Gunnison River

Thoroughly Western

From the heart of Black Canyon of the Gunnison National Park, it’s easy to appreciate the raw power of the Gunnison River. Monolithic walls of ebony schist, slashed by veins of granite, and carved to depths of more than 2,000 feet tell the tale of 2 million years of the mighty Gunnison relentlessly churning through mountains of stone.

The abyss was considered impassable by anything but the river until 1901, when a team of surveyors hiked through and mapped out plans for a 5.8-mile diversion tunnel that still shuttles more than 300,000 acre-feet of water from the Gunnison to a smaller tributary in the Uncompahgre Valley every year. Upstream of the Black Canyon, dams have impeded the once wild river’s passage, creating a series of storage and hydropower reservoirs, including Colorado’s largest at Blue Mesa.

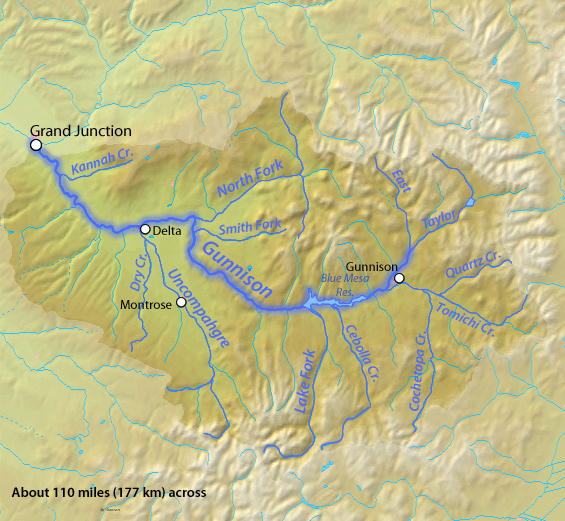

The state’s second largest river still has its moments, though. Between its headwaters along the Continental Divide and its confluence with the Colorado River near Grand Junction, the Gunnison alternates between pristine trout fisheries, public recreation areas, heritage ranches, and tumultuous whitewater fed by snowmelt runoff from some of the tallest mountains in the Rockies. Robust herds of mule deer and North American elk roam the surrounding forests and peaks with bears, mountain lions, and bighorn sheep.

Below the town of Gunnison, Blue Mesa Reservoir holds trophy mackinaw and the state’s largest population of kokanee salmon, which migrate upstream every autumn to the delight of anglers and eagles alike. Downstream of the dams, world-class rock climbing, paddling, scenery and Gold Medal trout fishing draws visitors from around the country to the Black Canyon and more accessible Gunnison Gorge just above the confluence with the river’s North Fork.

The focus is on agriculture in the lower basin, delicately balanced against the needs of several species of fish listed under the Endangered Species Act. By the time it connects to the Colorado River, the Gunnison will have drained nearly 8,000 square miles of rugged terrain in rural western Colorado, though its renown reaches far beyond.

Did You know?

Among all the tributaries to the Colorado River, only the Green River is bigger than the Gunnison in terms of water contributed.

The Black Canyon of the Gunnison was named a national monument in 1991 before Congress declared it a national park in 1999.

Although its headwaters originate along the Continental Divide, the Gunnison formally begins at the confluence of the Taylor and East Rivers south of Crested Butte.

Both the river and town are named for Lieutenant John Gunnison, an engineer sent to survey a railroad route across the Rockies in 1853.

other resources

Check out these other resources to learn more about the river:

What states does the river cross?

Colorado

The Backstory

To protect “the roar of the river,” President Herbert Hoover declared the Black Canyon a national monument in 1933. In 1999, Congress declared it a National Park. Though beautiful and partially protected, the Gunnison River has been starkly impacted by man nonetheless.

Three dams operated by the Bureau of Reclamation just upstream from the park have severely altered the natural flow of the river. The Aspinall Unit, as the dams are collectively known, inundated more than 40 miles of prime native trout waters to allow more consistent control of the river’s water for irrigation and hydropower.

Let's stay in touch!

We’re hard at work in the Southwest for rivers and clean water. Sign up to get the most important news affecting your water and rivers delivered right to your inbox.

After being named America’s Most Endangered River® in 1991 and returning to the list at No. 4 in 2003, a coalition of stakeholders and litigators hammered out a decree to protect the natural values of the Black Canyon in 2008. Decades of conflict eventually resulted in water rights that now promise a spring peak flow, shoulder flows and base flows critical to the health of the river.

The Future

Like other rivers in the Southwest, the Gunnison suffers from periodic drought, placing stress on agriculture, fish, and habitat. But water users throughout the basin are proactively addressing these challenges by installing water-saving irrigation infrastructure, investigating water sharing opportunities, and promoting in-stream flow protections, particularly at critical headwaters. Delta County, in the basin, is piloting a new agricultural hydropower program focused on pressurized sprinkler irrigation rather than flood irrigation in order to spur water conservation.

The Gunnison River is one of the last major sub-basins in Colorado that has not been diverted to provide water to ballooning Front Range communities, marking it as a potential target for the future. A major diversion out of the basin would have severe impact on fish, wildlife, agriculture and a growing recreation economy. For now though, the resilient river endures.