Song in Sacred Canyons: Indigenous Youth and the Future of Our Rivers

Guest blog by 2025 Southwest Emerging Artist Scholar; American Rivers Southwest River Protection Program and the FreeFlow Institute

The canyon was a sanctuary of morning shade as we spread out across the natural sandstone benches. The rocks around us mirror the color of our own skin—an intergenerational group of youth and elders nestled in for reverence. The silence before our prayer began was accompanied only by the steady trickle of the creek, a melody to the distant waterfall. The gourds rattled to a familiar beat, and our voices followed the tempo. Eyes closed, smelling the scent of burning tobacco. The harmony of voices, singing in unison, the appreciation for water, for the river.

Months passed after that morning, and I sat in a forest of ponderosa on the rim of that same sacred canyon. I sit pondering how the stream-carved chasm sounds today. It’s absent our singing voices, although our blessings remain in the spirit of that place. Drifting away from the daydream, I’m filled with contentment knowing that the medicine created, shared, and received lives on with the Native youth who sang with me that day.

I live, work, and play across the Colorado Plateau, committing most of my time to engaging with Native youth in outdoor spaces. I build community with Native youth on traditional farms across the Navajo Nation, in deep canyons and forests, and on all the mesas in between. Indigenous youth are our future—a proclamation that became abundantly clear this year as I facilitated culturally relevant outdoor education programs with various nonprofits in the Four Corners region. This level of community engagement in relation to the land represents movement toward the protection of biocultural diversity. Through generations of caretaking, the land of Indigenous peoples has maintained immeasurable biodiversity. The degree of protection and caretaking is evolving in challenge and intensity due to the unfortunate reality that Native communities are disproportionately affected by the severe impacts of climate change. The consequences of climate catastrophe will be left in the hands of Indigenous youth. So how do we inspire them to play a part in the story they are woven into?

Let's stay in touch!

We’re hard at work in the Southwest for rivers and clean water. Sign up to get the most important news affecting your water and rivers delivered right to your inbox.

It begins with reminding youth that they hold an intrinsic connection to the land. One of the many lasting tactics of colonialism is the forced disconnection of Native peoples from the land. Decades of violent removal, boarding school, and dispossession of land and water have left generations of youth to feel they don’t belong to the land the way their ancestors did. This lack of belonging is exacerbated by the gatekeeping of outdoor spaces by white communities. Socially discouraged accessibility to the outdoors is a barrier to maintaining cultural connection to place.

Growing up in the storied land of the Northern Arizona desert, I began shaping my personal relationship to land at a very young age. My time in red sand and between canyon walls was enriched by the teachings of my family, of my Diné community, that we are a part of this land. While I was never involved in an outdoor youth program, my proclivity for facilitating such programs stems from my belief that Indigenous youth should have limitless opportunity to design an intentional relationship to land and water based on their cultural and personal values.

This year, I had the privilege of helping to facilitate the annual RIISE (Regional Intertribal Intergenerational Stewardship Expedition) trip through the Grand Canyon Trust. Indigenous youth and elders gathered to share prayer, tradition, and abundant laughter along the Colorado River. On this trip, we honored the fact that spirit, knowledge, and tradition live in a physical space, brought to life by the stories told and prayers sung. To pass on teachings, Native youth must have access to these places. I’ve shared space and time with over a hundred Indigenous youth this year, and a resounding theme among all of them is a deep desire to know their culture by personally experiencing the land their relatives knew so intimately.

The relationship they desire has been taken away from them by the settler-colonial state we live in, which exploits racial identities to gain economic capital. National Parks are an example of this racial exploitation: land dispossessed from Native peoples has been turned into a commercialized and profitable space. Outdoor recreation is a predominantly white space, a privilege to those who can afford and feel safe in such environments. Outdoor recreation spaces are curated for the white experience, therefore becoming inherently exclusive. Native youth rarely see people of their own cultural background or race represented in the outdoor industry, thus perpetuating the false narrative that they don’t belong.

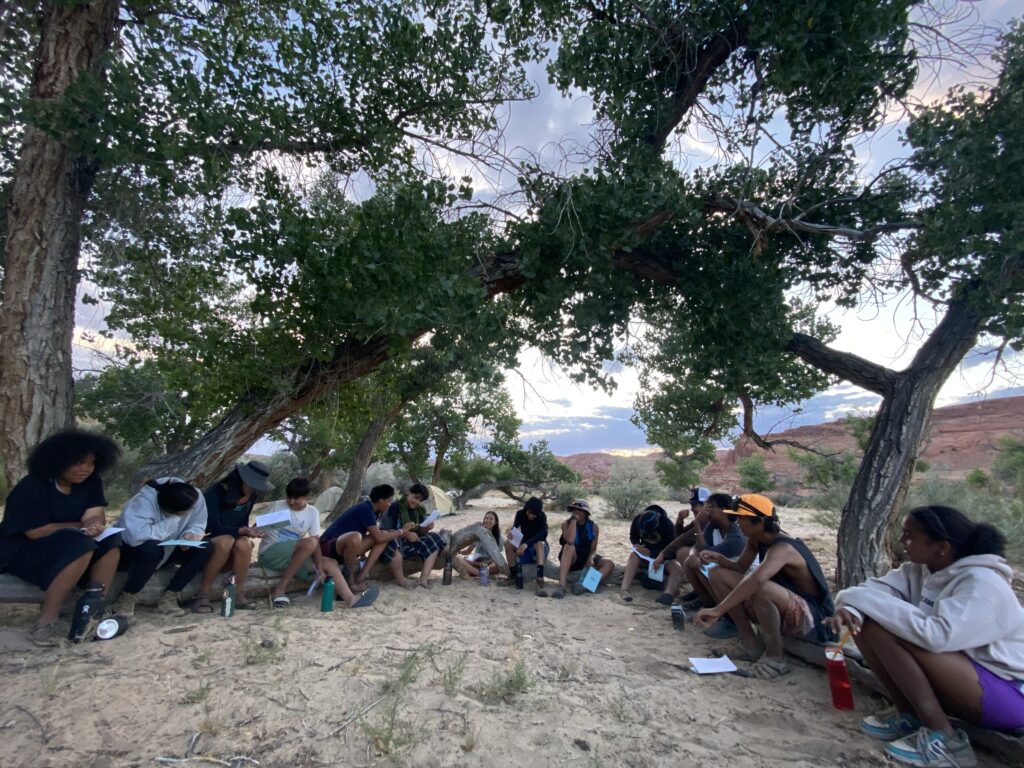

Providing a safe learning space for Black and Brown youth outdoors is a revolutionary act that uplifts both the individual and the community. Time on the land, in community, ignites a sense of belonging; an opportunity to heal the youths’ relationship with land. I observe this phenomenon when facilitating Native Teen Guide in Training trips through the Canyonlands Field Institute on the San Juan River each summer.

We walk alongside sandstone walls that tell of migration in the river corridor from millennia ago. The tradition continues as the youth paddle down the river. This river trip is the first and potentially only time many of these youth will have access to experiential learning and cross-cultural exchange in an outdoor recreation space. The riotous laughter of the youth ricochets across the water as we spend days passing by boats of people who don’t look like us. Some youth notice; others are blissfully oblivious to the racial disparity on display on their ancestral river. Despite these observations, we find our belonging in the stories of our people that etch themselves into the rocks, plants, and animals. Our night air is filled with a steady drum as we round dance, our hands interlaced, feet shuffling in red sand, an offering to the stars.

Outdoor programs geared toward Native youth have an impact that shouldn’t be limited to a singular experience. The magnitude of a culturally-relevant trip is, in essence, a reclamation of a relationship to land and water. How do we ensure the continuous growth of this relationship? We continue to provide Native youth with the opportunity to learn and build relationships with the land and water—to know the river and land as beings with a spirit, as relatives. We help them cultivate an inclination to care for such relatives. By instilling the traditional belief that our lineage is rooted in the land and the water, we can help create a generation of protectors. People protect what they know; they protect who they care about.

Encouraging the changemakers of the future does not eliminate the feeling of helplessness regarding the water and climate crisis in the Southwest and around the world. On a sunbaked afternoon, bellies full and lungs worked from hours of games at Redwall cavern—in Marble Canyon on the RIISE trip this past summer—the Native youth settled in for a floating talk. They sank into their seats on the rafts, all tied together for the moment, allowing the serenity of the walls to add a dramatic effect for our discussion of water in the West.

Complex topics like water law, legislation, and litigation—and related and problematic jargon, too—hindered a complete understanding of Western water among the youth. A discussion like this can have a similar effect on adults. Worried that we were losing their attention, my mind raced with ideas on how we, as facilitators of the discussion, might connect this topic to their lives, personally. Thinking on my feet, I reminded them of culture: of the days we had already spent giving offerings and blessings to the land and water, learning and strengthening our bond to the sacred. This is specialized knowledge, I told them truthfully.

“There are people in windowless rooms making decisions about a river they may have never floated on, bathed in, or prayed to. Despite this, you cannot forget the generations of wisdom passed through this place, through you, that instructs accountability as land and water protectors.” This dynamic connection to ancestral homelands is what sets Native youth apart; it is their superpower against a world committed to poisoning the earth.

Indigenous youth play a critical role in the unfolding story of our planet. They, too, hold wisdom. The significance of intergenerational knowledge exchange becomes especially evident when in the presence of Native youth. One teaching I received from their enlightened youthfulness is the seamless transition between prayer and play. After an hour-long ceremony at each stop in the Grand Canyon, play promptly ensued. It is a teaching applicable to anyone living in this time, an honoring of the dualities omnipresent in the Indigenous experience. The youth raised my belief that there is room for reverence and laughter in sacred spaces. Our presence throughout the Canyon was marked by steadfast joy: joy for the chance to be in community, to reinhabit the spaces of our ancestors. In this way, joy was our act of resistance.

It’s midday at Whitmore Panel in Grand Canyon (If you know this place, you know scorching heat). We gathered around three young Zuni wisdom holders. We stood, backs of legs burning, listening to the youth sing us into the place in a good way. Taking in the stories on the wall, one of the Zuni youth recognized a symbol. The same symbol he paints on his traditional pottery. Thousands of years between him and his ancestors disappeared at that moment, a lineage connection so profound it forced all of us to recognize the depth of our presence. The presence of Native youth on sacred land is essential for the continuation of culture and the envisioning of the future.

Resistance to the exclusionary character of outdoor recreation is reconnecting Native youth to their right to access their ancestral homelands. Inclusivity begins with acknowledging the barriers to access and understanding how these barriers are a result of systemic oppression. Following this acknowledgment comes owning the part we each play in upholding these systems. Ultimately, this privilege can be leveraged to support Native youth outdoor programs. These programs are gaining traction as we collectively work toward Indigenizing the future. This future honors Indigenous lifeways and values like reciprocity, care, and relationship building. You can be a part of the movement by supporting organizations like these:

- Rising Leaders—Grand Canyon Trust

- Native Teen Guide In Training—Canyonland Field Institute

- Paddle Tribal Waters—Rios to Rivers

- River Newe

- Pandion Institute

- Pollen Circles

You can amplify your support by advocating, donating, and building relationships with your local Native youth programs and community.

Guest contributor Chyenne (she/they) is a Diné adzaani from the small desert town of Page, AZ. The sandstone mesas, canyons, and sagebrush-painted plateaus became her teachers, instilling her creative capacities. Today, Chyenne works and writes as a dedicated land and water protector, applying her lessons from her homeland alongside a MA in Indigenous Studies and BA in Social Justice and Environmental Studies from Prescott College in her work with various non-profits in the Four Corners region.

1 response to “Song in Sacred Canyons: Indigenous Youth and the Future of Our Rivers”

A remarkable story that inspires me to think about the past and its impacts on the present. In a time when we can’t even decide what it means to be American, the Native Americans press forward with time-tested Truths and beliefs that have kept them united through the worst of days. I value the efforts of these extraordinary people who refuse to believe their destinies are already written. If only we all could see the world this way.