Teton River

A Tale of Two Rivers

The Teton is the last major free-flowing river in eastern Idaho. And apparently it intends to stay that way.

The 81-mile tributary of the Henry’s Fork that drains the placid Teton Valley along the Idaho-Wyoming border reasserted its stature as a wild, free-flowing river in 1976, when the Teton Dam failed catastrophically as it was being filled for the first time. The ensuing deluge claimed the lives of 11 people and 20,000 head of livestock while causing $2 billion in property damage as it gushed downstream. It is considered one of the worst dam failures in U.S. history.

The force of the failure took an incalculable toll on native fish and wildlife in the Teton River Canyon as water and debris washed away riparian zones and reduced the canyon walls. The river canyon has since recovered to provide vital habitat for native Yellowstone cutthroat trout along with the thousands of elk, mule deer, and trumpeter swans that overwinter in the canyon.

What remains is a Western treasure that serves as one of the last strongholds for imperiled Yellowstone cutthroat trout. The tranquil upper valley draws drift boats and dry-fly fishermen, while the rugged and scenic lower river supports a tremendous, albeit lightly used wild-trout fishery and stellar whitewater boating during the high water months.

Did You know?

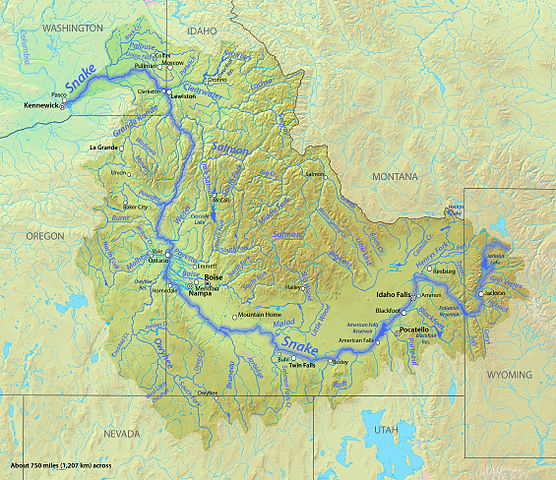

Although it flows almost entirely in Idaho, the Teton River actually originates in Wyoming, on the west side of the Teton Range.

The Teton River bifurcates into two distributaries—the Teton and South Fork Teton—that merge with the Henry’s Fork at two different locations.

When the Teton Dam failed in 1976, an estimated 80 billion gallons of water scoured the town of Rexburg, ID, site of the Teton Flood Museum.

WHAT STATES DOES THE RIVER CROSS?

Idaho, Wyoming

The Backstory

Geologists and engineers recognized how poorly suited the porous soil and rock at the foundation of the Teton River Canyon is for a dam site, but that didn’t prevent the U.S. Bureau of Reclamation from building the earthen Teton River Dam there anyway. Nor did it dissuade the Idaho Legislature from appropriating $400,000 in 2008 to fund a study on rebuilding the Teton Dam, the most recent of many attempts to do so since the original dam failed. Technically, it’s still an authorized dam site.

Let's Stay in Touch!

We’re hard at work in the Northern Rockies for rivers and clean water. Sign up to get the most important news affecting your water and rivers delivered right to your inbox.

Beyond the obvious risks, rebuilding the Teton Dam would destroy a tremendous wild-river recreational resource that thrives in large part due to the vital habitat it provides for Yellowstone cutthroat trout and countless other wildlife species. The dam would also create a barrier to higher elevation tributary streams, preventing fish from reaching the coldwater habitats they will need as the climate warms.

The Future

Fortunately, this time around the Bureau of Reclamation has placed rebuilding the Teton Dam low on its list of projects that can meet eastern Idaho’s future water supply needs without inflicting serious environmental damage. American Rivers also took part in the recent study of potential dam sites for the region and helped quash the idea of rebuilding Teton Dam, at least for the time being. Until it is permanently protected, threat of a new dam still lingers.

That’s why we’re advocating for a Wild and Scenic suitability study to determine if the Teton River Canyon and three of its major tributaries (Badger, Bitch, and Canyon creeks) should be added to the National Wild and Scenic Rivers System. Wild and Scenic designation would forever protect them from new dams, dewatering and other threats. The U.S. Bureau of Land Management (BLM) plans to begin the study in 2016.

Meanwhile, improved water-conservation measures, aquifer recharge and creative water marketing strategies remain effective options for improving water supplies in lieu of a dam.