SAN SABA

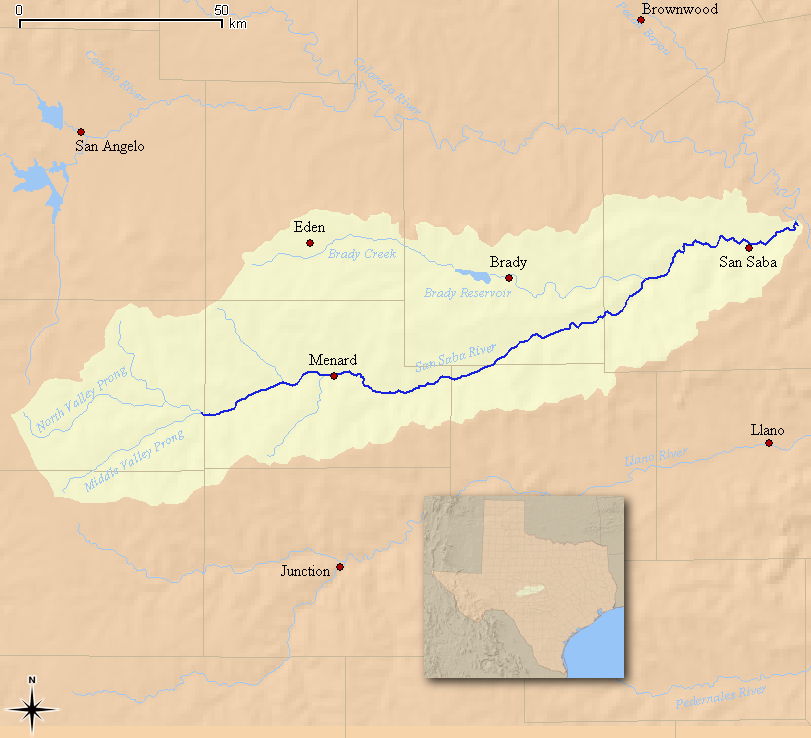

The San Saba River is a scenic waterway located on the northern boundary of the Edwards Plateau in Texas. Flows of sparkling, clear water course through limestone bluffs and hills, supporting fish, wildlife, and recreation. Through wasteful water use and unregulated pumping, irrigators are transforming a vibrant, pristine river into a dried-up riverbed.

The Texas Commission on Environmental Quality must enforce the law to ensure adequate flows are maintained. Further, the Texas Legislature should appoint a watermaster on the upper stretch of the San Saba River to better manage flows and protect the river long-term.

Threats to This River

Texas law provides that all natural surface water found in rivers is owned by the state and is held in trust for its citizens. There are no sealed meters and no accurate methods for the state to know whether irrigators around Menard, Texas, are exceeding their allowed limits.

Excessive pumping for agricultural irrigation has been diverting the river’s flow into a canal (where 30 percent or more is lost due to evaporation and leaks). Moreover, some irrigators place extremely shallow wells next to the river to pull water from the river under the guise of groundwater wells. This unregulated pumping in the last twelve years has almost dried up over 50 miles of the river for an average of five months of the year. This hurts downstream ranchers who need water, damages the river ecosystem, and negatively impacts the Austin chain of lakes.

While pumping is certainly legal by permitted landowners, such permit holders are required to leave a flow in the river sufficient to service the domestic and livestock users downstream. In 2011, after priority calls were made by ranchers, the Texas Commission on Environmental Quality (TCEQ) did the right thing and suspended pumping. The river filled up and flowed again despite irrigators’ claims that it was drought– not excessive pumping– that had dried up the river. When irrigators pumped the river dry again in 2012, the TCEQ inexplicably denied the priority calls from downstream ranchers, refusing to enforce the law because they claimed they did not feel the suspension would result in restored river flows. This position was puzzling since the flow returned to the river after the suspension in 2011– the year of the worst drought in more than 60 years.

Let's stay in touch!

We’re hard at work in the Southwest for rivers and clean water. Sign up to get the most important news affecting your water and rivers delivered right to your inbox.