Colorado River in the Grand Canyon

The Colorado River’s Grand Canyon is one of our nation’s, and the world’s, greatest natural treasures. A sacred place of deep cultural significance, it is also a beloved recreation and travel destination, and home to a wide diversity of wildlife. But rising temperatures and severe drought driven by climate change, combined with outdated river management and overallocation of limited water supplies put this iconic river at serious risk. As critical decisions about water management along the Colorado River are made, the Bureau of Reclamation and the seven Colorado Basin states must consider the environment a key component of human health and public safety and prioritize the ecological health of the Grand Canyon.

The Colorado River flows nearly 1500 miles from the Rocky Mountains to the sea in Mexico. Along its way, the river traverses some of the driest and hottest areas of the country, providing drinking water to 40 million people, including some of the nation’s largest cities like Los Angeles, Phoenix, Las Vegas, and Denver, as well as 30 federally recognized Tribes.

The Grand Canyon is the iconic heart of the Colorado River. This 277-mile stretch of river in Northern Arizona is unmatched in nature. Recognized as a World Heritage Site, one of the Seven Natural Wonders of the World, and one of the most famous landscapes on earth, the Grand Canyon is the foundation of the Colorado River Basin’s natural and cultural fabric, and the National Park draws millions of visitors each year.

It is the lifeline between the Upper and Lower Colorado River Basins and is bookended from above and below by two massive dams, forming the two largest reservoirs in the country. Grand Canyon National Park starts 16 miles below the tailwaters of Glen Canyon Dam located in Page, Arizona. Construction on the dam was completed in 1963, and waters began to back up behind the dam, flooding the back country of Glen Canyon to create Lake Powell. Hoover Dam in Nevada was completed in 1936 and backs up water to form Lake Mead – the largest reservoir in the US – backing up the river 65 miles at its longest reach to Pearce Ferry at the western end of Grand Canyon.

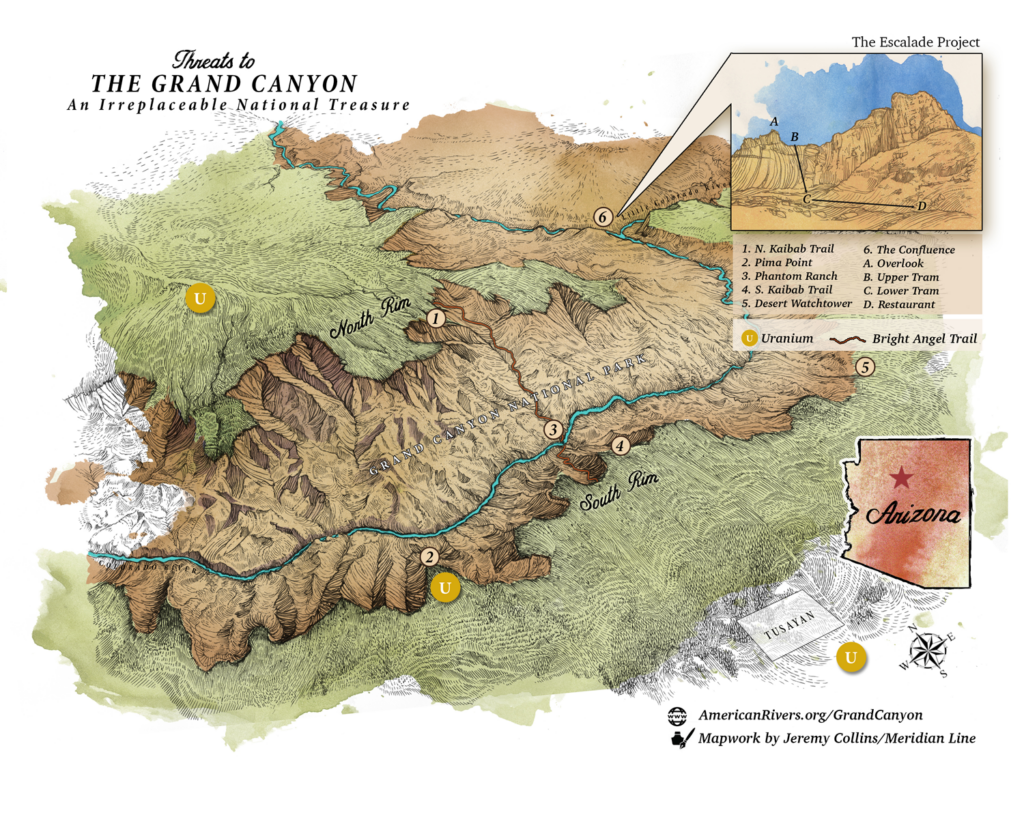

Threats to this Iconic Landscape

The Colorado River is on the brink of collapse, and the Grand Canyon is in the crosshairs as river managers make critical decisions about how to allocate dwindling water supplies. While the River originally terminated in Mexico’s Sea of Cortez, it has been so over-tapped since the mid 1900s that it dries up 100 miles from its original end point. Over the past 20+ years, river flows have dropped precipitously, and water levels of Lake Powell and Lake Mead have fallen to historic lows, in large part driven by climate change.

To protect critical infrastructure including dam integrity, hydropower generation and the ability to deliver water through the Grand Canyon to Nevada, Arizona, California and Mexico, the federal government and the 7 basin states must continue to modify the amount and timing of water allowed to flow through Glen Canyon Dam. The question before river managers is ‘will we attempt to solve the basin’s water challenges by sacrificing the health of the Grand Canyon, or will we pursue lasting solutions that balance water demands with environmental health and safety?”’

Let's stay in touch!

We’re hard at work in the Southwest for rivers and clean water. Sign up to get the most important news affecting your water and rivers delivered right to your inbox.

In response to more than two decades of dry years throughout the Colorado River basin, in 2022 the US Bureau of Reclamation (USBR) took emergency actions to protect infrastructure at Lake Powell.

Altering flows from Glen Canyon Dam has significant impacts on the Grand Canyon. The prolonged drought and accelerating impacts from climate change triggering falling lake levels at Lake Powell has already caused significant harm to the canyon. If future flows are severely altered without consideration for the environment, it could further devastate the Grand Canyon’s irreplaceable natural, cultural, and recreational values.

For many, the Grand Canyon and its surroundings are sacred. Reducing releases from the dam to turn the river into a mere trickle would not only impact native fish, plants, and wildlife, but also the health and well-being of those who are inextricably tied to this place. More than a dozen Native American Tribes and Pueblos revere the Canyon, and millions of people a year find awe, healing, and excitement by just being in and around this place. These challenges are serious threats to the health and well-being of both people and the environment, and if not solved, could do serious, lasting harm to arguably the most recognizable National Park in the country, and all people who love it.

Furthermore, with the rapid and consistent decline of water elevations at Lake Powell, Colorado River flows from Glen Canyon dam are warming. That is, the warmer layer of water in the top of the reservoir’s water column has dropped to a level where that warm water is flowing through the dam’s hydropower tubes. This situation has allowed high-risk, non-native fish such as smallmouth bass to pass through the dam into the Grand Canyon. Smallmouth bass are new to the Grand Canyon environment and biologists fear they will cause serious harm to both cold-water sport fish (rainbow and brown trout) and juvenile native and endangered fish such as the humpback chub. Without a mechanism to stop these and other types of non-native fish from getting into the Grand Canyon, cold-water and native fish populations that have been supported through long-term investments of millions of dollars and countless operational hours will once again be placed in serious jeopardy.

We simply cannot allow the beloved Grand Canyon to become an ecological sacrifice zone as we work to solve the Colorado River basin’s ongoing water crisis. The Bureau of Reclamation is currently considering federal actions where the public can participate and encourage the development of flow regimes that will incorporate and consider ways to protect the ecological, cultural, and economic values of the Grand Canyon.