Patapsco River

Say Can You See?

Without the Patapsco River, America wouldn’t have its National Anthem. Baltimore wouldn’t have its Inner Harbor and Maryland wouldn’t have its first state park. Talk about a powerful river.

The mouth of the Patapsco River forms Baltimore Harbor, the site of the Battle of Fort McHenry, where Francis Scott Key wrote “The Star-Spangled Banner” aboard a British ship during the War of 1812. Today, a red, white, and blue buoy marks the spot where the HMS Tonnant was anchored.

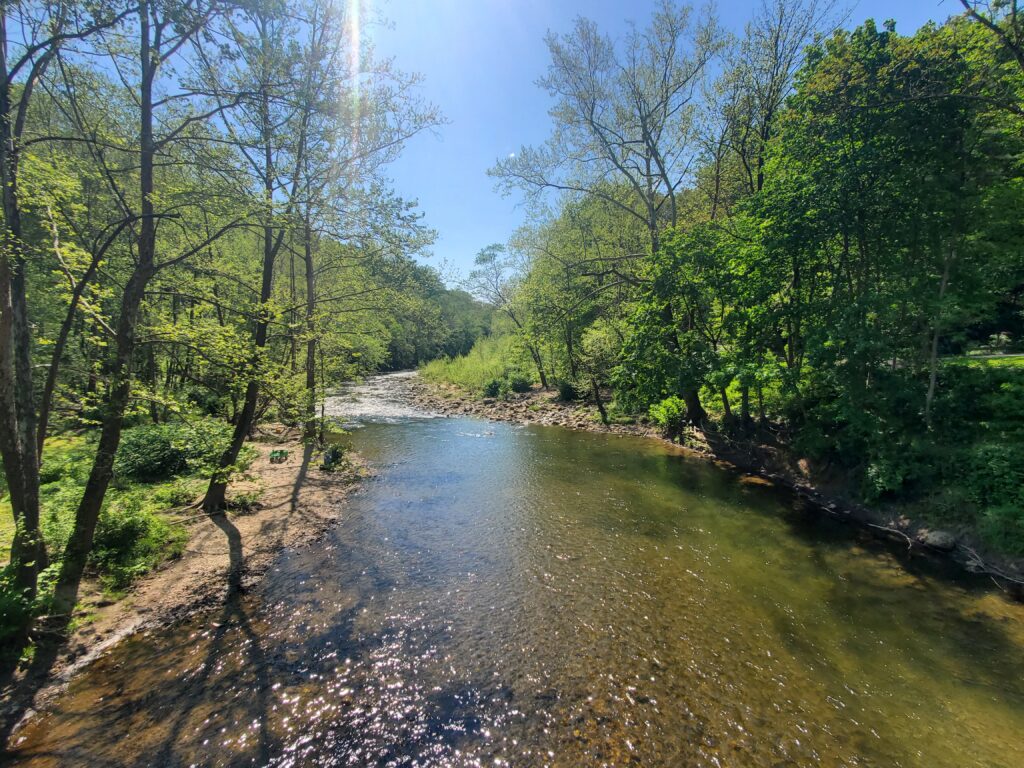

The river’s more popular association is upstream of Baltimore at Patapsco Valley State Park, however. With recreational opportunities including hiking, fishing, camping, canoeing, horseback riding, mountain biking, and picnicking along a 32-mile segment of the Patapsco and its branches, the park was officially celebrated as Maryland’s first in 2006.

The park’s history traces back more than a century, though, intimately intertwined with the river itself. Completion of Bloede Dam on the Patapsco in 1906 required protections to prevent silting from nearby farms, and the area was established as Patapsco State Forest Reserve in 1907 to protect the valley’s forest and water resources. Now known as Patapsco Valley State Park, it has grown to 16,000 acres highlighted by a rocky gorge cut by the river some 200 feet deep and laced with cliffs and tributary waterfalls.

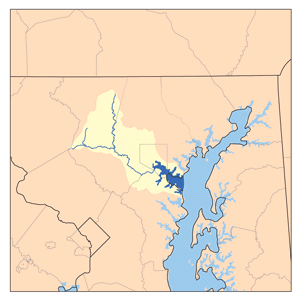

The river’s entire main stem flows fewer than 40 miles from Mariottsville through Elkridge, Ellicott City and other Maryland towns, drawing from a watershed of just 680 square miles, before it reaches the harbor and the Chesapeake Bay. Yet it remains one of the Baltimore area’s hidden jewels, providing the people of Maryland with a favorite fishing hole, Class I-II canoe and kayak rapids, trails to wander, and cool relief from the summer heat.

Did You know?

Francis Scott Key wrote the poem that later became the “Star-Spangled Banner” during the Battle of Ft. McHenry at the Patapsco River mouth in the Baltimore Harbor.

Bloede Dam, in Patapsco Valley State Park, was the first known instance of a submerged hydroelectric plant, where the power plant was actually housed under the spillway. The dam is scheduled for removal by July, 2017.

In 1999, final scenes of The Blair Witch Project were filmed in the Griggs House, a 200-year-old building located in Patapsco Valley State Park near Granite, MD.

What states does the river cross?

Maryland

Patapsco River Restoration Project Research

American Rivers has been working on restoring the Patapsco River through dam removal for more than a decade. Hit 'Learn More' for products, publications, and links to data repositories and presentations associated with this project.

The Backstory

Many historians consider the Patapsco River flowing through Baltimore one of the birthplaces of the Industrial Revolution, and dams built along the waterway were important sources of power. Bloede Dam was the first hydropower dam in the U.S. where the turbines were housed internally. However, as with many things, the Patapsco dams became obsolete as industry pivoted to other ventures.

Yet the old Patapsco dams continued to disrupt the natural function of the river and block passage for migratory fish like shad and river herring, and American eel. The dams also posed a safety hazard for paddlers, swimmers, and fisherpersons in Maryland’s most visited state park, which resulted in several deaths at Bloede Dam over the years.

Removing Bloede Dam

Bloede Dam essentially created a wall in the river that blocked fish. Visitors are now able to swim, boat, and potentially float nearly 17 miles of the Patapsco!

Working with the Maryland Department of Natural Resources, National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, Friends of the Patapsco Valley State Park, and many other partners, American Rivers has helped spur the removal of three of the Patapsco River’s four major dams—the Union Dam in 2010,the Simkins Dam in 2011, and the Bloede Dam in 2018—and is investigating the potential removal of the Daniels Dam, currently the farthest downstream dam on the Patapsco. Removal of Daniels Dam would complete the reconnection of more than 65 miles of the river and its branches, with only the upstream Liberty Dam remaining (currently providing water supply to the City of Baltimore and not slated for removal).

Although largely protected and hopefully soon to be reconnected, the Patapsco still suffers on its highly urbanized eastern end, which empties into Baltimore Harbor. Stormwater runoff and other forms of water pollution are exacerbated by aging infrastructure, often leading to hazardous water quality. Local infrastructure has been challenged by extreme weather events, leaking as much as 100 million gallons of sewage into the river during major storms.

Let's Stay in touch!

We’re hard at work in the Mid-Atlantic for rivers and clean water. Sign up to get the most important news affecting your water and rivers delivered right to your inbox.

The Future

American Rivers has been working for more than a decade on the Patapsco River Restoration Project which is benefitting water quality, river safety, native fish and wildlife, and the overall health of the river and the Chesapeake Bay downstream. This project is a priority for American Rivers and our partners because it addresses the three major crises impacting rivers across the country—biodiversity, climate change, and environmental justice.

The Patapsco River Restoration Project is more than just a dam removal project. It is an opportunity for collective visioning about the future of Patapsco Valley State Park. With millions of visitors annually, it is important to consider the needs of the park users and the local community. These projects build upon the great work of the Maryland Department of Natural Resources to support the park, as well as local groups such as Friends of Patapsco Valley State Park and Patapsco Heritage Greenway. American Rivers hopes to engage other groups as well, as we work towards a free-flowing Patapsco River.

Running through Ellicott City and ultimately down into Baltimore Harbor, the Patapsco River is uniquely situated to connect people and nature— healing the scars of an impaired industrial landscape and exploring how to live in harmony with the river and what that looks like for different communities. We hope to talk with a broader audience about this special place and help more people connect with the river.

For more information, contact Jessie Thomas-Blate with American Rivers at info@americanrivers.org.