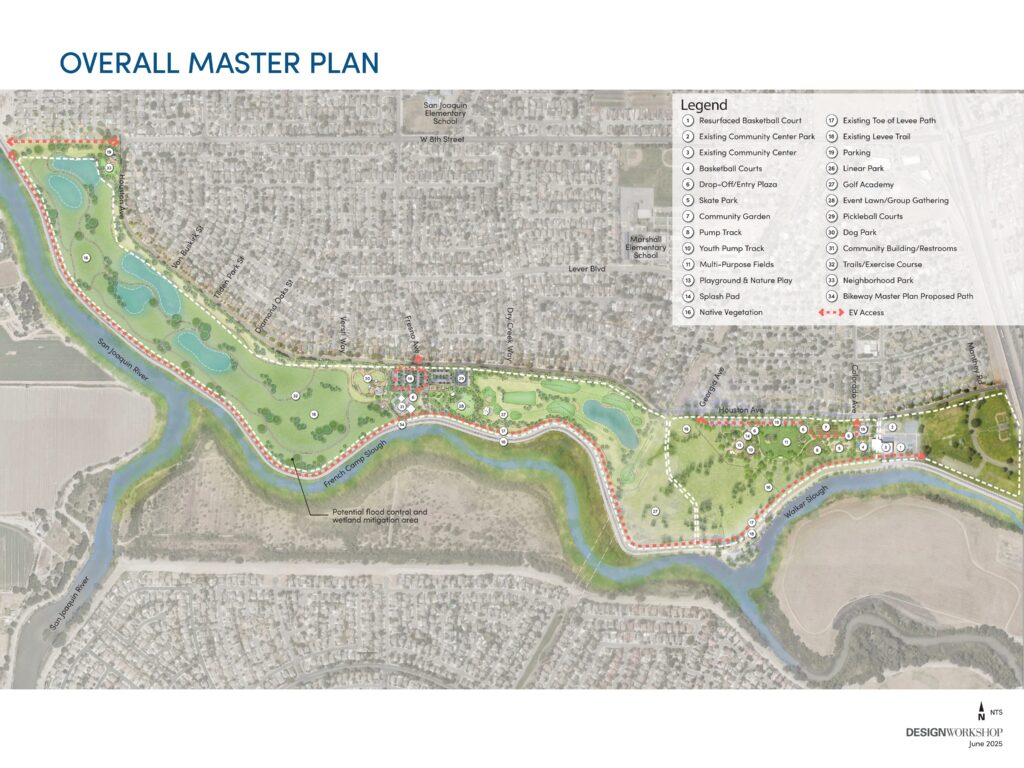

The city of Stockton approved a master plan for the park revitalization project in 2023, which is when American Rivers joined to facilitate communication between different stakeholders and partake in planning the levee project. Since then, progress has been made to fund and permit the first phase of the park revitalization. The Army Corps is planning to enhance some stretches of the levee along Van Buskirk Park, but it won’t make a final determination on setting back a portion of the levee until 2029.

Until then, construction for phase one of the city’s revitalization efforts is expected to begin in 2026, and that will include improving and building public amenities, including a community garden, bicycle pump track, splash pad, and other recreational spaces. The public should begin to see the immediate benefits of having more access to outdoor spaces. Although the decision to set back a portion of the levee is still in the air, there is incredible potential for an ecologically diverse, natural floodplain that will better protect the city from catastrophic floods.

A model for flood-prone communities

Both the Lower San Joaquin River Project and the Van Buskirk Revitalization Project complement each other to provide a model for other communities looking for green spaces and flood protection. For the revitalization effort, the city of Stockton completed several community meetings and surveys that led to the Van Buskirk Master Plan and the upcoming construction of Phase 1. As the project and funding progress, the city plans to hold even more meetings to ensure that the master plan holds true to the needs of the community. Upon completion, not only will people have renewed access to the park, but their involvement in park planning will also boost further engagement. Meanwhile, the US Army Corps of Engineers has the potential to create a setback levee that provides space for the San Joaquin River’s natural processes, while strengthening flood protection. These are exactly the kinds of innovative approaches we need if we want to work with our rivers rather than against them.

More information about the Van Buskirk Park Revitalization project can be found here.

Thank you to all project partners, including the City of Stockton, US Army Corps of Engineers, San Joaquin Flood Area Control Agency, Department of Water Resources, Restore the Delta, and Trust for Public Land.

The unassuming wetland is easily overlooked. After all, they often aren’t majestic like mountain lakes or fun-filled like beloved city riverwalks. But these understated terrains are hidden powerhouses that purify clean water, protect communities from flood damage, and provide habitat for a wide array of species. Among those, the hunter’s, the birder’s, and animal lovers’ delight: waterfowl.

Many of these wetlands form within floodplains, low-lying lands along rivers that naturally flood. The transformation comes quickly after a storm. What was once a dry or muddy landscape quickly comes alive as flood water flows over the land, tempting mallards, pintails, and waterfowl of all kinds to flock to these vital habitats to feast on nutrient-rich seeds and small aquatic creatures, rebuilding the fat reserves that fuel their long migrations. The shallow water creates easy feeding grounds and sheltered havens to rest between flights. Waterfowl, like so many other floodplain-dependent species, have evolved their life cycles to the natural flood pattern.

Unfortunately, more than ninety percent of floodplains in the lower 48 have been disconnected or degraded, contributing to more than half of wetlands being lost, and they continue to disappear at an alarming rate. Each acre drained means fewer places for birds to land and fewer natural floodplains to buffer nearby communities from floods.

One of the main governmental agencies that can make or break the health of our nation’s floodplain wetlands — and the services they provide for humans and waterfowl — is the Federal Emergency Management Agency. This agency’s choices on paper can shape what survives after the next storm, from homes kept out of harm’s way to wetlands where life thrives.

3 FEMA programs that impact floodplains, wetlands, and waterfowl

1. National Flood Insurance Program

NFIP offers flood insurance to reduce the financial risk to flood-prone homeowners. It covers flood events typically not covered by homeowner’s insurance. For homeowners to be eligible for the NFIP, a community must put in place minimum standards that guide where and how floodplains are developed. The program relies on FEMA flood maps that show where flooding is most likely and to shape how and where we build.

When construction occurs in floodplain wetlands, the wetlands are commonly drained and filled to make way for homes and roads. Local communities then lose the natural flood protection healthy wetlands offer, and waterfowl lose their habitat. Communities that go above and beyond the minimum standards to keep floodplains open for nature to do its job, storing floodwater and providing space for wildlife, can enroll in the Community Rating System (CRS).

CRS rewards communities with lower flood insurance rates when they take extra steps to build away from high-risk areas and conserve wetlands within floodplains, creating a long-term incentive to protect these irreplaceable landscapes. This allows protected floodplains to become seasonal havens where shallow waters brim with ducks and geese. Beyond prevention, FEMA also works to restore floodplains that have already been lost.

2. Hazard Mitigation Grant Program

The Hazard Mitigation Grant Program helps communities recover from floods and reduce future flood risk through projects like home buyouts and floodplain restoration. Funding becomes available to states, local communities, and tribal governments after the president declares a disaster. When implementing voluntary buyouts, local communities use FEMA funding to purchase flood-prone properties and remove the high-liability buildings. This begins the process of potentially allowing floodplains to recover and come back to life. But the decisions that communities make next are important.

Once FEMA buys out the properties, the agency encourages the land to be managed for natural floodplain and wetland restoration, but does not carry out the restoration work itself. Instead, local governments and community partners decide how each lot is cared for. When the land is left as mowed grass, its ecological value fades. When the land is restored with native plants and reshaped to hold water, it becomes a flourishing wetland again, reviving migratory bird habitat.

3. Pre-Disaster Mitigation Program

FEMA doesn’t just help communities improve their flood resilience after a flood; the Pre-Disaster Mitigation Program can take on acquisitions and other flood mitigation projects before the flood happens. In recent years, PDM got a huge boost with the creation of the Building Resilient Infrastructure and Communities program, which has unfortunately been rolled back under the current Administration.

Through BRIC, FEMA started funding more natural flood-management strategies called nature-based solutions, including programs that reconnect and revitalize floodplains, which create the shallow pools and marsh vegetation that migrating waterfowl rely on each spring and fall.

Advocating for FEMA policies that work with nature by giving rivers room to flood without inundating property and by allowing storm drainage to settle helps support our feathered friends. As storms grow stronger, FEMA can help implement common-sense limits on risky development to avoid draining and destroying our valuable wetlands.

In the stillness of a morning wetland, you can see what’s at stake: a living landscape that protects us as surely as we protect it. Across the country, wetlands are vanishing every year. Now is the time to protect what’s left.

Mountain meadows make up a small percentage of the land area in the Sierra Nevada, but not as small a percentage as once thought. This is exciting news as they have an outsized impact, often functioning as high-elevation floodplains. As snow melts in the springtime, meadows act like a sponge for cold water, holding on to it until the drier months of the year when downstream communities need water most. They also act as a biodiversity hotspot for birds, fish, amphibians, wetland plants, and insects. And a new model is revealing that there may be more meadows in the Sierra than previously estimated.

Scientists from the U.S. Forest Service have developed a system to identify potential “lost meadows.” The lost meadow model is based on the idea that disturbances like overgrazing, logging, and mining can disrupt the stability of a meadow, leading to big changes in their physical structure and biologic communities. One of the most troubling changes is the encroachment of large trees onto the former meadow surface. These trees use up water that was formerly available for wetland plants, and they increase fuels in forests that are already at high risk of catastrophic wildfire.

Degradation like what is pictured above can render historic wetlands unrecognizable to a typical observer, but the lost meadow model uses satellite and hydrological data to narrow down the search. With these tools, thousands of acres of potential lost meadows were identified across the Sierra Nevada.

This summer, American Rivers began a multi-year effort alongside the South Yuba River Citizen’s League and the U.S. Forest Service to find out how many of these lost meadows there really are in the North Yuba watershed in northern California, whose headwaters are almost entirely contained within the Tahoe National Forest. Field technicians like me spent months bushwacking through the Tahoe National Forest searching for these potential meadow sites by monitoring their vegetation, hydrology, and geology to determine if they were indeed historic wetlands and if they could be restored.

One season in, the results are surprising: after assessing more than 1500 acres of potential lost meadow sites, a vast majority were accurately predicted by the model (many were even bigger than projected!). We won’t have all the numbers until the project is complete, but the implications of our results so far are significant. If there are even half as many lost meadows in the Sierra Nevada as the model predicts, the restoration of these wetlands could substantially increase the water storage capacity of the Sierra Nevada, bring back historic habitat for wetland species, and sequester more carbon than is currently possible in their degraded state.

The benefits offered by the restoration of lost meadows in this region don’t stop there, though. As catastrophic wildfire risk continues to grow nationwide, it is clearer than ever that responsible forest and watershed management is crucial to protecting rivers, wildlife, and people. Strategic lost meadow restoration could lead to significant forest fuel reduction in a region that desperately needs it. Meadow restorations that remove unhealthy growth, create natural fire breaks, and increase surface water during the driest seasons become ever more important, and understanding lost meadows could be key to accelerating fire-safe restoration across the Sierra Nevada and beyond.

These findings open an exciting new chapter in meadow restoration. At the conclusion of this watershed-scale assessment, we’ll be able to begin exploring entirely new restoration techniques at meadow sites we didn’t know existed, working in collaboration to unlock all the benefits these ecosystems can provide.