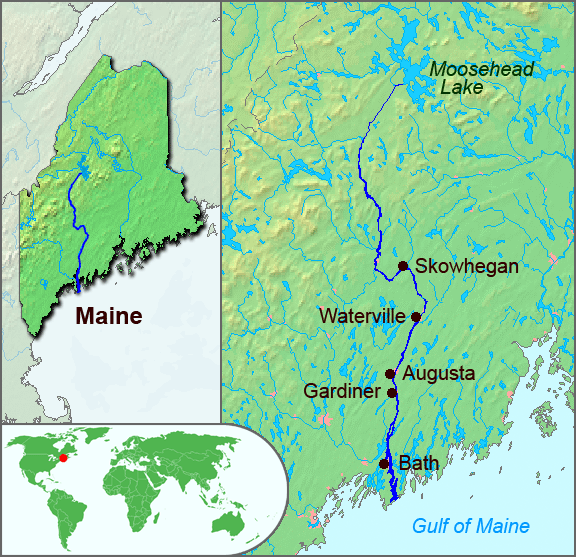

Kennebec River

The Kennebec is one of Maine’s major river systems that reaches from the Gulf of Maine high into the central heart of the state where Moosehead Lake feeds its headwaters. Its almost 6,000 square miles of watershed have sustained human communities for thousands of years. Like many other large coastal watersheds, the Kennebec River watershed supports habitats for all migratory fish species as well as a diversity of resident cold-water fish species. The natural topography and dams have created an important white-water economy on the upper reaches.

The watershed has been home to the Algonquin nations for millennia and early European settlers established forts and trading posts on the coast and near the fall-line in Augusta in the early 17th century.

Did You Know?

The last log drive on the Kennebec River was in 1977, decades after the practice has stopped on the other New England Rivers.

Merrymeeting Bay is the mouth of both the Kennebec and Androscoggin Rivers, which come together along with 4 other rivers to create the 17-mile long riverine estuary that drains to the Atlantic Ocean. The Bay is sustained by over 20,000 square miles of the state’s watersheds.

What State Does the Kennebec River Run Through?

Maine

Let's stay in touch!

We’re hard at work in the Northeast for rivers and clean water. Sign up to get the most important news affecting your water and rivers delivered right to your inbox.

Three Centuries of Damming the Kennebec River

Since European settlement, the Kennebec and many of its tributaries have been heavily dammed and modified to support mills, the timber industry, and industrial development including pulp and paper manufacturing. The upper reaches of the river support 9 hydropower stations, including Harris Station, the state’s largest hydropower generator. These dams and the many other small ones throughout the watershed served to support the economy of Maine for generations but also completely blocked off hundreds of miles of habitat for migratory fish, including some of the best habitat for the endangered Atlantic salmon on the Sandy River tributary.

That history began to change on July 1, 1999. It was a bright sunny day as the excavator slowly inched forward from the right bank of the river on the earthern berm built on top of the Edwards Dam. Hundreds of people watched the slow advance from both sides of the river, waiting for the signal. Given the green light the excavator operator deftly reached out and breached the timber crib structure that had blocked the river for over 160 years.

As the river poured through the initial breach the crowd cheered and in a bit of serendipity a number of short nose sturgeon leapt from the river as the flow dramatically increased. Cheers and leaps for the opening of the first dam on the river!

While a dam removal today may seem ordinary, in 1999 the demolition of Edwards Dam was a remarkable transition in how the federal government understood the balance between hydropower and free-flowing rivers. This removal was the first time that the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission authorized the removal of an active hydropower facility. Edwards Dam was a very small hydropower project that entirely blocked the Kennebec River, home to migratory fish including the endangered short-nose sturgeon and then recently listed Atlantic salmon.

Since 1999 many more dams have been removed throughout the watershed which has supported dramatic improvements in returns of migratory fish particularly in the Sebasticook River tributary. There is, however, much more work to be done as we seek to set a better balance between the dramatic ecological potential of this river and the energy and water needs of people and industry.

The removal of the Edwards Dam initiated an agreement for how upstream dams would be required to install or improve fish passage as migratory fish returns increased. This agreement signed by the dam owners and the coalition of environmental organizations – including American Rivers – set triggers for the dam owners to make improvements over time.

This agreement has proved challenging to all sides and has brought the many parties – owners, state and federal agencies, conservation organizations, and the public – to an essential standstill while federal licensing proceeds. Between 2021 and 2024 there has been on-going analysis, debate, and commentary on whether removal of four dams that are rated for a total of 45MW (a very small percentage of the state’s energy needs) just upstream of the former Edwards Dam site is a better solution than installing and operating new and modified up and downstream passage for all migratory species.

Whatever the results of this debate it will again set the Kennebec River as an example of how we think and act on behalf of rivers and the many communities – human and otherwise – that they support.

What’s new?

In the summer of 2024, the long-running conversation about how to balance uses on the Kennebec reached another milestone with a series of public hearings held by the National Marine Fisheries Service. These hearings were to receive comment on the Service’s proposed environmental impact statement that outlined plans for improvements in fish passage at four hydropower dams upstream from the former Edwards Dam site. American Rivers weighed in with the overwhelming majority of comments opposing installation of fish passage and recommending removal.

Partners Working in the Watershed

Maine Rivers

Atlantic Salmon Federation

The Nature Conservancy in Maine

Natural Resources Council of Maine

Conservation Law Foundation