White River

Fatal Attraction

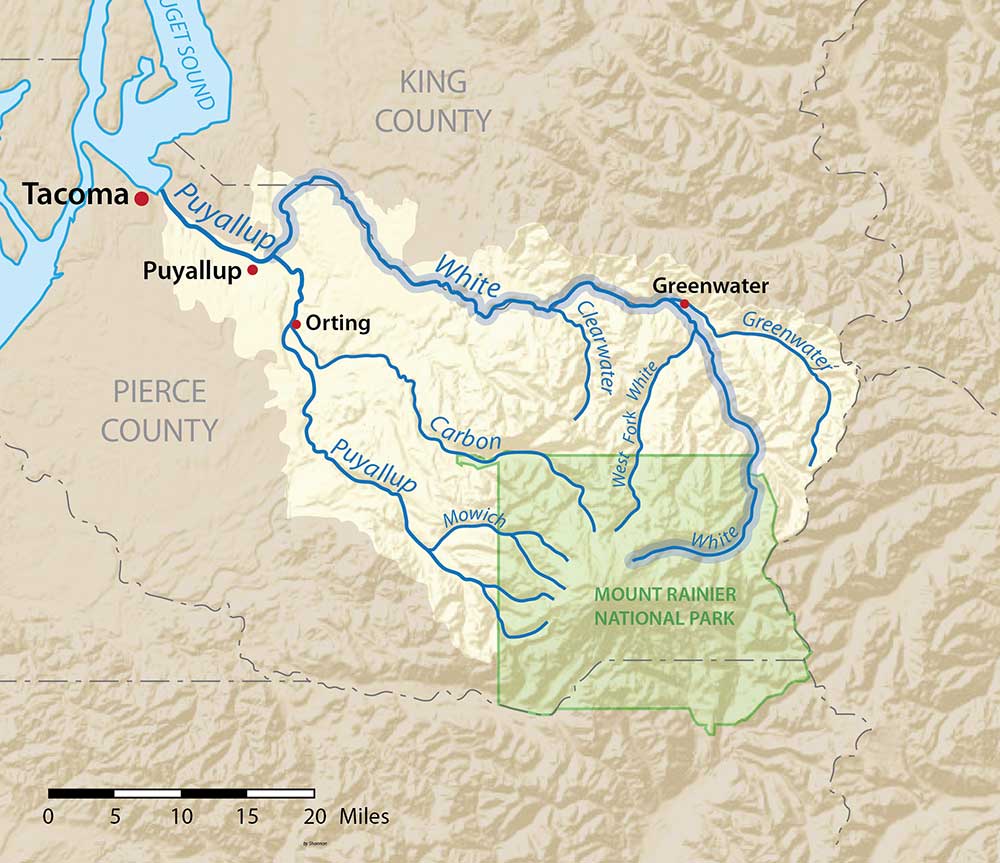

From Commencement Bay in Puget Sound, follow the Puyallup River upstream like the hundreds of thousands of pink salmon that migrate in the same waters as endangered chinook, steelhead, and bull trout. Veer left at the White River confluence and soon you will run headlong into the Buckley Diversion Dam, an antiquated 15-foot barrier that blocks spawning migrations to the pristine watershed below 14,410-foot Mt. Rainer.

If you were a fish, this is where you would likely die. That’s how it happens for as many as 200,000 salmon a year that fall victim to the hazardous fish trap that has not been upgraded since it was built in 1941. The fish trap at Buckley is supposed to catch the migrating salmon so they can be placed in trucks and transported around the larger Mud Mountain Dam a few miles upstream. But the trap is too small, no longer sufficient for the large numbers of salmon overwhelming the obsolete system.

It’s an ugly blemish on an otherwise beautiful river. Originating from the Winthrop, Emmons, and Fryingpan glaciers in Mt. Rainier National Park, the White River is one of six river systems flowing from the most glaciated peak of the contiguous U.S. From the flanks of the iconic volcano, the river travels 68 miles and drains 494 square miles before flowing into the Puyallup River east of Tacoma.

Along the way, the White River is enjoyed by kayakers, anglers, hikers, and visitors to the national park and the surrounding area. It is home to four species of salmon (chinook, coho, chum, and pink), as well as steelhead and bull trout. The river’s salmon and steelhead are central to the culture of the Muckleshoot and Puyallup Indian tribes.

Did You know?

Chinook salmon, summer chum and bull trout in the Puget Sound were listed as threatened under the Endangered Species Act in 1999. The listing was catalyst to the Puget Sound Salmon Recovery Project.

According to the Washington State Recreation and Conservation Office the recovery plan has an estimated cost of 1.42 billion dollars for the first ten years.

The sharp decline in salmon has led to the decline of killer whales in the region, which rely heavily on salmon as a food source.

WHAT STATES DOES THE RIVER CROSS?

Washington

The Backstory

Mud Mountain Dam was built by the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers for flood control in the 1940s. The dam blocks anadromous fish passage, so a “trap and haul” system was instituted, in which fish are transported around the dam by truck. Buckley Diversion Dam supposed to serve as the trap. However, the poor condition of the dam and its fish collection facilities cause thousands of salmon and steelhead to die each year, especially during pink salmon runs. Those that do make it into the overcrowded fish trap are often exhausted, impaled on rebar, or injured from the cramped holding facilities, which reduces their chances of spawning after release.

Let's stay in touch!

We’re hard at work in the Pacific Northwest for rivers and clean water. Sign up to get the most important news affecting your water and rivers delivered right to your inbox.

The failing system undermines more than $150 million in taxpayer funds spent each year to restore salmon to rivers and streams around the Puget Sound, including the threatened chinook. Ironically, Buckley’s alleged purpose since it quit diverting water to a hydropower project more than a decade ago is solely to assist the recovery. Instead, routine repairs to Buckley Dam require sharply reduced water releases from the upstream Mud Mountain Dam, drying up 29 miles of river and stranding juvenile fish migrating to Puget Sound.

Worst of all, hundreds of thousands of adult salmon are left to die below Buckley Dam before they can spawn. The ongoing saga placed the White River near the top of our American’s Most Endangered Rivers® list in 2014.

The Future

Since 2007, NOAA Fisheries has told the Corps of Engineers that it must upgrade the fish trap at Buckley Diversion Dam in order to meet its legal obligation to protect threatened Puget Sound chinook and steelhead under the Endangered Species Act. According to NOAA Fisheries, the White River has a wild spring chinook run that must be restored if the larger population of Puget Sound chinook salmon is to recover. Still the Corps has failed to take any action.

American Rivers and its partners have called on the Army Corps to design and install a modern diversion structure and updated fish trap by 2017—the soonest feasible time for completion of such a project while avoiding another massive fish kill during the 2017 pink salmon run (Puget Sound pinks run in odd-numbered years).

Replacing the dam and fish trap is a relatively modest investment (approximately $60 million) in light of the billions spent to date to protect and restore Puget Sound salmon. Modern fish trap facilities exist on nearby rivers like the Baker and Cedar, and there is no reason for the White River, and its rare spring chinook population, to lag behind. The Corps has an obligation to provide safe, timely, and effective fish passage with a complete fix to the dam and fish trap.