Whether you’re looking for something new and entertaining to do outside or need an excuse to get out and enjoy the river, we’ve got you covered! And if your boss has any questions – tell them to contact us, we’ll handle it.

Click each image to download and print to use as many times as you wish!

Happy Summer!

Imagine leaving the Bay Area heading east, cruising past the urban and suburban sprawl, and starting to climb through the foothills of the Sierra Nevada. As you curve along the two-lane highways that bisect the wilderness, Ponderosa pine and Douglas fir shield your view. Great mountains carpeted with evergreens and granite caps loom above the horizon. Hidden within the trees and peaks lie the mountain meadows of California.

If you pay a visit to one of California’s high-elevation mountain meadows, you might hear an unusual sound. Not just the trilling of an alpine bird or the rustle of wind through the pine needles, but the mechanical hum of heavy machinery. Don’t worry! All is going according to plan. American Rivers, alongside a range of devoted partners, were restoring four mountain meadows this summer.

These meadows are critical to the hydrology of the landscape and provide a unique home to native plant and animal species, anchoring soil and storing groundwater. While they may be small in area, covering 191,000 acres of the mountain range, mountain meadows are critical to the health of California’s source waters which provide clean drinking water to more than 75% percent of Californians. Beyond this, they provide essential habitat, recreational opportunities, and climate change resiliency. However, around 50% of the Sierra Nevada’s mountain meadows are significantly degraded, reducing their critical ecological function and benefits.

American Rivers leads meadow restoration from start to finish, including initial assessment to identify meadows in need of restoration, design and permitting, on-the-ground restoration, and monitoring to quantify project benefits. Planning is complicated and time consuming, often taking three years of pre-work prior to on-the-ground work. This season, the fruits of these efforts paid off, and American Rivers implemented four meadow restoration across the Sierra, contributing to landscape scale restoration!

Calf Pasture meadow (30 acres) is in Eldorado National Forest (ENF), in the headwaters of the South Fork American River. For this project, we fully filled a severely incised stream channel within the meadow, which was up to eight feet deep, to reconnect the channel and floodplain. Reconnecting this channel to its meadow floodplain restores the natural hydrology of the system, which improves groundwater storage and species habitat, as well as increases wetland plant cover and diversity of pollinator species. Calf Pasture restoration is part of a broader effort to accelerate the pace of restoration in Eldorado National Forest. To bolster internal capacity, American Rivers fostered ENF staff participation in the full lifecycle of the project, from identifying projects, to completing planning, and finally implementation. This project will streamline additional meadow restoration efforts and build momentum for future work within ENF. Calf Pasture Meadow Restoration is a collaborative effort undertaken alongside ENF, contractors, volunteers, and funded by the National Fish and Wildlife Foundation (NFWF).

Confluence Meadow (140 acres) is in Lassen National Forest, in the Pine Creek watershed. The Pine Creek watershed is home to the endemic Eagle Lake Rainbow Trout (ELRT), a California Heritage Trout and a Species of Special Concern. In 2015, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (USFWS), California Department of Fish and Wildlife (CDFW), and U.S. Forest Service (USFS) released a strategy guidance document called the Conservation Agreement for the Eagle Lake Rainbow Trout, which identified meadow restoration as a crucial ELRT recovery action. American Rivers is working collaboratively with the Pine Creek Coordinated Resources Management Program (CRMP) to advance meadow restoration in the Pine Creek watershed to enable natural spawning and reproduction of ELRT. First, American Rivers evaluated all the meadows in the watershed using the sites for restoration. This year, American Rivers restored Confluence Meadow by completely filling the eroded Pine Creek channel, which will enable floodwaters to spread out and soak in, replenishing groundwater and prolonging summer streamflow, which will improve habitat and increase baseflows in the critically dewatered Pine Creek for natural ELRT spawning. Confluence Meadow Restoration is a collaborative effort undertaken alongside Lassen National Forest, the Pine Creek CRMP, and funded by the CA Wildlife Conservation Board (WCB).

Log Meadow (18 acres) is in Sequoia and Kings Canyon National Parks, in the Middle Fork Kaweah watershed. The meadow is in Sequoia National Park’s Giant Forest, one of the world’s most important sequoia groves based on the land area, size of sequoias within the grove, and current conditions. To restore the meadow, we hired hand crews (California Conservation Corps, CCC and American Conservation Experience, ACE) to fully fill the main gully with onsite vegetation. The crews scythed approximately 7 acres of the meadow, dried out the vegetation, and used hand balers to create hay bales. Then, the hay bales were packed into the main gullies until flush with the meadow floodplain, which effectively allows spring floodwaters to spread out and soak in, reducing peak flows and replenishing groundwater and prolonging streamflow in the summer. The larger goal of this project was to develop and test hand-labor meadow restoration techniques to aid and inform future work in designated Wilderness where motorized vehicles and machinery are not permitted. Log Meadow Restoration was a collaborative effort undertaken alongside Sequoia and Kings Canyon National Parks, the CCC and ACE, and funded by the CA Department of Fish and Wildlife and the CA Wildlife Conservation Board.

Faith Valley (200 acres) is in Humboldt-Toiyabe National Forest, in the Upper West Carson watershed in the eastern Sierra Nevada. American Rivers and partners are working to protect and restore 110 acres of the meadow, as well as enhance recreation opportunities. Faith Valley has a resident beaver population that is helping to restore the meadow. We are using Low Tech Process Based Restoration techniques that mimic natural beaver dams, called beaver dam analogs (BDAs) to accelerate restoration. Both natural dams and BDAs will raise the water table and capture sediment to reconnect the stream channel of the West Fork Carson River with its meadow floodplain, allowing for enhanced infiltration and groundwater storage and restored habitat for birds and aquatics. The project is being implemented over two seasons so that we can observe and learn from the initial pilot set of BDAs. In 2022 we installed 14 BDAs, as well as a rocked grade control structure to anchor the overall project. In 2023 we will install the remaining BDAs for holistic restoration, as well as repair the adjacent OHV road to protect the meadow and enhance recreation opportunities. Faith Valley Meadow Restoration is a collaborative effort undertaken alongside the U.S. Forest Service, Humboldt-Toiyabe National Forest, Alpine Watershed Group, Institute for Bird Populations, Friends of Hope Valley, and Trout Unlimited.

Restoration of these four meadows, totaling 388 acres, contributes directly to the goals of the Sierra Meadows Partnership, a landscape-scale collaborative of meadow restoration practitioners aiming to restore and protect 30,000 meadow acres by 2030. California’s sourcewaters are experiencing the comprehensive impacts of anthropogenic climate change. Meadow restoration and healthy meadows are capable of addressing the impacts of climate change by tempering peak flows, sequestering greenhouse gasses, supplying groundwater storage, and providing climate refugia. We need to keep supporting the organizations, tribes, and land managers that are advancing nature-based solutions and on-the-ground work towards audacious landscape-scale goals that define alliances like the Sierra Meadows Partnership.

The cicadas drone as Joey and I chat over coffees on a gorgeous late-summer morning along the Oconaluftee River in Cherokee, North Carolina. A few leaves on the trees are starting to turn yellow and spiral their way down to the river as the water whooshes downstream.

Joey, an enrolled member of the Eastern Band of Cherokee Indians, is tall and energetic, and he uses his hands when he’s talking about something he’s excited about — like removing the Ela Dam from the Oconaluftee. Joey is also the Secretary of Agriculture and Natural Resources for the Tribe. And he’s not reluctant to pick up the phone and ask the owner of a hydropower dam if they would like to discuss dam removal. But more about that in a minute.

Joey grew up on the Qualla Boundary, a small part of the historic Cherokee territory, which once sprawled from eastern Tennessee across western South Carolina, northern Georgia, Kentucky, western North Carolina, and Alabama. Both his parents worked for the Tribe. He left Cherokee to get his education and returned, first as an intern in the Natural Resources department, then after graduate school, as the appointed Secretary.

“Growing up in this community, I was always playing in the river. That’s my earliest memories, 5-years-old, going to the river, swimming, being there all day, ‘cause there wasn’t a lot going on. We didn’t have a lot of money, so you went a played in the river all day. Make it a family affair, friends, cousins. Growing up, that was expected during the summer.”

The Ela dam separates the Oconaluftee River from the rest of the Tuckasegee watershed and has since 1925 — almost 100 years. Because of this one dam, the entire Qualla Boundary and parts of Great Smoky Mountain National Park are entirely blocked off from their historic drainage.

The dam represents what Tommy Cabe, Eastern Band of Cherokee Indians’ Tribal Forest Resource Specialist, calls “a thorn in the leg of Long Man.” The Cherokees have always viewed the river as “Long Man (Ga-na-hi-da A-sga-ya),” whose head lies in the mountains and whose feet lie in the sea. Long Man is a sacred figure who provides water to drink, cleanliness, food, and numerous cultural rituals tied to medicine and washing away bad thoughts and sadness.

For example, sicklefin redhorse, a fish only recently known to Western science, have long been a staple in the diet and culture of the Cherokees. For almost 100 years, this fish has not been able to reach the Qualla Boundary because of the dam. This fish is regionally migratory and runs up rivers like the Oconaluftee River to spawn. Without access to upriver spawning habitat, this unique Southeastern species will die out.

With biodiversity loss increasing, especially in aquatic systems, restoring access to free-flowing rivers is more important now than ever. The more habitat available, the better chance freshwater species like sicklefin redhorse and the federally endangered Appalachian elktoe mussel (Alasmidonta marginata) have of adapting to changes in their habitat brought on by climate change.

After an accident that released sediment from Ela dam that smothered the river life downstream of the dam, Joey kept coming back to the same question: “What if we could remove this dam?” For the nearly 10 years of the Eastern Band of Cherokee Indians’ and American Rivers’ partnership, Joey, Mike LaVoie, Dr. Caleb Hickman, and I have joked about how cool it would be to remove the Ela dam and reconnect 500 miles of natural habitat. But we didn’t really think it was feasible … until Joey picked up the phone and called the dam’s owner, Northbrook Hydro.

Immediately I told him, “American Rivers is with you 100 percent on this project. Whatever you need, we’re here.”

After Northbrook Hydro was on board to explore removal, Joey submitted a resolution to Tribal Council to empower him and his department to develop a coalition to remove Ela dam. The coalition, which includes a laundry list of state, federal, and nonprofit partners, continues to meet biweekly since the Tribal Council passed the resolution in February 2022.

The project to remove Ela dam is still in the early stages and requires several more hurdles before removal can happen, including that the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission surrender the hydropower license, then design, permitting, and finally demolition. And many partners are essential in moving the project forward: Mainspring Conservation Trust is leading on the land-acquisition, American Rivers will manage the actual dam removal, and the Eastern Band of Cherokee Indians is leading the coalition with sheer will and determination. Big credit to Northbrook Hydro for entertaining a once-outlandish idea.

“My value around water comes from my dad working in wastewater for 16 years. We all flush the toilet every day and don’t think twice about it. All that waste has to be dealt with, that water is separated out to put back in the river as good a quality. Those are things I learned early on and have been reflecting on since working on this project with y’all. I can’t say I was a river advocate growing up, but I knew I wanted a clean river.”

Now, under Joey’s leadership, the entire Oconaluftee River, the lifeblood of the Cherokees, will be reconnected once more.

“Removal of this dam only starts to restore parts of our cultural identity.” Joey smiles and says, “What’s the next big one?”

American Rivers’ story began in 1973, when a group of conservationists, policy experts, and river lovers, alarmed by the rate that rivers were being dammed and destroyed, decided to create an organization to protect our nation’s last free-flowing rivers. At a meeting in Denver, somebody threw $10 on the table. And another and another, until there was a small pile of money. American Rivers was born out of passion and $4,100.

That passion has led to some truly remarkable victories for rivers over the past five decades. Together with our partners and supporters, we have safeguarded over 150,000 miles of rivers and over 3 million acres of riverside land. We have organized local and national partners to drive policies that protect drinking-water sources for tens of millions of people. We have donned hard hats to blow holes in 150-year-old dams, put water in dried-up river reaches, and created river-friendly policies.

The only way an organization can survive for 50 years and achieve the level of impact American Rivers has enjoyed is with consistent support from dedicated people who believe in its mission. The health of rivers across the country has improved because of you and the thousands of staff, partners, Board members, donors, volunteers, and allies who have found a home in this organization. Thank you for standing by our mission to protect wild rivers, restore damaged rivers, and conserve clean water for people and nature.

Despite our incredible progress, the challenges ahead are dire. Our rivers are increasingly threatened by climate change, harmful dams, pollution, drought, floods, and outdated laws. Perhaps the greatest threat is simply a lack of awareness of how important rivers are to our lives.

American Rivers has always tackled challenges head-on. Now, because of these growing threats, we’re picking up the pace and scale of our work on rivers nationwide. By expanding our local connections, we will work on more rivers and with more communities around the country — particularly those that have been historically sidelined from decision-making. We are also connecting local river advocates across communities to ensure they have the tools, support, and community to get the job done. Finally, and maybe most importantly, we will double down on our commitment to collaboration, pragmatism, and results.

These strategies, with your support, will directly improve the health of rivers and water. Here’s how:

Protect 1 million miles of river.

We’re committed to restoring and protecting 1 million river miles in the United States, from remote mountain streams to urban waterways. To do this, we are advocating for federal and state protections for some of our healthiest, most scenic rivers, as well as rivers in urban and suburban areas. We are also working with communities experiencing more frequent and damaging flooding and droughts to reconnect their rivers to their headwaters and floodplains. These rivers, and the watersheds that feed them, provide recreation, clean water, and natural habitat for the benefit of all of us.

Remove 30,000 harmful dams.

Free-flowing rivers promote healthy habitat for wildlife, reduce flood risk to communities, and support cultural traditions. There are more than 90,000 inventoried dams (and up to 400,000 dams total!) in our country. Up to 85 percent of them are unnecessary, harmful, and even dangerous. We must remove thousands of them quickly. Our work to remove dams has been central to our impact over the past decades and will be even more important as we work to restore rivers in the decade ahead. Because removing a dam is the single most impactful way to secure a rivers’ future health.

Ensure clean water for every community.

Over the past 50 years, American Rivers and partners have protected drinking water sources for tens of millions of people. Millions more are vulnerable to the health impacts of water pollution. Black, Indigenous, and People of Color, and Tribal Nations are more likely to be impacted by environmental hazards and are more likely to live near contaminated lands and be affected by unhealthy water. Everyone deserves clean water. At American Rivers, we’re increasing our community engagement so that no communities are left behind.

Champion a powerful river movement.

American Rivers has always been known for our ability to work with local advocates and partners from both private and public sectors to do what’s best for rivers and the people and wildlife that depend on them. We know that the challenges to rivers are increasing dramatically. We need an even stronger river movement to face those challenges. By deploying more American Rivers staff in the field, we will double our efforts to bring more local support to the cause of rivers and to work with others to coalesce a movement that restores and protects the rivers we treasure.

Are these goals ambitious? Absolutely. But the growing threats to our rivers require from us our ambition, ingenuity, and resolve.

This year, we are introducing a new tagline for the organization: Life Depends on Rivers. Along with our new logo, the tagline could not be a more appropriate description of the threats rivers face and the importance of our work.

Fortunately, rivers are resilient. Humans are, as well. Enabling rivers to heal is our best hope to address climate change, protect freshwater species, and equitably provide the benefits of healthy rivers and clean water to everyone. The way forward must include greater partnerships, community engagement, and growing a movement to protect rivers, from mountain streams to urban waterways.

So, it is with gratitude for your past support and enthusiasm for what comes next that I invite you to join us as we embark on the next 50 years of action for the rivers all life depends upon. Onward!

This year, 2023, marks the 50th anniversary of American Rivers. As we celebrate our successes, we are also launching a bold new vision with ambitious goals. The challenges facing rivers are huge. Rivers all across the country are threatened by pollution, dams, and increasing droughts and floods. Perhaps the greatest threat to our rivers is simply lack of awareness of how important they are to our lives. To achieve our new vision, American Rivers must inspire greater action and reach more people nationwide.

As one of the nation’s premier organizations dedicated to saving rivers, we must be compelling and inclusive. We need to embody both urgency and optimism. We need to be a strong voice for how essential rivers are to our health and survival. And we must capture the joy, beauty, and potential rivers offer.

You can see this reflected in our new tagline: Life Depends on RiversSM. Rivers are the circulatory system of our environment and communities: We simply can’t survive without them.

Nearly all of us live within a mile of a river, but too few know what that river provides. Rivers give us clean drinking water. Rivers are home to plants and animals. Water from rivers grows our food. Rivers make our cities more vibrant. And, rivers are fun!

Our new logo evokes the essential need for all of us, whether you live in the mountains, the city, or anywhere in between, to connect more completely with the water and rivers that you and all of nature depend on.

We hope our new look inspires you to connect more with your own rivers, and to get involved with American Rivers. Please join us on January 25 for our 50th anniversary online event. Help celebrate the last 50 years and launch American Rivers’ new strategic vision. The event is free and open to the public – register here.

Brian Wong has a lot on his shoulders. A third-generation farmer, Wong grows crops — including nearly extinct heritage grains like white Sonora wheat — on 4,500 acres in the heart of the parched Sonoran Desert, about 25 minutes northwest of Tucson, Arizona. Bakeries, restaurants, breweries, and flour mills as far away as Minnesota and Florida rely on his grain to sustain their own businesses.

Wong’s BKW Farms is among the 80 percent of the state’s agricultural producers that rely on the Colorado River to irrigate their crops. And with the Colorado at precariously low levels, his family business faces its largest challenge in nearly 85 years. “We have a great understanding of and place great importance on water,” Wong says. “Water is something you need in almost every aspect of agriculture. Everything we grow is irrigated. We need to have a water source to put on the crops so we can continue growing food.”

All of the water irrigating Wong’s farm arrives via the Central Arizona Project (CAP), a 336-mile canal system that shuttles Colorado River water to customers throughout the state. Altogether, the Colorado irrigates 5 million acres of farm and ranch land across seven Southwestern states and Mexico. It supplies 40 million people with drinking water and supports a $1.4 trillion economy.

But climate change, extreme drought, and explosive population growth are taking an enormous toll on the river. The Colorado and its two largest reservoirs, Lake Powell and Lake Mead, dwindled to calamitously low levels in 2022, forcing the U.S. Department of the Interior to declare, for the first time in history, a Tier 1 Water Shortage. The declaration triggered deep cuts in the volume of Colorado River water delivered to Arizona, Nevada, California, and Mexico. Arizona agriculture took the biggest hit because CAP is on par to get 30 percent less water from the shrinking river. Even deeper restrictions will go into effect in 2023, with cities and Tribes shouldering more of the brunt.

Alongside farmers like Wong, American Rivers is urgently working together with partners at utilities, municipalities, and conservation groups to fix the massive imbalance between demand and a shrinking Colorado River.

From working with ranchers to restore habitat in the river’s headwaters, to encouraging municipalities to use less and eliminate unnecessary uses of valuable Colorado River water, to working on new guidelines for long-term management of the river, American Rivers is involved in decisions that span 1,700 miles of the Colorado River, from its headwaters in Colorado to its delta in Mexico.

“The hard truth is, there just isn’t enough water to go around for everyone,” Wong says.

We have to learn to live with a smaller Colorado River. Wong says the way forward is by partnering with advocates like American Rivers, who work with policymakers and stakeholders to elevate stories and shape water-management strategies into the future.

The bottom line is that “I” doesn’t work. We all rely on rivers, and water, and their continued existence. Our future demands that we invest boldly and immediately in strategies that will work — and that will build for all of us the kind of future we want for our children.

Sometimes you don’t know you want to protect something until you’re threatened with losing it. That was the case for communities of southern Maine, where the York River and its tributaries meander through the communities of York, Kittery, Eliot, and South Berwick, feeding rich salt marshes and hardwood forests that blanket the landscape between the hills and the coastline.

For many, the river was a source of enjoyment. It was a fun afternoon canoe outing during migratory bird season. It was nice to have.

But as metropolitan Boston has grown, city dwellers have moved up the coast in search of access to the outdoors and a more affordable lifestyle. Coastal southern Maine now faces the highest development pressure in the state. And that means more buildings, more pavement, and more yards overtaking and fragmenting areas that used to be forest and community greenspaces fed by the York River.

Concerned that development would damage the character of the region and the river’s health, all four York watershed communities worked with Congress and the National Park Service to establish a local committee to explore possible protection for the river under the Wild and Scenic Rivers Act.

Soon, the communities were learning about water quality, species that live in or beside the river, impacts of climate change on the watershed, Indigenous history going back 3,000 years, and colonial history. Their interest was sparked — and so was their passion to protect the York for current and future generations.

The York River carries enormous regional significance. It is home to nationally recognized historic sites and more endangered and threatened species than any other area in the state. The watershed provides clean drinking water to local communities and to the nearby Portsmouth Naval Shipyard, which employs thousands of area residents. And the river’s green spaces act as a natural buffer to the impacts of a warming climate, protecting against storm surges, rising sea levels, and nor’easters that erode the shorelines.

For three years, the York River Wild and Scenic Study Committee worked to understand why its watershed deserves Wild and Scenic protection. The committee held 60 public meetings and river walks to educate residents about the resource in their backyard. In the end, residents of York, Eliot, South Berwick, and Kittery were convinced: When asked whether they supported formally designating 30.8 miles of the York and its tributaries as Wild and Scenic, residents overwhelmingly answered “yes.”

The National Park Service sent the York River Wild and Scenic Study Committee’s report to Congress, and legislation is making its way through the congressional approval process. It has bipartisan support.

A Wild and Scenic York River would be a partnership between the community and the federal government, with the communities running the show.

In the case of the York and other Partnership Wild and Scenic Rivers, designation will protect these nationally significant rivers from dams or other federally permitted projects that would pollute, confine, or threaten the river. For these partnership rivers, local governments continue their responsibility for managing river use and activities on private lands along the river through local ordinances, zoning, and regulations. The role of the National Park Service is to prevent any new dams on the river and to provide technical and financial support to the local stewardship group working to protect and restore the river.

Community management is a model that American Rivers believes is one of the most sustainable ways to provide long-term protection for rivers that flow through private lands. The process creates local support that is essential for conservation efforts to take hold and last. Partnership Wild and Scenic River designations put the power in the hands of local residents. That’s why American Rivers co-founded the Wild and Scenic Rivers Coalition, an alliance of more than 60 river groups nationwide that helps support nascent community groups that are exploring river protection options for their favorite local rivers.

If the river movement is to protect 1 million miles of rivers in the coming decade, we’ll need to employ all of the tools in our toolkit. Local leaders and communities like those on the York River can play a powerful role by embracing the Partnership Wild and Scenic River model. American Rivers and the Wild and Scenic Rivers Coalition will be there to help advise them and ultimately build momentum in the halls of Congress for river protection bills like the York. As we help communities grow on-the-ground support, we will also learn from them as they mount their own campaigns. Together, we can build a movement of river champions working hand in hand to protect our favorite rivers.

Update: The York River received protection as a Partnership Wild and Scenic River as part of the $1.7 trillion spending bill passed in December 2022. We congratulate the York River Wild and Scenic Study Committee and all of the individuals involved in protecting this beautiful, important waterway.

Part of our ethos is building a multiracial, multicultural environmental movement on behalf of the water. And we’re looking to do that regionally. We’re looking to do that within our own organization and within our city

Brenda Coley, co-executive director, Milwaukee Water Commons

Brenda Coley and Kirsten Shead are on the same wavelength. Equally outspoken and mutually admiring, they regularly finish each other’s sentences. In fact, I’m not sure that I’ve ever talked with two colleagues who are so totally in-sync. And nowhere is this mind-meld more needed than in Milwaukee — one of the country’s most deeply segregated cities.

Together, Brenda and Kirsten co-lead Milwaukee Water Commons, an organization seeking to repair Milwaukee residents’ relationship with water. But perhaps more importantly, they are turning the status quo on its head and driving a city-wide conversation about what environmental conservation should look like, who should have a voice, and how decisions should be made.

Kirsten: “I think part of what makes our co-executive model unique, besides just really liking each other and working well together, is that it is collaborative at its core. It’s not you take this and I’ll take that…”

Brenda: “…or I’m in charge of this. You’re in charge of that…”

Kirsten: “…We really feel like part of what we’re doing is modeling, in a hyper-segregated city, Black and white leadership. We’re modeling what women-centric leadership looks like. And many of our programs have co-leaders. So that idea of collaboration is everywhere — that any one person or any one culture is not going to be able to solve these problems…”

Brenda: “…that if we’re going to really steward this resource for generations to come, we must build something together. That’s what’s going to be sustainable.”

See what I mean?

Water is literally everywhere you look in Milwaukee — Lake Michigan rests to the east, and the Milwaukee, Menominee, and Kinnickinnic rivers run right down the center. Yet Black Milwaukeeans have historically not been able to enjoy the benefits of these natural treasures due to policies and practices that create and maintain racial inequities.

Redlining — the racist practice of denying People of Color equal lending and housing opportunities — is to blame. Because Black families were intentionally prevented from buying high-quality houses in desirable neighborhoods, families were less able to pass down wealth through the generations. Pile on an influx of Black migrants in the 1960s and the fact that Black voices have been systemically sidelined from power and you are left with a chasm between Black neighborhoods and white neighborhoods that persists to this day. Black neighborhoods like those on the city’s north side are poorer, have fewer parks, and less access to nature. White neighborhoods are wealthier and closer to the lake.

This disenfranchisement carries a dangerous legacy: Around the country aging cities like Milwaukee are facing an infrastructure crisis. The American Society of Civil Engineers gave water infrastructure in the United States a C- grade. Communities of Color are ground zero due to a woeful lack of investment. That is doubly true in Milwaukee, which also faces an unseen emergency: lead piping. More than 40 percent of households in the city — over 66,000 homes — have lead water pipes. Lead poisoning causes kidney and brain damage and harms children’s nervous systems. More than 70,000 laterals in Milwaukee need to be replaced, and the vast majority of those are in Black and brown neighborhoods. “They are bringing the risk of tainted lead into people’s homes,” Brenda says.

The city has been slowly replacing its lead lateral lines, but on the current trajectory, a child born today could be 70 years old before their home’s line is updated. Thankfully, Wisconsin received $79 million through the bipartisan infrastructure bill, and a large portion of that money will go toward helping Milwaukee replace lead pipes. But the investment is just a start. In 2021, the city estimated that replacing every Milwaukee lead lateral would cost about $800 million.

Milwaukee Water Commons is working with state and local governmental agencies, and institutions to build urgency around the problem. The organization is also helping local people understand the dangers of lead in water and giving them the tools to advocate for change.

Kirsten warns against box checking, though: “We have to engage communities earlier and in a more authentic way, so that we don’t go all the way down the path of a solution that’s disconnected from the lived experience.”

Innovation at the grassroots

Honoring and centering lived experience is a key tenet of the cultural shift Milwaukee Water Commons is trying to spur. The bottom line is this: To create positive, lasting change, the people who live near, rely on, and are impacted by the health of their water must have a firm role in crafting the solutions. Historically, though, government and the environmental community haven’t made space for local people — particularly People of Color — in decision-making process.

Brenda: “[Government and] big greens know that the problem is happening — they know there’s lead in the water. But they don’t know how the problem really sits on people. Engaging the community is not just the right thing to do, it’s the necessary thing to do because really that’s where the innovation is. If we want to find out how to solve our issues and our problems, we need to be talking with people.”

Kirsten: “We need to be asking, ‘What is the lived experience of people navigating basement flooding in Milwaukee? We need to hear that at the beginning and have a community-informed vision that is much more grounded in people’s experience.”

The same people who are most impacted need access to power and to spaces where their voices can be heard. Brenda is careful to point out, though, that the process is more involved than just gathering people in a room. “We can’t just convene a meeting about something super wonky and say to community members, ‘What do you think?’ They won’t be able to respond. To me, we’re talking about informed decision-making. We’re getting paid to do this work, but we need to check in with the community and find out if this is the right way to go. Sometimes that means we need to lay out the issue and giving them the information so they can make the decision.”

So, what does community engagement look like in practice?

A safer lake for Milwaukeeans

During the pandemic, when everyone just needed a break — to get into fresh air — Milwaukeeans flocked to Lake Michigan to lounge on its sandy beaches and wade in its chilly waters. There were no lifeguards. But the lake looked smooth. It looked like fun. Black residents who had long been disconnected or made to feel unwelcome at the lakefront had never been given information about how to enjoy their lake — and its currents — safely. And the results were disastrous. Four Black men died in separate drowning incidents. Most were trying to save children.

Nationally, Black people are far more likely to drown than white people. The fact that Milwaukee’s Black community lacks access to safe recreation on Lake Michigan doesn’t help.

“I mean, Milwaukee is a city on the water,” Kirsten says. “But you can live less than a mile from Lake Michigan and have never seen it. And if you do get there, if you’re hyper policed or you’ve never experienced swimming, you’re more likely to experience a drowning.”

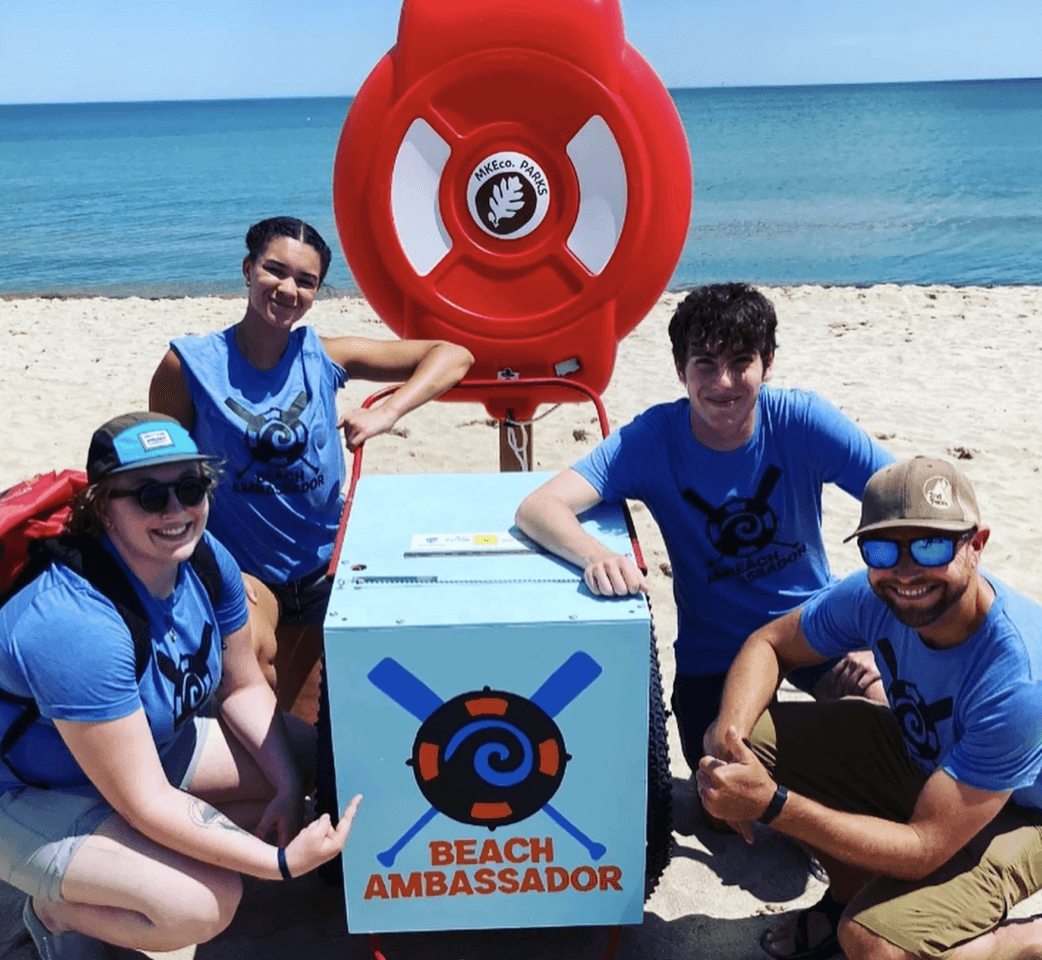

Milwaukee Water Commons recognized the problem and swung into action, forming a “beach-ambassador” program in which young People of Color interact with folks on the beach, educating them about rip tides, currents, and where it’s safe to swim and where it’s not.

“The question was,” Kirsten says, “can we get this knowledge into community hands so that people can make informed decisions? It’s not our job to keep people in or out of the water, but if we give them the information, they can make a more informed decision and can be safer.”

Not only has the program increased awareness about water safety, but also community members are leading the charge on a solution that has legs. Meanwhile, the municipal government is still deciding what to do.

“We’re changing culture around water,” Brenda says, “making sure that people understand that we all belong here. So, we shouldn’t get funny looks when we’re down at the lake. This is all our water.”

Inspiring urban water leaders

Perhaps one of Milwaukee Water Commons’ most successful programs melds education, community engagement, recreation, and celebration. During its summer Water School, the organization hosts teams of adults from other nonprofits, churches, and community-based organizations. One day every month, the teams gather in a different part of their watershed to kayak, swim, fish, and learn about water-related issues. What is their water footprint? How do watersheds work? What are the issues affecting in Milwaukee? How are decisions made around them?

“We’re working with people who don’t normally have these experiences — and connecting folks with the beauty of the river,” Brenda says. “We bring in native folks and Latino folks and Black folks into spaces that are traditionally very white. At first, it’s a little awkward for them, but after a minute or so, everyone’s transformed and happy.”

The program includes a leadership development component that has birthed some of the cities strongest water leaders. Local people who have participated in the program now sit on community advisory committees. They have testified at state discussions around drinking-water access. And many have infused water into work they were already leading.

It’s a model for how to spread information, empower local advocacy, and shift the culture of water and rivers. The community is taking notice, says Kirsten: “Our rivers are really being celebrated more and more in Milwaukee. And more people are making the connection that these spaces are our spaces.”

Solidarity is the future

Enormously effective local organizations, like Milwaukee Water Commons, are working in communities around the country. They are protecting rivers, making rural and urban waterways healthier, connecting more people to nature, and advocating for better practices with how decisions are made around water and our environment.

National groups like American Rivers can play an important role in supporting and advancing their work. We can be strong allies for local groups — particularly those led by People of Color — by addressing power inequities sharing access to decision-making spaces. We can make introductions to people and foundations who can fund their work, and we can pull community-based organizations into discussions they might not otherwise be in. It’s a symbiotic relationship. Because relationships with community-led organizations are absolutely essential for national environmental nonprofits to advance programs on the ground — and to achieve meaningful national policy wins. Local groups act as a bridge to communities, helping build trust and inform the conservation work and priorities of groups like American Rivers.

“If I look at what American Rivers has done for Milwaukee Water Commons, in many ways, they put us on the national scene by introducing us to funders,” Kirsten says. “And then, of course our work spoke for itself. American Rivers recognized the quality and the scope of the work that we do, and really playing a role to transform the movement as we transform our own organization.”

Looking ahead

Nearly everyone in our country lives within a mile of a river but few know what that river provides. Much of our drinking water comes directly from rivers, and clean water is essential to our health. Natural river habitats support thousands of plant and animal species. Our crops and cities alike depend on abundant river water for growth. For many of us, rivers offer recreation and a way to connect to nature. For others of us, our rivers have been sources of pain, sickness, and struggle — or we didn’t even know they were there.

American Rivers believes healthy rivers are for everyone, not just a privileged few. We will not achieve our mission until we dismantle policies that allow damaged, polluted rivers to flow through Communities of Color, while more affluent — often white — communities enjoy cleaner, healthier rivers.

The way forward must be rooted in collaboration. It must include greater partnerships between organizations like American Rivers and Milwaukee Water Commons and deeper engagement with communities that deal with river and water issues every day. Together with advocates like Brenda and Kirsten, we can champion a movement to improve the health of communities and their water. Because at the end of the day, that is our best hope to equitably provide the benefits of healthy rivers and clean water to everyone.

Learn more about Milwaukee Water Commons’ work at www.MilwaukeeWaterCommons.org.

In the remaining days of 2022, we’re happy to share some important wins for rivers – including funding for critical clean water and river restoration programs, as well as new Wild and Scenic River designations. While there’s much to be thankful for, the bill still has a number of shortcomings. In this blog, we break down the funding and policy highlights.

On December 20, appropriators released the highly anticipated fiscal year 2023 omnibus spending package which includes modest environmental and conservation funding increases. Overall, the bill would fund the government at $1.7 trillion for most of 2023 – $858 billion toward defense and $772.5 billion in domestic spending.

The omnibus spending bill funds federal agencies such as the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) and Department of Interior (DOI). The EPA received a $576 million increase from current levels to support the agency’s science, environmental, and enforcement work. The bill also includes $14.7 billion for DOI programs, an increase of $574 million above fiscal year 2022.

These funding increases support river restoration and river health goals across the country.

Key Takeaways From The Omnibus Spending Package:

- General increases to EPA, DOI, and National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration

- Additional supplemental funding for National Park Service to restore 500 of the 3,000 staff positions that have been lost over the past decade

- $40 billion for disaster recovery and drought

- $600 million to address water issues in Jackson, Mississippi.

- $682 million for EPA’s geographic program including $92 million for Chesapeake Bay Program and $368 million for the Great Lakes Restoration Initiative

- $1.67 billion for EPA’s Clean and Drinking Water State Revolving Funds

- $50 million for EPA’s Sewer Overflow & Stormwater Reuse Municipal Grant program

- $65 million for Bureau of Reclamation’s WaterSMART grants

Key River Budget Priorities & Performance:

| Agency | Program | FY 23 Rec. from American Rivers | Omnibus Spending bill 12/20/22 | About the Program |

| EPA | Reducing Lead in Drinking Water | $100M | $25M | Reduces the concentration of lead in drinking water. |

| EPA | Sewer Overflow and Stormwater Reuse Municipal Grants Program | $280M | $50M | Manages combined sewer overflows, sanitary sewer overflows, and stormwater flows. |

| USBR | Dam Safety Program | $200M | $210.2M | Ensures Reclamation dams do not present unreasonable risk |

| USBR | Klamath Project | $25M | $34.8M | Provides funding to improve water supplies in the Klamath River Basin. |

| USBR | Lower CO Operations Program | $45M | $46.8M | Implements the Drought Contingency Plan and the Lower Colorado Multi-species Conservation Program. |

| USBR | Yakima River Basin Water Enhancement Project | $30M | $50.3M | Enhances streamflows and fish passage for anadromous fish in the Yakima River Basin. |

| Corps | Upper MS River Restoration | $55M | $55M | Ensures the viability and vitality of Upper Mississippi River fish and wildlife. |

| Corps | Engineering with Nature | $12.5M | $20M | Aligns natural & engineering processes to deliver economic, environmental, and social benefits |

| FEMA | Floodplain Mgmt. & Mapping | $200M | $206M | Improves floodplain management, develops flood hazard zone maps, and educates on the risk of floods |

| FEMA | National Dam Safety Program | $92M | $9.65M | Reduces the risks to human life, property, and the environment from dam related hazards. |

Policy Wins for Wild and Scenic Rivers, Western Water

In addition to the funding noted above, American Rivers is very pleased to share that key provisions supporting river restoration are advancing. We applaud the hard work championed by Senators Richard Shelby (R-AL) and Patrick Leahy (D-VT) and many others on the Hill to make this omnibus spending bill a bipartisan effort. Though we are disheartened that we didn’t get to see the bipartisan, bicameral public lands and water package, we can celebrate two new Wild and Scenic River designations: the York River in Maine and Housatonic River in Connecticut. Together these bills would designate more than 70 river miles. Two Wild and Scenic River studies from Florida were also added.

Several western water bills made it into the omnibus spending bill which will improve drought resilience, boost water supply, and support wetland conservation. For example, the Colorado River Basin Conservation Act (S. 4579/H.R. 9173) would allow DOI to continue to partner with Upper and Lower Basin states alike, to keep more water in the Colorado River and its reservoirs, by incentivizing voluntary water conservation projects at the user level.

Shortcomings in the Omnibus Spending Bill

The omnibus spending bill falls short of meeting bold river health goals that are grounded in advancing scientific efforts, supporting enforcement, and directing growth in river communities that could have benefited from additional funding. While we noticed gains in WaterSMART, Dam Safety Program, Yakima, and Klamath Projects under Bureau of Reclamation, American Rivers noted less than optimal funding levels for the Central Valley Project Restoration Fund in California and the Columbia and Snake River Salmon Recovery Project in the Pacific Northwest.

The Army Corps of Engineers programs such as Engineering with Nature, Floodplain Management Services, Sustainable Rivers Program, and the Upper Mississippi River Restoration programs did not suffer significant cuts. Nor did NOAA programs specifically Pacific Coastal Salmon Recovery Fund. However, we acknowledge small reductions in funding to the Flood Hazard Mapping and Risk Analysis Program (RiskMAP).

Another item American Rivers noticed is large money carve outs for “Community Project Funding Items” also known as earmarks. When taken out of the Clean Water and Drinking Water State Revolving Fund (SRFs) capitalization grants, it leaves the EPA programs with less than half of what these programs received in Fiscal Year 2021. The long-term viability of the SRFs is in question and American Rivers will work hard to ensure its success in future years so high-priority projects are not delayed or increase the risk to public health and the environment.

We’re disappointed the sweeping omnibus legislation did not boost more funding to protection, restoration, and enhancement of fish and wildlife, but are hopeful that the focus in drought resilience in the Southwest, water infrastructure in Jackson, Mississippi, as well as modest increases to Corps, DOI, NOAA and EPA programs will continue to place a focus on water quality and quantity.

With the Spending Outline, What’s Next?

The Senate took the first step with a procedural vote on the omnibus Tuesday. The House is expected to vote on the bill on Friday, Dec. 23rd, 2022. Despite some missed opportunities, this bill has something for everyone. American Rivers encourages the House and Senate to move swiftly to secure the passage of this bill. We expect the omnibus spending bill to have enough support to get it to the President’s desk before the Friday night deadline when the Continuing Resolution expires.

Someone asked me the other day if I knew where I got my water, and to be honest, I had no idea. Like any other person, I consulted Google. I am going to make the assumption that you might not know where your water comes from either. So I took the liberty upon myself to find out for you!

Being from Seattle, I just assumed it came from the wonderful Mt. Rainier but it turns out it comes from the Cedar River, which I have spent plenty of time on as a kid and for field trips, as well as the Tolt. If you are also from Seattle, you know our water tastes the best.

Now that we have established where my hometown gets its drinking water from, let’s check out where other major cities across the United States get theirs.

Going all the way to the east coast, New York City gets its water from the Delaware River basin.

A majority of metro Atalnta gets its water from the Flint and Chattahoochee rivers. Fun Fact: The Flint river originated directly under the largest and most trafficked airport in the USA, the Atlanta Airport.

The Colorado River, gives drinking water to 36 million people in 7 states from Denver, Phoenix, Las Vegas, and all the way to Los Angeles. The Colorado River runs through the Grand Canyon, which is currently at risk of running dry, meaning the Colorado River itself is at risk. For more information on this ever-changing and seemingly worsening river, read here.

The residents of our nation’s capital, Washington D.C., (where important decisions are being made right now about our nation’s rivers) get their drinking water from the Potomac River.

American Rivers’ River of the Year, the Neuse River, gives water to over 4 million people in North Carolina all the way from Durham, NC to Hoboken, NC where it enters the Pamlico Sound!

While there is usually no need to worry about the safety of your drinking water since it is regularly tested, some of the rivers people’s water comes from are heavily polluted and for some are at risk of worsening condidtions in the near future. Currently, millions of people in Jackson, Mississippi are without water after recent floods, for more information about this, CLICK HERE.

18 million people from Minneapolis to New Orleans rely on the Mississippi River to supply their water. While not only giving water to 18 million people, it is also vital to the United States in terms of transportation for barges to import and export crucial commodities such as soybeans and corn.

While many don’t have to worry about what comes out of their faucet, there are still millions without access to clean drinking water. Next time you are swimming or fishing in your local river, just keep in the front of your mind that it could possibly be providing water to millions of people.

On December 15th, 2022, the Senate voted to pass the National Defense Authorization Act in which the Water Resources Development Act of 2022 (WRDA 2022) is included. It was passed by a vote of 83-11. Last week, the House passed the bill on December 8th with an overwhelming majority of 350-80. It will now go to President Biden’s desk for signing into law.

This is the largest Water Resources Development Act (WRDA) in history and comes in at a time when our nation needs it most. The bill provides authorization for the Army Corps of Engineers to carry out water resources infrastructure projects to address flooding, waterway transportation, and ecosystem restoration. Importantly, this bill includes provisions to support Tribal and underserved communities, and address climate change.

American Rivers has worked with Congress to include provisions to protect and restore our nation’s rivers and floodplains. Below are some of the key provisions that we are most excited about.

Sections 8111. Tribal Partnership Program; 8112. Tribal Liaison; 8113. Tribal Assistance; 8114. Cost sharing provisions for the territories and Indian Tribes; and 8115. Tribal and Economically Disadvantaged Communities Advisory Committee are valuable provisions. We support these efforts to improve outreach to, and engagement with, these communities and give them a seat at the table. We are also pleased to see the initiative to build out the Corps of Engineers workforce through outreach in schools, colleges, and universities with a prioritization of recruiting from economically disadvantaged communities. We believe these steps will serve both the Corps and the communities well.

With climate change impacting the nation, promoting nature-based approaches on a project and watershed level scale is imperative to adapt to increasing floods and water scarcity. WRDA 2022 includes several provisions that will help promote the use of nature-based approaches and better serve and protect our communities while promoting ecosystem resilience through more responsible levee management and floodplain restoration.

Section 8103 – Shoreline and riverbank protection and restoration mission calls for restoring the natural functions and values of rivers and shorelines throughout the United States. Section 8121– Assessment of Corps of Engineers levees, will assess for opportunities for modification of levees, including for restoring connections with adjacent floodplains. American Rivers also worked to include language for the Corps to identify floodplain reconnection opportunities on federal lands. While this provision was not included in the final bill, we will work with the Corps to support sections 8103 and 8121, while continuing to work on getting additional federal levees assessed.

American Rivers worked diligently with our partners at American Whitewater and the Theodore Roosevelt Conservation Partnership to include section 8122- National Low-Head Dam Inventory. This inventory will contribute significantly to public safety as low-head dams are known public safety hazards, and yet not inventoried nationally, and making this information publicly available will help river users identify life-threatening low-head dams. We also hope that this inventory will help the public identify obsolete structures that continue to pose a safety hazard and would be suitable for removal. In areas where dam removal is not an option, we support additional funding to go towards grants for signage and public education about low-head dams

Section 8123– Expediting hydropower at Corps of Engineers facilities, allows for retrofitting Corps dams with hydropower. We support this provision with the understanding that the structures in question are already serving their legislatively authorized purpose and will continue to do so for the foreseeable future. Recognizing that retrofitting a non-powered Corps dam with hydropower is not always feasible, we will continue to advocate for the diligent assessment of these projects and their use to determine if they would better serve the taxpayers, community, and local ecosystem by being disposed of instead of extending their life solely for non-power purposes.

The consideration of reforestation in section 8137 is an exciting and forward-thinking provision that encourages measures to restore swamps and other wetland forests in studies for water resources development projects. This is another important step towards focusing on ecosystem restoration. The benefits of flood control and water quality improvements that come from healthy swamps and wetlands are incalculable.

There are several provisions related to river restoration and protection and better river management, including section 8144 – Chattahoochee River Program, section 8145 – Lower Mississippi River Basin demonstration program, and section 8219 – Hydraulic evaluation of Upper Mississippi River and Illinois River. The Chattahoochee River program will provide assistance to non-federal interests for water-related resource protection and restoration projects affecting the Chattahoochee River Basin. The Lower Mississippi program will provide assistance to non-federal interests for projects focused on flood or coastal storm risk management or aquatic ecosystem restoration. The hydraulic evaluation of the Upper Mississippi River and Illinois River basins will provide studies on the flows for rivers in the upper basin, which we hope will contribute to more effective management and restoration plans.

The Government Accountability Office (GAO) studies authorized in section 8236 are encouraging, especially the review of mitigation projects and the evaluation of their performance. These studies will require a report on the results of projects and activities to mitigate fish and wildlife losses that occurred as a result of a water resources development project. Within this section, we also support the study on the integration of information into the national levee database as this information is essential to the management and improvement of our nation’s levees.

We are pleased to see section 8140 – Policy and technical standards directing the Secretary to update the agency standards. With this update, the Corps will have to include climate change and nature-based solutions in their practices. We look forward to the report on the Corps of Engineers reservoirs under section 8153 so that Congress may further evaluate the operation, utility, and future of these reservoirs.

Overall, we applaud the safety and environmental provisions in this bill and the passing of this paramount piece of legislation to protect our natural and engineered water infrastructure and the people that rely on it.

Section by section summary can be found here and the full WRDA bill can be found here.

This blog was written by Katie Schmidt. Jaime Sigaran, Ted Illston, Brian Graber, and Eileen Shader

Alarm bells are ringing on rivers across our country. The Mississippi River hit record low water levels after months of drought and snarling barge traffic, threatening drinking water supplies. The Colorado River is in dire condition, with shrinking reservoirs threatening a $1.4 trillion economy. Nationwide, communities, businesses, and local economies are feeling the impacts of increased droughts and floods on their own hometown rivers.

It’s also of grave concern that we are losing nature: freshwater species are going extinct at twice the rate of terrestrial or marine species. From wild salmon in the Pacific Northwest to hundreds of species of amphibians, our country’s web of life is at risk as river habitat is threatened.

Perhaps the greatest threat is lack of awareness of how important rivers are to our lives. Rivers provide clean drinking water for most of our communities. River recreation and restoration are key drivers to a strong economy, generating $862 billion in economic output and supporting 4.5 million jobs — especially important during uncertain times and inflation.

By protecting rivers, we stem the loss of nature and buffer the effects of climate change by reducing flooding and providing more consistent water flow in times of drought. Protecting rivers isn’t a luxury, it’s essential to our health, our economy, and the future of our country. Right now, Congress has an opportunity in the lame duck session to advance powerful bipartisan river protections in a public lands and waters omnibus bill.

American Rivers is asking Congress to pass a land and water protection package that includes new Wild and Scenic River and public lands protections for rivers pending in Congress that would conserve rivers in seven states, from Maine to Oregon. These bills would protect the free and natural flow of these rivers and their special values, such as clean water, transportation, recreation scenery, fisheries, and culture. Once passed into law, the legislation currently pending in Congress will expand durable, community-supported protection for rivers.

At a minimum there are nine river conservation bills, in five states that Congress should enact into law that have either passed out of the Senate Energy and Natural Resources Committee or the U.S. House with bi-partisan support; the typical standard of legislative viability. These bills are a reflection of homegrown initiatives originating in mostly rural communities.

Some examples include the Gila River in Southwest New Mexico with its amazing canyons, rock formations, rare Gila trout, and rare wildlife habitat. The local Grant County Commission and businesses in this heavily mining dependent region, support protecting the lifeblood of the community.

The Oregon Recreation Enhancement Act would establish a new National Recreation Area for the economically important and salmon-filled Rogue River and codify an existing 20-year administrative mineral withdrawal in the area supported by Curry County; typically one of the most conservative in the state.

The Kissimmee River Wild and Scenic River Study Act would explore protection for 103 river miles of this extraordinary river in Florida, building on the historic restoration of the Everglades.

In Maine, the York River Wild and Scenic Rivers Act, sponsored by Sen. Angus King and Sen. Susan Collins, would protect more than 30 river miles.

Rivers and streams are our nation’s circulatory system, like the veins and arteries in our own bodies. We must keep them clean and flowing to protect our health, our economy, and our communities. By protecting these rivers, we will help preserve their clean water, nature, and sacred values for future generations. Congress should seize this critical moment to advance bipartisan protections for the rivers on which all life depends.