Verde River

Turning water into wine

The Verde River is already about halfway through its 180-mile journey before it really becomes recognizable as a river. But by the time it accumulates enough of Arizona’s patchy precipitation about 30 miles southwest of Flagstaff, it blossoms into a perennial gem that passes through one of the most beautiful places on earth.

Just beyond the burgeoning Sedona-Verde Valley, the Verde grows large enough for mild whitewater boating in a unique and breathtaking landscape rich with wildlife and steeped in history.

Several stretches are ideal for canoeing, kayaking, or SUP adventures, but maybe none more enticing than the 40-mile segment recognized as the first of only two Wild and Scenic Rivers in Arizona, along with downstream tributary Fossil Creek.

The shallow, rugged canyon below Beasley Flats combines slightly spicier whitewater with stunning desert scenery rimmed by red rock bluffs and tiered with cactus-covered hillsides above a lush riparian corridor along the river’s edge.

Making its way into the Mazatzal Wilderness, Arizona’s largest, the Verde is a magnet for waterfowl and dozens of other bird species dependent upon its vital oasis amidst arid desert uplands. The high-quality habitat supports more than 50 threatened, endangered, sensitive, or special status fish and wildlife species.

Hikes galore offer chances to see ancient cliff dwellings in side canyons and trails that climb nearby ridges, including Montezuma Castle National Monument near Camp Verde. Like the early inhabitants that first made their home there, newer communities surrounding the river corridor depend upon the Verde still. Rather than irrigating subsistence crops, though, the modern focus is on tourism established in part through river recreation and a growing local wine industry, high yield harvests that keep more water in the river than row crops like cotton and alfalfa that have depleted the resource historically.

Did You know?

Wine production in the Verde Valley generates about $25 million annually, employs over 100 people and accounts for $6.5 million in spending at tasting rooms, vineyards and wineries.

Grapes are an ecologically sound crop using 1/10th of the water per acre that cotton or other row crops consume.

The Verde’s riparian and associated upland habitat supports over 60 percent of the vertebrate species that inhabit the Coconino, Prescott and Tonto National Forests.

The earliest hydropower plant in Arizona (now decommissioned) is located in the Verde corridor, as are the remains of one of the state’s first tourist developments, the Verde Hot Springs Resort.

WHAT STATES DOES THE RIVER CROSS?

Arizona

The Backstory

Much of the Verde Valley’s history can be traced back to a legacy of copper, gold, and silver mining in the surrounding hillsides, with little emphasis on the river once the hunter-gatherer Hohokam and Sinagua people disappeared. Market collapses led to yet another cultural shift as the spirit of mining towns abandoned in the 1950s has been rekindled through eco-tourism and a new-age metaphysical subculture.

Where nearby Sedona and the Oak Creek tributary of the Verde have long been on the tourism map, the greater Verde Valley has only recently begun to come into its own. The influx of visitors is a big boon to local economies, but it can put significant strain on natural resources already stretched thin by overuse and excessive withdrawals for outdated agriculture and growing municipalities.

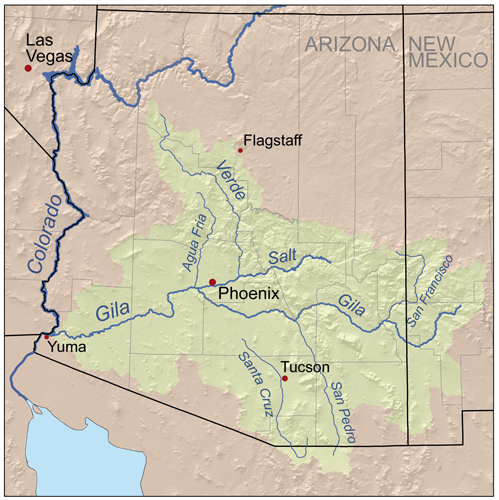

Downstream, booming southwestern cities with scarce water sources render rivers like the Gila, the Salt, and its largest tributary, the Verde, almost entirely used up by the time they pass through the megalopolis of Phoenix. Should water levels in Lake Mead continue to drop, the remainder of the Verde River could easily become a target for central Arizona water supply.

The Upper Verde River

American Rivers and partners are hard at work in efforts to designate the Upper Verde River as Arizona’s next Wild and Scenic River. Check out these videos from Wild and Scenic Rivers Hill Week 2024 when the Upper Verde Wild and Scenic River Coalition met with members of Congress to discuss making this designation happen!

The Future

In the wake of Wild & Scenic designation, small towns like Jerome, Clarkdale, Cottonwood, and Camp Verde have come to embrace the river and are actively seeking ways to connect it to their communities as a lifestyle amenity. Those efforts are paying off.

Let's stay in touch!

We’re hard at work in the Southwest for rivers and clean water. Sign up to get the most important news affecting your water and rivers delivered right to your inbox.

Recognizing the economic benefits and lifestyle draw of a healthy river, even local businesses are getting on board. Mining conglomerate Freeport-McMoRan has set aside a conservation easement on the upper Verde River as a contribution to the quality of life the surrounding community hopes to maintain and carry into the future.